Celiac Disease in the Pediatric Population: Could You Be Missing the Diagnosis?

ABSTRACT: Celiac disease is a life-long autoimmune disorder of the small intestine caused by exposure to gluten. Classic symptoms of celiac disease include gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and diarrhea. In the pediatric population, a large number of patients present with extraintestinal symptoms such as joint pain, anemia, and neurologic symptoms, often resulting in a delay in the diagnosis of celiac disease. Pediatricians can screen for celiac disease with various serologic tests such as tissue transglutaminase antibodies; however, the gold standard for diagnosis is histologic evaluation of duodenal tissue obtained during upper endoscopy. Typical endoscopic findings are mucosal atrophy, fissuring, and scalloping. Currently, the only treatment for celiac disease is strict and life-long adherence to a gluten-free diet. The management of pediatric celiac disease also involves monitoring and repletion of vitamins and minerals, screening for other autoimmune diseases including thyroid disease and diabetes mellitus, and close observation of growth and height velocity in the developing child.

Key words: celiac disease, gluten-free diet, antibody, endoscopy, histology

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder of the small intestine after exposure to the gliadin component of gluten in the diet. Celiac disease is common and is estimated to occur in 0.5% to 1% of the general population, although the exact prevalence has yet to be determined in the pediatric population. Symptoms of celiac disease include both gastrointestinal symptoms, such as bloating, weight loss, abdominal distention and abdominal pain, as well as extraintestinal symptoms, such as various skin, rheumatologic, dental, and neurologic complaints. Serologic testing is useful for screening for the diagnosis, although the diagnosis cannot be confirmed without histologic evaluation of duodenal and/or jejunal biopsies. After the biopsies are confirmed to be consistent with celiac disease, a life-long gluten-free diet is essential for resolution.

In this review, we offer practical suggestions that address the principal components of diagnosis and management of celiac disease in the pediatric population.

HISTORY

The cause of celiac disease was not known with certainty until the 1940s when the Dutch pediatrician William Dicke noticed the dramatic improvement in celiac disease symptoms among Dutch children coinciding with the time of the bread shortage during World War II. He subsequently found that these symptoms returned once bread was re-introduced into the children’s diets after the war ended. Researchers then discovered that wheat, barley, rye and to a lesser degree oats triggered a malabsorption syndrome that resolved with the elimination of these products. Further work isolated the toxic agent in gluten, the alcohol-soluble fraction of wheat protein.

Celiac disease is neither a food allergy nor a result of food intolerance—a concept that may confuse many patients. Although chronic skin diseases such as dermatitis herpetiformis are linked with celiac disease, there is rarely an associated or immediate urticarial reaction in response to gluten ingestion as is seen in true allergic reactions. Unlike a food intolerance (such as lactose or fructose intolerance) which usually produces GI symptoms within hours of exposure, the mucosal changes of celiac disease occur over months to years and are not temporally related to day-to-day dietary exposure.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of celiac disease has likely been underestimated for quite some time. Currently, the prevalence worldwide is estimated to be 0.5% to 1%, and in the United States it has been estimated to be as high as 1 in 133 previously healthy individuals.1,2 The exact prevalence has not yet been determined in the pediatric population. Twice as many females are diagnosed as males, and the disease affects individuals of all ages. Certain individuals are considered to be at higher risk for developing celiac disease including those who have first-degree relatives with a confirmed diagnosis as well as individuals with a history of anemia, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, and certain genetic disorders including Down syndrome and Turner syndrome. Celiac disease is less common in nonwhite individuals and is most frequently seen in Europe and in countries to which Europeans have emigrated (such as the United States and Australia). First-degree relatives of affected persons have a roughly 10-fold risk of celiac disease, and there is a more than 70% concordance in identical twins. This evidence supports the notion that although there is a dietary trigger, celiac disease also has a strong genetic component.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The diagnosis of celiac disease is often delayed as classic gastrointestinal symptoms are not always present (particularly in the pediatric population). Only a small minority of patients present with the textbook symptoms of malabsorptive diarrhea with steatorrhea, weight loss, and nutritional deficiencies (usually folate and iron). Many persons have a subclinical enteropathy. Others have GI complaints without constitutional symptoms, which may suggest a symptom profile of irritable bowel syndrome.3 Others still may have persistent travelers’ diarrhea.4 Many of the symptoms of celiac disease are extraintestinal, such as anemia, joint pain, neurologic symptoms, or skin manifestations, and can result in visits to several specialists including neurologists, hematologists, dermatologists, and rheumatologists before a gastroenterologist becomes involved. The average length of time it takes for an individual to be diagnosed with celiac disease in the United States is 4 years,5 and it is believed that the disease is still

underdiagnosed.

The numerous extraintestinal manifestations and conditions associated with celiac disease are listed in Table 1.6-8 Some extraintestinal manifestations, such as dermatitis herpetiformis, have a causative relationship with celiac disease; 85% of patients with this skin condition have celiac disease on duodenal biopsy, almost all are serologically positive for celiac disease, and most respond to a gluten-free diet. Other disorders, such as autoimmune thyroid disease and type 1 diabetes, may be genetically linked, but usually do not improve with a gluten-free diet.9,10

Celiac disease is associated with a host of neurologic sequelae including neuropathy, ataxia, and epilepsy, the neuropathophysiology of which we are just beginning to understand.11 In one study, the incidence of malignancy, the most feared complication of celiac disease, was 1.3 compared with the incidence in the general population with a commensurate rise in mortality from malignancy.12 With extended follow-up, however, the 1.3 figure did trend toward unity. Cancer was diagnosed in 249 of 12,000 persons with celiac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis who were followed from 1964 to 1994. The incidence of malignant lymphoma showed the most dramatic increase and accounted for 18% of cancers. The incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, duodenal and colonic adenomas, and hepatocellular carcinoma also increased modestly.

Celiac disease is associated with a host of neurologic sequelae including neuropathy, ataxia, and epilepsy, the neuropathophysiology of which we are just beginning to understand.11 In one study, the incidence of malignancy, the most feared complication of celiac disease, was 1.3 compared with the incidence in the general population with a commensurate rise in mortality from malignancy.12 With extended follow-up, however, the 1.3 figure did trend toward unity. Cancer was diagnosed in 249 of 12,000 persons with celiac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis who were followed from 1964 to 1994. The incidence of malignant lymphoma showed the most dramatic increase and accounted for 18% of cancers. The incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, duodenal and colonic adenomas, and hepatocellular carcinoma also increased modestly.

DIAGNOSIS

History and physical examination. If celiac disease is suspected, a thorough history and physical examination are in order. Patients should be carefully asked about GI symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, and/or irritable bowel symptoms. An extensive review of systems is warranted and should focus on constitutional signs (weight loss and fatigue) and extraintestinal manifestations (skin lesions, joint pain, neurologic symptoms, and oral aphthae). Highlights of the physical examination include inspection for de-enamelization of the teeth, muscle atrophy, and kyphosis. Although most patients with active celiac disease tend to be thin, overweight patients may have latent or active celiac disease and this diagnosis should be considered in the appropriate clinical setting.

Routine laboratory testing. Screening laboratory tests should include a complete blood cell count; mean cell volume; red blood cell distribution width; and iron, vitamin B12, and folate levels. Because celiac disease is largely a disease of the proximal small bowel, patients typically have low folate and iron levels but normal B12 levels as B12 is absorbed further down in the terminal ileum. This is in contrast to tropical sprue, a disease with a similar phenotype, which involves the entire small bowel, including the ileum, and often produces both B12 and folate deficiency. Erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR) may be normal or mildly elevated. Hypoalbuminemia may suggest a protein-losing enteropathy. In patients with chronic diarrhea, stool should be examined for fecal fat looking for malabsorption (abnormal results should be confirmed with a 72-hour stool collection for fecal fat) as well as infectious causes including ova, parasites, Giardia antigen, and Clostridium difficile.

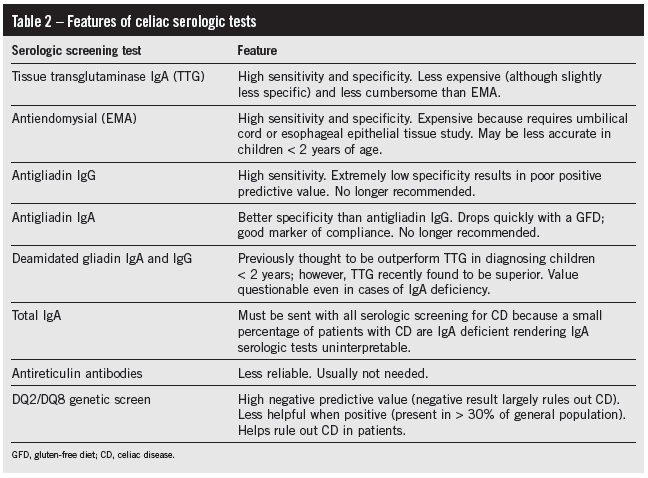

Serologic testing. The availability of accurate serologic tests has greatly facilitated the diagnosis of celiac disease. The principal features of these tests are reviewed in Table 2.

Although upper endoscopy with histologic analysis of intestinal biopsies is still considered the gold standard of diagnosis, positive serologic testing can help the pediatrician identify those individuals in whom an upper endoscopy should be performed. Commercially available serologic tests include anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA (TTG), anti-gliadin IgA and IgG (AGA IgA and IgG), deamidated gliadin IgA and IgG, anti-endomysium IgA (EMA), and anti-reticulin IgA (ARA). The sensitivity and specificity of these tests vary, often rendering them difficult to interpret. In children, the sensitivity and specificity of both AGA IgA and AGA IgG are poor, which has led some experts (including the authors of the NIH consensus statement) to discourage their use. Previous evidence suggested that the deamidated anti-gliadin IgA and IgG were more promising in terms of improved sensitivity and specificity particularly in children younger than 2 years of age. However, data from a recent study published in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition suggest that TTG remains superior to deamidated anti-gliadin even in children under the age of 2 years. The authors also suggest that using deamidated anti-gliadin as a complement to TTG during diagnosis rendered few additional diagnoses of celiac disease and added considerable cost to the workup as well as unnecessary endoscopies, thus exposing children to anesthesia unnecessarily.13

Although upper endoscopy with histologic analysis of intestinal biopsies is still considered the gold standard of diagnosis, positive serologic testing can help the pediatrician identify those individuals in whom an upper endoscopy should be performed. Commercially available serologic tests include anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA (TTG), anti-gliadin IgA and IgG (AGA IgA and IgG), deamidated gliadin IgA and IgG, anti-endomysium IgA (EMA), and anti-reticulin IgA (ARA). The sensitivity and specificity of these tests vary, often rendering them difficult to interpret. In children, the sensitivity and specificity of both AGA IgA and AGA IgG are poor, which has led some experts (including the authors of the NIH consensus statement) to discourage their use. Previous evidence suggested that the deamidated anti-gliadin IgA and IgG were more promising in terms of improved sensitivity and specificity particularly in children younger than 2 years of age. However, data from a recent study published in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition suggest that TTG remains superior to deamidated anti-gliadin even in children under the age of 2 years. The authors also suggest that using deamidated anti-gliadin as a complement to TTG during diagnosis rendered few additional diagnoses of celiac disease and added considerable cost to the workup as well as unnecessary endoscopies, thus exposing children to anesthesia unnecessarily.13

The sensitivity of EMA in children ranges from 0.88 to 1 with a specificity between 0.91 and 1. Notably the EMA may be less sensitive in children under 2 years of age. The sensitivity of TTG in children ranges from 0.92 to 1 with the specificity ranging between 0.91 and 1. Given these data, EMA and TTG are considered to be highly sensitive and specific tests for screening children for celiac disease. Based on evidence and the consideration of cost, it is recommended that pediatricians send TTG when screening children for celiac disease. A total IgA (to rule out IgA deficiency which may result in falsely negative serologic testing) must be sent along with the TTG as IgA deficiency is common in patients with celiac disease.1

It is important to remember that in a patient with a high clinical likelihood of celiac disease, negative results on serologic testing do not rule out the diagnosis of celiac disease and that duodenal biopsies must still be obtained in order to make a definitive diagnosis.

Figure 1 – An endoscopic view of the proximal small bowel demonstrates a scalloped appearance of the mucosa. This is a classic characteristic of celiac disease.

(Photo courtesy of John Godino, MD.)

Duodenal biopsy. Biopsies should be obtained from both the bulb and distal duodenum. Typical endoscopic findings in celiac disease include mucosal atrophy, fissuring, and scalloping (where fissures cross over folds) (Figure 1). Histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens typically reveals villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia (Figure 2), but in the early stages may only demonstrate nonspecific lymphocytic infiltration with normal villous architecture.

After positive serology is found in pediatric patients, many parents often ask if they can simply start their children on a gluten-free diet without performing an endoscopy. However there are several reasons why this is not advised including the following: false-positive serology can occur which would lead to unnecessary implementation of a life-altering gluten-free diet, symptomatic improvement with a gluten-free diet is not specific and is susceptible to placebo effect, and upper endoscopy is a safe and simple procedure. Additionally, it is much more difficult to rule out the diagnosis if one is on a gluten-free diet because of potential normalization of serologic studies and biopsies.

A caveat in the endoscopic diagnosis is that the grossly normal appearance of duodenal mucosa does not obviate the need for biopsy. Gross mucosal signs such as mosaicism or scalloping are only 50% sensitive compared with the gold standard of histologic assessment.14 However, histologic evaluation is also subject to error in cases of inadequate sampling (at least six biopsies from the duodenum and two biopsies from the duodenal bulb should be taken), failure to report a gluten-free diet, and inadequate experience of the pathologist evaluating the biopsies.

Genetic testing. Diagnosis is more difficult in a patient who has self-initiated a gluten-free diet because results of serologic tests and duodenal histologic assessments may be falsely negative. In these patients, a gluten rechallenge should be instituted for at least 4 weeks followed by repeat serologic testing and upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies. Because many patients are reluctant to undergo these steps, a genetic screen for HLA DQ2 and HLA DQ8 may be sent. The presence of HLA DQ2 and HLA DQ8 is strongly associated with celiac disease. It has been estimated that 90% to 95% of patients with celiac disease are positive for DQ2 and those negative for DQ2 are typically positive for DQ8.15 The absence of DQ2 and DQ8 essentially excludes the diagnosis of celiac disease. This test is considered necessary but not sufficient for the diagnosis. Therefore, unless the likelihood of disease is extraordinarily high, a negative result largely rules out the diagnosis. A positive result, however, sheds no light, because the alleles are carried in approximately 30% of the general population.

MANAGEMENT

MANAGEMENT

Treatment of celiac disease consists of a life-long and strict adherence to a gluten-free diet. Products that contain wheat, barley, and rye must be avoided. Oats are generally forbidden as well because of cross-contamination by other grains in production in many facilities. A gluten-free diet is extremely effective although admittedly difficult because of the centrality of grains to the Western diet and the widespread presence of gluten in processed foods. However, patients usually experience such dramatic improvement in their symptoms (both gastrointestinal and extraintestinal) and in their general sense of well-being that they typically adjust to the diet quickly and without resistance. Consultation with a clinical dietitian is particularly useful in the management of celiac disease especially just after confirming the diagnosis so that the patient and family can receive standardized information about the gluten-free diet. Dieticians can also be immensely helpful in directing patients and families to appropriate products, restaurants, and support groups.

If a patient does not respond to a gluten-free diet within 6 months or has a persistently elevated TTG level, the most likely cause is continued gluten exposure of which the patient may or may not be aware. The occasional patient with refractory celiac disease requires corticosteroids, but the focus generally should be on scrutinizing the diet. In general, we recommend that all of our patients with celiac disease undergo nutritional evaluation at least once a year with our clinical dietician for a refresher on the gluten-free diet and appropriate preparation of food in a home with other family members who do eat gluten particularly in the case of persistent symptoms or persistently elevated TTG level. Some studies have suggested beneficial effects of probiotics on mucosal immunity as well as the capacity to hydrolyze gliadin polypeptides; however, their role remains unclear.16

Other management considerations include repletion of iron, folate and calcium, and vitamin D as needed. Vitamin B12 is usually unaffected given its absorption distally in the terminal ileum. With regard to vaccination status, the vaccine schedule recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and the American Academy of Pediatrics should be followed in patients with celiac disease. Pneumococcal vaccination is especially recommended because of the high prevalence of hyposplenism among patients with celiac disease.

Children with celiac disease should undergo screening for associated disorders such as thyroid disease and diabetes mellitus. Bone densitometry should be considered to evaluate for osteopenia given the common presence of nutritional deficiencies and age-appropriate cancer screening should be performed as well. Routine small-bowel imaging by small-bowel series is not recommended given the risks associated with ionizing radiation, and routine monitoring of the small bowel using capsule endoscopy is uncommon and typically not recommended.

SCREENING

Most experts do not recommend screening asymptomatic children for celiac disease except for cases where first-degree relatives have confirmed celiac disease. However, this must be sharply distinguished from screening in patients with GI symptoms or possibly related extraintestinal signs or symptoms, especially anemia, fatigue, premature osteoporosis, and the associated conditions listed in Table 1. In these settings, pursuing the diagnosis is strongly encouraged to reduce morbidity.n

REFERENCES:

1. Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multi-center study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:286-292.

2. Gujral N, Freeman HJ, Thomson AB. Celiac disease: prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(42):6036-6057.

3. Sanders DS, Carter MJ, Hurlstone DP, et al. Association of adult coeliac disease with irritable bowel syndrome: a case-control study in patients fulfilling ROME II criteria referred to secondary care. Lancet. 2001;358:1504-1508.

4. Landzberg BR, Connor BA. Persistent diarrhea in the returning traveler: think beyond persistent

infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:112-114.

5.Green PHR, Stavropoulos SN, Panagi SG, et al. Characteristics of adult celiac disease in the USA: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(1):126-131.

6. Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Celiac sprue. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:180-188.

7. Lubrano E, Ciacci C, Ames PR, et al. The arthritis of celiac disease. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:

1314-1318.

8. West J, Logan RF, Card TR, et al. Fracture risk in people with celiac disease: a population-based

cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:429-436.

9. Seissler J, Schott M, Boms S, et al. Autoantibodies to human tissue transglutaminase identify silent coeliac disease in Type I diabetes. Diabetologia. 1999;42:1440-1441.

10. Kordonouri O, Dieterich W, Schuppan D, et al. Autoantibodies to tissue transglutaminase are sensitive serological parameters for detecting silent coeliac disease in patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2000;6:441-444.

11. Bosworth BP, Landzberg BR. Neurologic manifestations of gastrointestinal and hepatic diseases. In: Gilman S, ed. Neurobiology of Disease. St Louis: Elsevier; 2006:689-701.

12. Askling J, Linet M, Gridley G, et al. Cancer incidence in a population-based cohort of individuals hospitalized with celiac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:

1428-1435.

13. Olen O, Gudjónsdóttir AH, Browaldh L, et al. Antibodies against deamidated gliadin peptides and tissue transglutaminase for diagnosis of pediatric celiac disease. J Pediatric Gastroenterol Nutrition. 2012;55:695-700.

14. Oxentenko AS, Grisolano SW, Murray JA, et al. The insensitivity of endoscopic markers in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:933-938.

15. Sollid LM, Markussen G, Ek J, et al. Evidence or a primary association of celiac disease to a particular HLA-DQ alpha/beta heterodimer. J Exp Med. 1989;169:345-350.

16. De Angelis M, Rizzello CG, Fasano A, et al. VSL#3 probiotic preparation has the capacity to hydrolyze gliadin polypeptides responsible for celiac sprue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:

80-93.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

•Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatric Gastroenterol Nutrition. 2005;40:1-19.