ADHD in the Elementary School Years: Dissecting a Developmental Dilemma

ABSTRACT: The academic, social, and extracurricular challenges of the elementary and middle school years often bring to light a child’s deficits in the areas of attention and self-control.

Such deficits can have a variety of causes, including learning disabilities, emotional disorders, hearing or vision problems, and social stressors—as well as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Of special concern in the digital age is that ADHD can exacerbate the negative consequences of video games, the Internet, and other media.

When attempting to discern the cause of inattention or impulsivity in a specific patient, thorough history taking is crucial. Often, the problem is multifaceted, and a child’s inattention and hyperactivity cannot be explained by a single diagnosis. Numerous psychological conditions are frequent comorbidities of ADHD.

Jimmy, a 12-year-old boy, comes to your office for a well-child visit in November. His mother looks at him disapprovingly, then casts a worried look at you.

“Things are not going so well at school,” she says. “So far, his grades are worse than last year. His teachers say he is always distracted and fidgety at school, and he has trouble staying organized. Even when he does his homework, he forgets to turn it in.”

Jimmy says bluntly that everything is “fine,” but his mother interjects, “He doesn’t have many friends, and all he wants to do is play video games at home. I want to say he may have ADHD, but when I see him focusing on his video games, I don’t know what to think.”

This story is familiar to many pediatric providers. The long list of possible reasons for Jimmy’s difficulties can be overwhelming to sort through in the primary care office.

This article discusses what’s new in the understanding of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), its impact on a child’s health and development across the lifespan, and pointers about how best to help patients like Jimmy.

In the Beginning …

ADHD can begin to cause problems well before a child starts grade school. In its 2011 ADHD clinical practice guideline,1 the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended initiating an evaluation for ADHD in children as young as 4 years old who have symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity in multiple settings. Behavior is an extremely common concern about all children at this age, but it may be the first signal of ADHD for some children.

ADHD in children at this age is not “bad behavior.” In the preschool years, children are actively exploring their world. They develop a strong imagination, a vehicle for playing with other children. Yet they do not fully understand actions and their consequences. A child with ADHD symptoms may be scolded frequently by his or her parents for impulsive behavior, but the child might not possess the expected capacity for self-regulation, nor the understanding of why certain behaviors are “wrong.”

The developmentally appropriate need for attention may perpetuate undesirable behaviors: The child may seek the negative attention he or she is used to getting. In preschool or other structured settings, the child may be so dysregulated or disruptive that he or she has difficulty learning the social and preacademic skills necessary to prepare for kindergarten. The preschool child with ADHD may already have many disadvantages compared with unaffected peers by the time he or she reaches school age.

School’s Demands Reveal Deficits

Children face many developmental challenges as they progress through the elementary school environment. Classroom expectations become increasingly more complex. Children must follow rules, listen to directions, complete tasks, and keep track of their belongings. Cognitively, elementary school students shift from thinking symbolically to reasoning about the “real” world. Counting, matching, and word recognition lay the foundations for higher-order thinking: Math extends into fractions; writing requires topic sentences; and group projects entail prioritizing, coordinating, and cooperating. At approximately 12 years of age, thinking begins to extend beyond the concrete to the abstract.

Socially, children are expected to have an increasingly better understanding of others’ points of view. They learn to interpret nuances in tone of voice and facial expression, to negotiate cliques, and more often than not to cope with bullying at some level. They are expected to find and pursue activities outside of school that interest them while learning to set goals, overcome challenges, and meet expectations in order to improve their skills.

For a child with ADHD, these demands might be too much. A student’s inattentive, hyperactive, and impulsive nature can make complying with the rules of the classroom difficult, resulting in much negative attention. Academic struggles may intensify. Other children may see this negative attention and struggling and may distance themselves socially. Because the child now can intuit others’ point of view, he or she may begin to feel isolated, “stupid,” or unpopular. Moreover, a child with ADHD is more likely to be a victim of bullying in the school setting than an unaffected child.2-4 Problems with self-esteem and mood may arise.

Over time, difficulties accumulate, and a child’s situation may cross the line from minor obstacles in achievement to serious problems in functioning.

Beyond School

We are learning more about how ADHD can impact a person’s life, not only in the present but also in the future. Recent research shows that children with ADHD are at increased risk for poorer academic achievement, grade retention, and school dropout,5 with more subsequent occupational problems.6,7 Children who have ADHD are also more likely to have one or more psychiatric illnesses as adults, including major depression, anxiety, and antisocial behavior. Even graver, these children have a significantly elevated risk of attempting suicide or dying from suicide as adolescents or adults than do those without ADHD.8,9

Researchers have found links between ADHD and a host of conditions, including obesity, injury, sleep problems, and risky sexual behavior.9 ADHD also is an important risk factor for developing substance-use disorders. Children with ADHD are more likely to start smoking tobacco at an earlier age and to use alcohol and other illicit drugs when they are older.

Especially vulnerable to illicit drug dependence, however, are children with ADHD and comorbid conduct disorder, which may arise as a developmental consequence of having ADHD and the downward spiral of poor parental interaction, resistance to education, social and academic failure, and association with negatively influencing peers.9,10

ADHD in the Digital Age

Children today grow up in a world teeming with gadgets and devices. Learning to navigate electronic devices is as natural to children as learning to flip pages in a book. Those with the dysregulation and poor impulse control of ADHD gravitate toward the stimulating world of technology, the impact of which we are beginning to understand.

Television. Studies show that children with ADHD watch more television and are twice as likely to have a television in their bedroom.11-13 It remains unclear whether ADHD leads to more hours of TV or if more hours of TV leads to ADHD. The effect of television viewing on childhood development may be a double-edged sword, with some evidence suggesting that high-quality educational programming can help children learn,14 and others suggesting that the quick pace of many television shows can diminish a young child’s ability to sustain attention.15

While some studies suggest that television viewing is associated with attention difficulties, other research suggests that confounding factors might account for these correlations.14,16

Video games. For children with ADHD, who have an increased drive to satisfy the reward pathways of the brain, video games may be particularly appealing but highly problematic. Video games can be engaging, fast-paced, motivating, and rewarding for many children. While no consensus exists about the definition of “problematic” video game use, a core feature is the neglect of other essential activities, such as learning, socializing, and self-care, in favor of playing.17

Children with ADHD are significantly more likely to play video games for greater than 1 hour per day than are their unaffected peers, which corresponds to higher scores of inattention and higher scores on measures of addiction or problematic use.13,18

Perhaps because of their motivation-seeking nature, many children with ADHD appear to focus intently on rapidly stimulating video games despite being inattentive in other settings. Parents may believe that children with ADHD immerse themselves in video games because they are good at them. Nevertheless, some research suggests that children with ADHD perform worse on video games than do unaffected children, and that their “strength” at playing video games might be relative to their weaknesses in academics or other areas.17

With the proliferation of online multiplayer games, video games now have the potential to become an avenue for social interaction. Given the social difficulties that may come with ADHD, affected children may accept this online culture as their virtual peer group, furthering their isolation from other peers in the real world.

The Internet. Researchers have devoted much attention to the link between ADHD and Internet use, recognizing that ADHD increases the risk of addictive behavior. Internet addiction has become a very real phenomenon. In several studies, ADHD has been found to be strongly correlated with Internet addiction among adolescents, college students, and adults.17,19,20 One study linked ADHD in elementary school children with Internet addiction.21 Furthering the link between ADHD and Internet addiction is the finding that treatment with methylphenidate may reduce the “severity” of Internet video game addiction.22

ADHD potentially exacerbates any negative consequences of digital media. The link between ADHD and digital media still needs clarification, particularly in younger children, but clinicians and parents alike must remain vigilant of children’s use of digital media, particularly if there is concern about the presence of ADHD.

With an understanding of the pervasive nature of ADHD across the lifespan, let’s reconsider the case of Jimmy discussed above. He is inattentive and fidgety, is experiencing academic and social difficulties, and seems to have an unhealthy pattern of video game playing, according to his mother. It is easy to think of Jimmy as falling in line with the worrisome trajectory that many children with ADHD face. But before coming to a diagnosis, we must heed his mother’s question: Is this truly ADHD, or could something else be causing or contributing to his difficulties?

Unraveling the Mystery

A thorough history is the best way to begin to investigate the nature of a child’s attention difficulties. In every case, we would like to know the answers to the following questions:

• What exactly are the problems?

• When did the problems start?

• Where do the problems occur?

• Under what circumstances do these problems arise?

• Why are the parents mentioning these problems now?

Start by asking about the child’s individual strengths and weaknesses, and then proceed using the biopsychosocial model to guide questioning. Ask questions about how a child relates to and functions within his or her family, peer groups, school, and community. Use validated tools to gather objective information about a child’s symptoms across settings. Through these approaches, clinicians can then begin to home in on a diagnosis of ADHD—or another diagnosis that may be the cause of inattention and school difficulties.

Emotional disorders. Primary anxiety or depression in school-aged children often goes underappreciated but can manifest with ADHD-like symptoms. Depressed children can appear agitated, distracted, or irritable; worried children also have significant difficulty focusing and can be quite fidgety. When thinking about mood problems, always consider the possibility of trauma.

Parents may ask about the possibility of their child having bipolar disorder, interpreting hyperactivity and irritability as signs of pathologic mood swings. This topic is fraught with controversy. The prevalence of true bipolar disorder ranges from 0.1% in 8- to 19-year-olds to 2.5% in adolescence, depending on how bipolar disorder is defined.

Furthermore, it is unclear whether irritability in children is a symptom of depression or a manic episode. Often it is difficult to tease out whether a child has emerging bipolar disorder or severe ADHD with emotional dysregulation, or if the two conditions coexist. Longitudinal studies seem to add to the confusion, since symptoms of hyperactivity and irritability often are considered criteria for both diagnoses, inflating the rates of comorbidity between the two diagnoses.

While research suggests that treatment with medication does not worsen mood symptoms in children with both ADHD and bipolar disorder, inadequate response to treatment may be a clue that the child’s clinical picture is much more complex and warrants further evaluation by a specialist.23

Learning disabilities. While children with learning disabilities may have some early struggles, their disabilities often are unidentified until third grade. This is when children shift from learning to read to reading to learn. Mathematics also becomes more complex, introducing multiplication, division, fractions, and even some algebra.

Children with learning disabilities can appear inattentive during tasks or activities that are difficult for them. Whereas a child with ADHD might answer math questions impulsively and make careless mistakes, a child with a mathematics learning disorder might become overwhelmed with a math task and become inattentive or disruptive.

A child with a reading disorder may have symptoms during reading activities and math word problems, further muddying the picture. These children also are prone to frustration, negative self-image, and mood problems.

Children with suspected learning problems need formal testing—usually psychological and academic testing, which may be provided through the public school system.

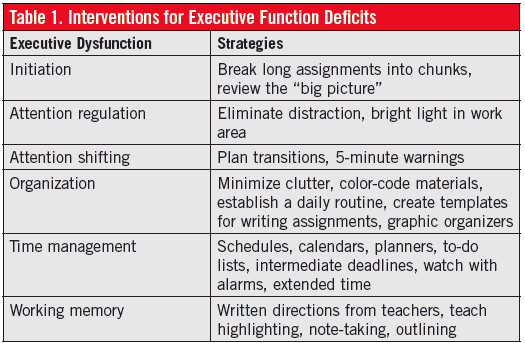

Executive dysfunction. Executive functions are higher-order cognitive abilities that include planning, cognitive flexibility, and self-regulation. These abilities are increasingly important to school success as children enter middle school, when students start changing classes and must balance the expectations of several different teachers. Behavioral inhibition, attention regulation, planning, organization, and working memory are among the many executive functions that students must rely on to meet these new demands. Deficits in any of these functions can lead to problems.

If grades are poor because of homework incompletion, find out in the history whether homework is completed but not turned in, whether it is never brought home in the first place, or whether it is a struggle to start. These are all problems with organization and initiation and suggest executive dysfunction. Addressing such problems effectively requires strategies specifically tailored to the observed type of dysfunction (Table 1). Although executive dysfunction often is part of ADHD, it can be a separate profile. Medication is unlikely to treat executive dysfunction effectively.

Social stressors. Sources of stress may come from within school (such as bullying, teacher-student mismatch, or classroom changes) or from outside of school (such as family crises). Children of any age may react to dramatic family events, such as marital conflict, illness, death, or financial difficulties, with symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, or hyperactivity. Asking probing questions can help gather more information:

• Did anything change at school? Did a teacher leave, a new kid join the class?

• What was going on in your family at the time? Was anyone ill? Were there any changes in your living situation?

• When school problems started, was that upsetting to the family? What happened?

When discussing bullying with a child, talking about other children helps demystify the problem and elicit information: “Some kids I know tell me about really mean kids in school who say mean things or make them feel bad. Have you seen anything like that?”

Hearing and vision. All children with inattention should undergo hearing screening and vision screening tests. In many cases, such children had been referred previously for a hearing or vision evaluation but never completed it.

Medications and foods. Diphenhydramine for allergies, β-agonists for asthma, and highly caffeinated beverages can impact a child’s level of activity and arousal during the day. Also ask about over-the-counter medications, some of which can make children tired and inattentive in school.

Many parents ask about dietary factors, dyes, and additives. One recent meta-analysis showed an effect of food color exclusion on reducing core symptoms of ADHD, but the effect size was much less than with medication. Supplementation of ω-3 fatty acids also had a small beneficial effect.24 Large studies on the topic of supplements and dietary restriction are lacking, and the current evidence is insufficient to recommend these approaches as evidence-based treatment.

Insufficient sleep. More independent at night, the school-aged child may be sleeping far less than is necessary without a parent knowing. If a child has difficulty waking for school and sleeps much later on weekends, he or she may be sleep-deprived, with inattention resulting. Ask about sleep environment, bedtime routines, and time of sleep onset and awakening. Also ask about snoring, gasping, pauses in breathing, or restlessness during sleep, since these may be signs of sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome.

Seizures. Rarely, a child with staring spells presents with concerns about inattention in school. Unlike the inattention of ADHD, seizures typically look like episodes of “zoning out” that cannot be interrupted by stimulation; absence seizures can occur midsentence, at any time of day, and are followed by complete lack of awareness of what happened.

Other medical conditions. When suggested by history or clinical course, consider thyroid abnormalities, lead poisoning, or fetal alcohol syndrome among the potential causes of ADHD symptoms.

The Complex Case

Often, a child’s inattention and hyperactivity cannot be explained by a single diagnosis. In fact, many of the conditions described here are frequent comorbidities of ADHD (Table 2).

Thinking again about Jimmy, he may have started with ADHD then developed comorbid depression or anxiety. He also may have an underlying learning disorder. We need to know about any changes in his family or social environment that have impacted his school performance. The following questions help clarify the confusing diagnostic picture:

• What came first? Was the child always “hyperactive” before developing learning problems?

• What is the biggest problem now? The more impairing problems should be treated first.

• What runs in the family?

When the diagnosis remains unclear, further evaluation by a specialist is necessary. Educational evaluations, including psychological and academic testing, often are helpful; for younger children, speech and language evaluations may unmask a language disorder that impairs learning.

When the diagnosis remains unclear, further evaluation by a specialist is necessary. Educational evaluations, including psychological and academic testing, often are helpful; for younger children, speech and language evaluations may unmask a language disorder that impairs learning.

Sometimes a child might have a number of minor weaknesses that do not rise to the level of a specific diagnosis but that combine to make learning and socialization difficult.

When the diagnosis includes ADHD, however, intervention is critical to reduce functional impairments. ADHD treatment should be guided by the history and should include medication as well as behavioral interventions such as parent training, school accommodations, or counseling, when indicated.

Attention to the developmental effects of ADHD at each stage of life, the new challenges that affected children face in the digital age, and possible comorbidities should help enhance the accuracy of ADHD diagnosis and success of management in the primary care office.

References:

1.

Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011; 128(5):1007-1022.

2.

Holmberg K, Hjern A. Bullying and attention-deficit–hyperactivity disorder in 10-year-olds in a Swedish community. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(2):134-138.

3.

Yang S-J, Stewart R, Kim J-M, et al. Differences in predictors of traditional and cyber-bullying: a 2-year longitudinal study in Korean school children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013; 22(5):309-318.

4.

Reinhardt MC, Reinhardt CAU. Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, comorbidities, and risk situations. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013;89(2):124-130.

5.

Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Jacobsen SJ. Long-term school outcomes for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based perspective. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(4):265-273.

6.

Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE Jr, Molina BS, et al. Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(1):27-41.

7.

Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Olazagasti MAR, et al. Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1295-1303.

8.

Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Katusic SK. Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2013; 131(4):637-644.

9.

Nigg JT. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and adverse health outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(2):215-228.

10.

Taurines R, Schmitt J, Renner T, Conner AC, Warnke A, Romanos M. Developmental comorbidity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2010;2(4):267-289.

11.

Acevedo-Polakovich ID, Lorch EP, Milich R, Ashby RD. Disentangling the relation between television viewing and cognitive processes in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comparison children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(4):354-360.

12.

Lingineni RK, Biswas S, Ahmad N, Jackson BE, Bae S, Singh KP. Factors associated with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among US children: results from a national survey. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:50. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-12-50.

13.

Mazurek MO, Engelhardt CR. Video game use in boys with autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, or typical development. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2): 260-266.

14.

Schmidt ME, Vandewater EA. Media and attention, cognition, and school achievement. Future Child. 2008;18(1):63-85.

15.

Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ, DiGiuseppe DL, McCarty CA. Early television exposure and subsequent attentional problems in children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):708-713.

16.

Ferguson CJ. The influence of television and video game use on attention and school problems: a multivariate analysis with other risk factors controlled. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(6):

808-813.

17.

Weiss MD, Baer S, Allan BA, Saran K, Schibuk H. The screens culture: impact on ADHD. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2011;3(4):327-334.

18.

Chan PA, Rabinowitz T. A cross-sectional analysis of video games and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in adolescents. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;5:16. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-5-16.

19.

Yen, J-Y, Ko C-H, Yen C-F, Wu H-Y, Yang M-J. The comorbid psychiatric symptoms of Internet addiction: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, social phobia, and hostility. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(1):93-98.

20.

Ko C-H, Yen J-Y, Yen C-F, Chen C-S, Chen C-C. The association between Internet addiction and psychiatric disorder: a review of the literature. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(1):1-8.

21.

Yoo HJ, Choo SC, Ha J, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and internet addiction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(5):487-494.

22.

Han DH, Lee YS, Na C, et al. The effect of methylphenidate on Internet video game play in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):251-256.

23.

Pataki C, Carlson GA. The comorbidity of ADHD and bipolar disorder: any less confusion? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(7):372.

24.

Sonuga-Barke EJ, Brandeis D, Cortese S, et al; European ADHD Guidelines Group. Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):275-289.

25.

Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. J Pediatr Psychology. 2007;32(6):631-642.

26.

DuPaul GJ, Gormley MJ, Laracy SD. Comorbidity of LD and ADHD: implications of DSM-5 for assessment and treatment. J Learn Disabil. 2013; 46(1):43-51.

Dr Schwartz is a fellow in developmental behavioral pediatrics at the Developmental Medicine Center at Boston Children’s Hospital. Dr Schonwald is the medical director of Developmental Behavioral Outreach at Boston Children’s Hospital an assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School in Boston.