Allergic Eye Disorders: Identification—and Alleviation

ABSTRACT: Signs and symptoms of a full-blown ocular allergic reaction include deep red vessels in the conjunctiva, itching, and swelling of the conjunctiva and eyelids. Ocular allergy can resemble nonallergic conditions, including drug-induced conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and viral or bacterial infection. A history of itching strongly suggests a diagnosis of allergy. To distinguish allergic conjunctivitis from more serious allergic ocular diseases, inspect the lids and cornea for papillae on the upper tarsal surface, which occur in giant papillary conjunctivitis and vernal or atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Local treatment of allergic conjunctivitis consists of over-the-counter and prescription antihistamines, with or without vasoconstrictors or mast cell stabilizers. Combination mast cell stabilizer/antihistamine topical ophthalmic agents are considered the most effective treatment of allergic conjunctivitis. Oral antihistamines are not indicated unless a patient has an allergic condition, such as rhinitis, dermatitis, or asthma. The newer intranasal corticosteroids may also be effective in some pediatric patients with allergic rhinitis.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In recent years, the incidence of allergy has been rising. Ocular allergy is a component of many patients’ allergic picture that has historically been overlooked, despite the fact that it affects health and quality of life. Recent estimates suggest 15% to 40% of the population suffer from either seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC) or perennial allergic conjunctivitis (PAC).1

The diagnosis and treatment of ocular allergy have fallen increasingly into the domain of the primary care/pediatric clinician. Yet even the general ophthalmologist may sometimes find it difficult to differentiate ocular allergy from other disorders of the eye.

Ocular allergy is a common condition that is frequently self-diagnosed and self-treated by patients or parents, which in turn, increases the chances for misdiagnosis and mistreatment. A few pertinent questions on a medical history questionnaire can quickly elicit a history of ocular allergy even when patients have no active symptoms at the time of the visit.

In this article, we summarize the basic science of ocular allergy and offer a practical guide to diagnosis and treatment. We also review the chief mimics of ocular allergy to help eliminate the confusion that can lead to misdiagnosis.

THE ALLERGIC RESPONSE

Ocular allergy occurs when airborne allergens come into contact with the tear film, attaching to receptors on immunologically active mast cells that reside in the more superficial layers of the conjunctival surface. These receptors are actually small sections of the IgE antibody, embedded on one side in the mast cell membrane and, on the other, open to the extracellular spaces, waiting like a trap for the allergen to wash over them from the tear film.2

The binding of antigen to IgE antibody on the mast cell surface triggers a cascade of chemical reactions that leads to the degranulation of the mast cell and release of the allergic chemokines or mediators of the “allergic reaction.” These mast cell granules contain histamine—among other inflammatory modulators—which is one of the most important chemokines with regard to allergy and the acute allergic response.

Histamine. This mediator is the only one released from the mast cell that can account for all of the signs and symptoms of ocular allergy. By binding to H1 receptors on local conjunctival vessel walls, it causes a generalized vasoactive response, dilating vessels and increasing vessel permeability. Both of these processes lead to the ocular redness, tearing, and conjunctival and lid swelling seen directly after exposure to allergens. The response is rapid because the histamine is preformed and released within minutes of allergen exposure.

Pruritus is caused by H1-receptor activation on local nerve endings rather than on vessels.3 Intense itching follows allergic exposure; it peaks within minutes, after which it generally wanes, as long as the allergen exposure is not continuous.4

The itching associated with histamine release, although intense, is typically not prolonged in an episode of SAC because of the almost immediate breakdown of this mediator into its inactive form by histaminase enzymes.5 Thus the duration of the histamine-directed reaction is internally regulated and self-limited. However, the duration and severity of this reaction can be extended by manual stimulation of mast cells; rubbing of the eyes can cause further mast cell degranulation and release of histamine.6

Despite the brevity of most histamine-induced signs and symptoms, their effect can be more long-lasting; skin and collagen fiber damage can become evident around the eyes as a result of repeated stretching and swelling of the eyelids. In chronic vision-threatening diseases, such as vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) and atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC), cells and mediators work to sustain a late-phase reaction that results in tissue damage.

Other mediators. These have a smaller role in the acute allergic reaction. They include tryptase, platelet-activating factor, prostaglandin D2, and leukotrienes. Prostaglandin D2 appears to be the most active in immediate allergic reactions of the eye; it contributes to the processes that cause redness, chemosis, mucus discharge, and eosinophilic infiltrate. Administration of this mediator reproduces only the clinical signs (ie, redness and chemosis) of allergic conjunctivitis in humans and animals.7 In contrast to SAC—during which short-term, immediate effects of allergy come and go quickly—more severe forms of ocular allergy include late-phase reactions that recruit inflammatory cell infiltrates that set up the tissue for more chronic and profound inflammatory changes, rather than just allergic changes.8

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF ALLERGIC CONJUNCTIVITIS

The signs of a full-blown acute allergic reaction include deep red vessels in the conjunctiva and sometimes chemosis, a ballooning of this tissue over the sclera. What appears to be air under the thin plastic wrap–like tissue is actually fluid that has leaked from the vessels. Tearing may or may not be evident. If the reaction has just occurred, itching is intense. This tapers off relatively quickly, although rubbing of the eyes causes further mast cell degranulation, which can prolong the reaction. Swelling can affect the upper and lower lids; it peaks approximately 15 minutes after the reaction has begun and lasts longer than other signs. The Figure shows chemosis from release of histamine following an allergen challenge.

You will rarely see a patient in this condition, however, because the acute reaction occurs immediately after contact with the offending allergen. Patients are likelier to present with a more subdued reaction: conjunctival redness, slight edema, and itching that comes and goes.

Ask the patient when the itching occurs. If he or she mentions during outdoor activities, a pollen-related allergic sensitivity can be presumed. If the reaction typically occurs indoors, questions about the presence of pets, carpeting, and other indoor factors may reveal an animal dander or mite sensitivity. Keep in mind that patients may visit your office in the off season; it still is important to ascertain whether allergies occur at other times of the year in order to prepare patients with appropriate treatments.

A history of other types of allergy—such as rhinitis, asthma, or eczema—immediately defines the nature of the ocular reaction. Only rarely does an allergic person have allergies that manifest in only one tissue, although an ocular sensitivity may be new to the patient.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

SAC or PAC can mimic other allergic conditions—such as VKC, giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC), and AKC. It may also mimic nonallergic conditions, such as drug-induced conjunctivitis, dry eye, blepharitis, viral or bacterial infection, and chlamydial infection. (Although GPC is not truly an allergy, it is often categorized among other allergy types, which all produce redness.) Table 1 summarizes the principal signs and symptoms of these disorders.

The key symptom in the diagnosis of allergy is itching. Patients without itching, or a recent history of itching, do not have an allergy. Ask patients to be specific in describing their symptoms, because pain, foreign-body sensation, burning, and general discomfort are not diagnostic for any ocular disease.

If the patient assures you that he has itching, inspect the upper lids and cornea for signs of more serious allergic disease. This is an important step in distinguishing allergic conjunctivitis from VKC, AKC, and GPC. These entities are all characterized by papillae on the upper tarsal surface and are best treated by an ophthalmologist.

VKC. This serious disorder is characterized by irregularly sized hypertrophic papillae, which results in the classic “cobblestone” appearance on the upper tarsal plate. Giant papillae are 1 mm or larger and may be distributed over the entire tarsal area or limited to one isolated zone. More rarely, giant papillae may also form on the lower tarsal conjunctiva.

VKC is characteristically associated with intense, constant itching. It is seen predominantly in prepubescent children and affects boys 3 times more often than girls.9 Suspect VKC if infiltrates, punctate keratitis, opacities, ulcers, or photophobia—the hallmark signs of corneal involvement—are present.

AKC may feature papillae similar to those in VKC. This severe inflammatory disease usually occurs in males. It almost always has a dermal component, with eczema visible around the eyes and on other parts of the body. The cornea is often involved, and chronic ulcers are sometimes seen.

GPC. This condition can usually be excluded if the patient is not a contact lens wearer and has no protuberances—such as stitches or anatomic lid/corneal anomalies—that simulate a foreign body and elicit an irritative and inflammatory response. GPC may be exacerbated by allergy but is primarily the result of mechanical irritation. Papillae associated with GPC are usually larger than 0.3 mm; they can cover the entire tarsal surface or be limited to just one growth, with a vascular supply radiating from the center of each. A second definitive sign of GPC is a stringy, sheet-like mucus discharge.

Drug-induced conjunctivitis, or conjunctivitis medicamentosa, can occur in the pediatric population. Frequent use of topical vasoconstrictive drops is an example. The principal signs are severe redness and swelling; the eyelids and inferior conjunctiva are typically involved.

Dry eye is the result of activities in which the blink rate is decreased. These include reading, watching television, driving, and computer work/games. The eyes are red and irritated, and the patient often complains of a gritty or foreign-body sensation in the eyes. Pulling out and down on the lower lid may demonstrate the absence of a tear meniscus in many patients with dry eye.

Dry eye and allergy share several symptoms, and one condition may underlie the other. The presence of dry eye makes the ocular surface more “sticky,” which allows airborne allergens to adhere longer and accumulate on the eye. Alternatively, a patient with allergic rhinitis may be taking oral antihistamines; some of these agents (more frequent with earlier antihistamines) can significantly reduce tear flow and volume, which results in relatively dry eyes.

The key to the diagnosis is to ask the appropriate questions. Be sure patients and/or parents can differentiate between itching and burning; ask whether they are taking medications that may be drying and whether environmental factors exacerbate their symptoms. Irritation during dry, warm, windy conditions or during visual tasks, such as watching television, indicates dry eye; itching of the eyes while outdoors or near pets or dust suggests allergy.

Dry eye can also be a problem in patients with blepharitis. In patients with this inflammatory disorder, the meibomian glands, which secrete oils that lie on top of the tear film and protect it from drying out, are blocked. The oil layer of the tear film is insufficient, which leads to greater evaporation of the tear film and red, irritated, dry eyes. Red, puffy, oily lids are also common. Blepharitis is commonly misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed, even by ophthalmologists, and is frequently confused with allergic or infectious conjunctivitis. It is often easily treated by daily application of hot compresses and gentle washing with baby shampoo.

Infection can be inferred from the presence of purulent discharge and eyelids that are stuck together in the morning. Viral infection does not always manifest with purulent discharge; patients may have a thin mucus discharge similar to that seen in allergy. Itching may also be present. However, the high level of discomfort and the occasional corneal involvement—such as keratitis or infiltrates—generally suggests viral infection, which accounts for 95% of cases of infectious conjunctivitis.

Chlamydial conjunctivitis is usually chronic; it is characterized by the presence of follicles—small, raised pink growths filled with cellular infiltrate. Although follicles are sometimes seen in perennial allergy, they are associated only with chronic processes (unlike the seasonal cycles that define true allergic conjunctivitis). A distinctive feature of chlamydial infection is the prevalence of lower lid and fornix inflammation, rather than the upper tarsal conjunctival involvement seen in most forms of allergy.

TREATMENT

Avoidance of allergen is the first line of defense in treating allergy; however, avoidance measures are often impractical or impossible. Most patients cannot stay indoors in air-conditioning all the time to avoid seasonal pollen reactions. Mite allergy can sometimes be controlled with the use of new pillows with mite-control zippered cases and mattress covers, synthetic comforters and blankets, and laundering of bedding in very hot water. Carpets and stuffed animals should be removed from the bedroom.

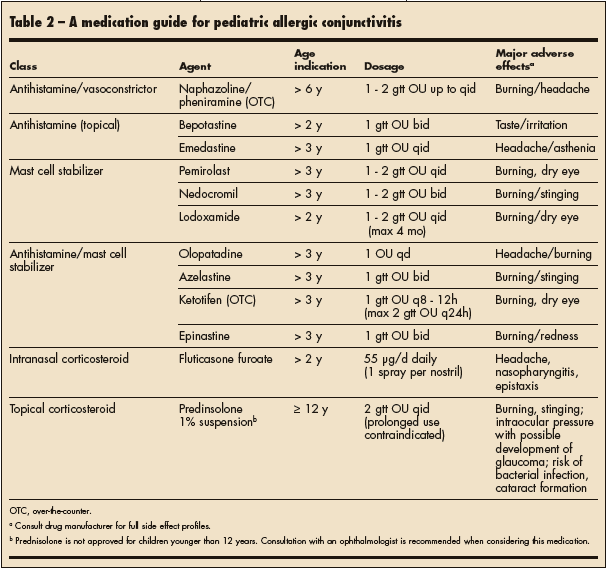

Antihistamines. Local treatment consists of over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription preparations of eye medications (Table 2). Most contain an H1-receptor antihistamine, with or without a mast cell stabilizer or an a-adrenergic agonist acting as a vasoconstrictor. The first-generation antihistamines (eg, pheniramine) are very short-acting and usually do little to alleviate redness, which is why they are usually formulated with a vasoconstrictor (naphazoline). Nevertheless, these formulations have been used for many years, have a proven safety record, and are now available without a prescription. Their duration of action of about 2 hours and maximum dosing frequency of 4 times per day means that these agents must be applied frequently, and even then they may not provide day-long coverage. Thus it may be more convenient for a patient to buy one bottle of a more potent prescription agent than several bottles of a short-acting OTC antihistamine. However, even newer antihistamine agents (eg, bepotastine, emedastine), although more potent and long-acting, inhibit redness and itching for just 3 to 4 hours.

Mast cell stabilizers. The first mast cell stabilizer to appear on the market was cromolyn sodium. Newer agents, including nedocromil, lodoxamide, and pemirolast, are more effective.10-12 These drops generally require a loading period of several weeks and need to be used regularly regardless of whether symptoms are present, since they must keep the mast cells constantly stabilized in the face of allergen exposure. In contrast, antihistamines relieve the effects of histamine after it is released and therefore can be taken even during a full-blown allergic reaction.

Multi-action drugs. Olopatadine, azelastine, and ketotifen combine antihistaminic and mast cell–stabilizing activity. Olopatadine is indicated for the treatment of all signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis and even when used for allergic rhinitis shows some benefit in patients who have both conditions.13 Azelastine is indicated only for treatment of itching, and ketotifen is indicated for temporary prevention of itching.

New agents. A new formulation of the olopatadine molecule in a more potent concentration (0.2%) has been shown to last 16 to 24 hours, which allows for a once-daily regimen. It has been shown to be a very potent mast cell stabilizer. Epinastine is a newer antihistamine with mast cell–stabilizing activity that lasts for 8 to 12 hours.14,15

Oral antihistamines do not relieve the symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis effectively and may even exacerbate them due to their impact on tear production. Comparative studies have shown that local treatment is superior to systemic treatment.16 Furthermore, even newer antihistamines, such as loratadine, have been shown to cause ocular drying, which results in less dilution of allergens from the ocular surface and less dilution of mediators once an allergic reaction ensues.17 Drying also increases the patient’s discomfort and decreases his tolerance to conditions that predispose to drying, such as working on a computer.

A good rule of thumb is: if a patient has no other allergic conditions—such as rhinitis, dermatitis, or asthma—oral antihistamines are not indicated. Topical disease should be treated topically. Evidence shows that for patients with ocular and nasal symptoms, a dual-action mast cell stabilizer/antihistamine eye drop (for the ocular component) and a corticosteroid nasal spray (for rhinitis) are more effective in combination than an oral antihistamine and nasal spray.18 Because of drainage of eye drops through the nasolacrimal ducts, the ocularly instilled agent can also help relieve nasal symptoms.

As is the case with all seasonal allergic problems, consider giving your patients a prescription for a potent anti-allergy eye drop before the next allergy season. Starting treatment early greatly enhances effective control of symptoms.

Intranasal corticosteroids are not the first-line agent used for patients with either SAC or PAC. Use of fluticasone furoate, a newer product approved for children 2 years and older, has been shown to decrease symptoms of SAC and PAC in patients with allergic rhinitis and concurrent allergic conjunctivitis.19 The older intranasal corticosteroids do not demonstrate this effect.