Constipation in the Hospitalized Older Patient: Part 2

Key words: Constipation, laxatives, enemas, gastrointestinal disorders, bowel movement.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

In acute care settings, constipation is known to affect a patient’s quality of life, social functioning, and cognitive and physical performance, all of which are predictors of healthcare use and healthcare costs.1-4 Constipation is common in older adults, accounting for 2.5 million physician visits and 92,000 hospitalizations in the United States annually,1,5,6 yet there is a lack of attention on ways to prevent constipation, to appropriately diagnose it, and to effectively manage and treat it in this complex population of older adults. Guidelines need to be developed to ensure that all elders have a proper bowel regimen while hospitalized. In the meantime, careful monitoring and screening of patients at risk of constipation is essential.

This article is the second part of a two-part article on constipation in the hospitalized older patient. Part 1, which was published in the previous issue of Clinical Geriatrics, provided a brief overview of constipation and discussed its complex pathophysiology and etiology in hospitalized elders. Part 2 reviews the clinical features of constipation, the nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modes of prevention, and the management strategies in these individuals.

Clinical Screening for Constipation

Symptoms of constipation may include an altered bowel movement regimen, prolonged straining, hard pellet-like stools, a feeling of incomplete emptying, abdominal pain and cramping, flatulence and bloating, hematochezia (ie, blood in the stool), nausea, vomiting, urinary dysfunction, poor appetite, weight loss, general malaise, and delirium. If left untreated, constipation may lead to fecal impaction, overflow fecal incontinence with loose bowel movements (eg, diarrhea), urinary incontinence, mechanical intestinal obstruction, and malnutrition. In light of these debilitating symptoms, persons with constipation may lose interest in physical activities, which may contribute to loss of muscle tone over time (eg, deconditioning). Constipation in hospitalized patients can also lead to cognitive dysfunction and delirium, which can cause a host of other complications, including falls and fall-related injuries, prolonged hospitalization, and increased morbidity and mortality.

Due to the myriad potential causes and contributing factors of constipation, identifying the cause of the condition may be challenging. Figure 1 outlines guidelines on differentiating between chronic, hospital-induced constipation and trauma-induced or trauma-associated constipation.7 A diagnosis of constipation is mainly based on the patient’s medical and surgical history and a thorough physical examination. Important factors to consider include the patient’s prehospital comorbidities; medications; reason for hospitalization; dietary habits, including fluid and fiber intake; baseline bowel function; and physical activity level. An abdominal and digital rectal examination must be performed if there are no contraindications (ie, severely neutropenic patients and patients with prostatic abscesses or prostatitis).8 Symptoms such as weight loss, anemia, abdominal distension, abdominal masses, and a palpable colon should be ruled out when making the diagnosis. Abdominal distension, decreased or even increased bowel sounds from partial obstruction, and a left lower quadrant “mass” from fecaliths are not uncommon and should also be considered. The perineum should be examined for hemorrhoids, fissures, rectal prolapses, and skin tags. Anal wink reflex can be elicited using a cotton-tipped applicator or cotton pad in all four quadrants around the anus. The absence of anal contraction may indicate sacral nerve pathology.9 Digital rectal examination is necessary to help assess the resting sphincter tone, check the walls of the rectum for masses, identify anal fissures, and check for impacted feces.10 Laboratory and ancillary testing for electrolyte, blood glucose, and creatinine abnormalities; thyroid function tests; and radiographic and endoscopic evaluations may be necessary in some cases based on clinical suspicion of secondary causes of constipation.10

According to guidelines published by the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, red flags that should prompt consideration of a colonoscopy include hematochezia, unintended weight loss, obstructive symptoms, a family history of colon cancer, iron-deficiency anemia, a positive fecal occult blood test, and acute onset of constipation in a patient older than 50 years with no previous colorectal cancer screening.11 Even if colon cancer is not suspected, this is an excellent time to review whether the patient has had age-appropriate colon cancer screening and, if he or she has not had it, to arrange for the screening following hospital discharge.11 In the following sections, we review several pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies to help prevent and treat constipation in the hospitalized older patient.

Nonpharmacologic Prevention and Management of Constipation

Educating patients about various causes of constipation that they may be able to control, such as diet, is highly encouraged in the prevention and management of constipated adults.12 The best way to prevent and treat constipation is to make sure that the older patient is getting sufficient quantities of fluid and fiber in his or her diet.13 By doing this, the stool bulk is increased and the stool becomes softer, enabling it to move through the intestines more easily. There is a paucity of clinical information on the actual quantity of fiber necessary for optimal bowel function, but the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommends that after age 50 years, women receive around 21 g of dietary fiber daily and men receive around 30 g daily14; however, even small amounts of fiber may be beneficial. Starting with lower amounts of fiber and increasing over time may improve tolerability. Prunes, apples, and whole grains are just a few examples of high-fiber foods. A discussion of fiber supplements is provided later in this article.

Exercise is also considered a natural remedy to help regulate the hospitalized older patient’s bowel function. One cannot overemphasize the importance of early ambulation after surgery and hence the role of physical and occupational therapists and good nursing care. Many physicians advise that exercising after meals may prevent or reduce constipation by increasing blood flow to the stomach and lessening the time it takes for food to travel through the body, thereby limiting how much water the body absorbs from the stool.15 However, there is a paucity of data examining the relationship between exercise and constipation, particularly with regard to the intensity and frequency of exercise, indicating that this is an area where further studies are warranted.16

There are also numerous ways to help prevent and improve constipation in the hospitalized older patient by establishing a bowel regimen that is easy and comfortable. This includes having timed toilet training, especially for those persons unable to reach the bathroom unassisted because of their medical problems, such as severe arthritis, ambulatory dysfunction, deconditioning, extremity or pelvic fractures, and dementia. A bedside commode should be encouraged as much as possible if the patient cannot go to the bathroom unaided. Early removal of nasogastric tubes, Foley catheters, and restraints can also facilitate a regular bowel regimen, enabling early ambulation and use of a toilet. Although sometimes difficult to achieve in the hospital setting, there is still a need to help create a quiet and private environment for patients to feel comfortable having bowel movements. Bed pans are usually uncomfortable for most patients and may affect the desire to have bowel movements or may present psychological barriers. Physicians can also prevent postoperative constipation by paying attention to bowel stimulation and avoiding use of narcotics (if possible), as these may cause constipation.

Pharmacologic Prevention and Management of Constipation

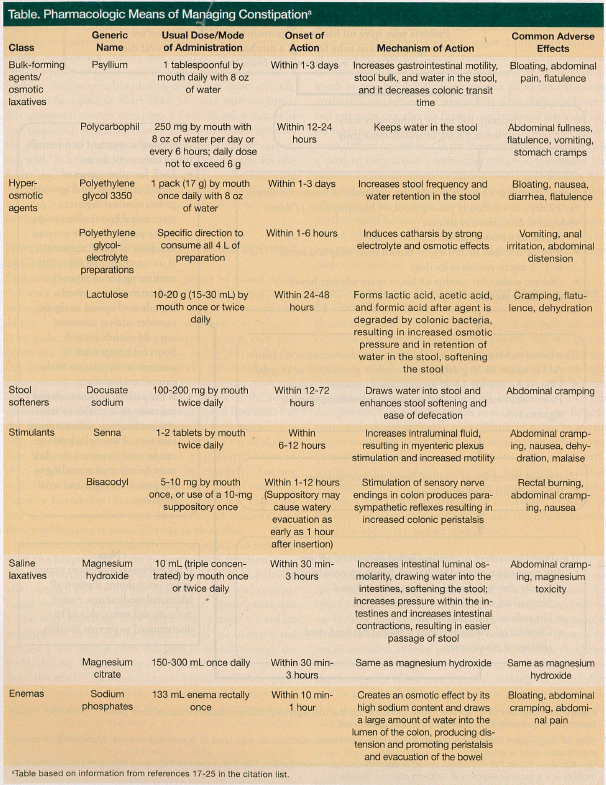

Depending on the underlying etiology of the patient’s constipation, the severity of the constipation, and the persistence of the problem after having tried nonpharmacologic measures, physicians may have to resort to pharmacologic treatment. Figure 2 provides a representative guideline for the pharmacologic management of constipation in acute care geriatric patients.7 In certain situations, one can be proactive and administer medications prophylactically to ensure proper bowel function. There are several pharmacologic options for the treatment of constipation. A list of the various medications available, along with their dosage, mode of administration, onset of action, mechanism of action, and common side effects, is depicted in the Table.17-25 Some of the more commonly used laxatives and the role of enemas are discussed in the section that follows.

Bulk-Forming Laxatives

Bulk-forming agents, also known as fiber supplements, are the most commonly recommended initial treatments for constipation. They are considered the safest laxatives to use because they can be used long-term to maintain regular bowel movements.17 Bulk-forming laxatives help increase fiber in the colon, thereby increasing bulk, an effect that helps induce movement of the intestines. It also works by increasing the amount of water in the stool, making the stool softer and easier to pass. There are two forms of dietary fiber available in the United States: soluble and insoluble. There are also numerous different types (eg, psyllium, polycarbophil, guar gum, malt soup extract) and many different brands of these fiber supplements.

Some people may develop gas with the use of bulk-forming laxatives, but this usually only occurs if too much is taken too quickly. The gas will become less problematic as the body adjusts to the extra fiber. In addition, sufficient water must accompany psyllium intake to prevent the solution from becoming too viscous, which can lead to intestinal obstruction. In general, each dose of a bulk-forming laxative should be taken with an 8-oz glass of fluid (eg, water or juice). Some of these agents, such as psyllium, come in the form of a capsule, liquid, or wafer.18

It may take 1 to 3 days before a bulk-forming laxative starts to work, and patients should be advised to take this medication regularly to experience maximum benefit. Additionally, bulk-forming agents can decrease the absorption of other medications, particularly aspirin, warfarin, and carbamazepine, which are frequently taken by older adults, and may also affect blood glucose levels, so physicians should be aware of a patient’s comorbidities and medication regimen before recommending use of a bulk-forming laxative.17

Hyperosmotic Laxatives

Examples of hyperosmotic agents include polyethylene glycol 3350 and lactulose. These agents are also referred to as oral osmotic agents because they work by drawing water into the colon from surrounding body tissues, making the stool softer and, as a result, easing the passage of stool. Caution is advised when using these agents in the elders, however, as these patients may be more sensitive to their side effects, especially diarrhea, which may lead to dehydration.19

Stimulant Laxatives

Stimulant laxatives, the most powerful type of laxative, induce increased colonic motility and ease of defecation by stimulating the myenteric plexus and promoting accumulation of water and electrolytes in the colon. Long-term use of stimulant laxatives is not recommended because these medications may change the tone and sensation in the colon and may increase the likelihood of dependence.20 Senna and bisacodyl are two examples of stimulant laxatives. These laxatives are often taken as a tablet by mouth, but senna also comes in powder, liquid, and granular formulations.

Stool Softeners

Stool softeners, also called emollient laxatives, work by enhancing the incorporation of water, moisture, and fat into the stool, increasing bulk, stool softening, and lubrication. The active ingredients in most stool softeners are docusate and sennosides. Stool softeners are used more to prevent constipation than to treat it, as they enable patients to have a bowel movement without straining, which is recommended in those recovering from a myocardial infarction, those with high blood pressure, and those with abdominal hernias or painful hemorrhoids.17 Stool softeners are generally safe and well tolerated by most older patients; however, combining them with a lubricant laxative mineral oil (discussed in the next section) is not advised because the stool softener may increase the absorption and toxicity of the lubricant. Additonally, inflammation in the lymph glands, spleen, and liver may result if mineral oil droplets are absorbed and deposited into the body.17 It should be noted that, because stool softeners do not increase bowel activity itself, their use may result in certain individuals having a bowel filled with soft stool.

Lubricant Laxatives

As the name suggests, lubricant laxatives work by lubricating the colon. They also coat and soften stool, facilitating its passage. Mineral oil (ie, liquid petrolatum) is one of the most commonly prescribed lubricants to manage constipation. There are many precautions that should be taken when using lubricant laxatives. Mineral oil, for example, should be avoided in patients on blood thinners, such as warfarin, because the lubricant decreases the absorption of vitamin K from the intestines; the decreased absorption of vitamin K in such patients can potentially lead to “over-thinning” of the blood and an increased risk of excessive bleeding.17 In addition, mineral oil may cause pneumonia (lipoid pneumonia) if it gets aspirated into the lungs. Some individuals, such as elders, patients who have had a stroke, and those with swallowing difficulties, are prone to aspirate, especially when in the supine position; therefore, mineral oil given by mouth should be avoided as much as possible.17 Because a significant absorption of mineral oil into the body can occur if used over prolonged periods, mineral oil should only be taken on a short-term basis. As noted previously, mineral oil may be problematic when used with stool softeners. A relatively safe way to use mineral oil is with retention enemas, which helps lubricate and facilitate the passage of stool in the distal colon, a common area for fecal impaction.

Saline Laxatives

The active ingredients in saline laxatives are mostly magnesium, sulfate, citrate, and phosphate ions. The mechanism of action of these ions involves increasing intestinal luminal osmolarity, causing water to be drawn into the intestines. This water softens the stool, increases pressure within the intestines, and increases intestinal contractions, enabling easier evacuation of stool.17 Some examples of saline laxatives are magnesium sulfate, magnesium hydroxide, and magnesium citrate.

It is recommended that oral doses of saline laxatives be taken with one to two glasses of water. The onset of bowel response is usually 30 minutes to 3 hours after administration. Saline laxatives containing magnesium or phosphate salts should not be used in individuals with impaired kidney function, as there may be some absorption of the active ingredients from the intestines into the blood circulation.17 Excess accumulation of these ingredients in the blood can lead to toxicity. Use of laxatives that contain high amounts of sodium is also contraindicated in patients who need to limit their sodium intake, such as those with congestive heart failure, hypertension, and kidney disease.

Enemas

Generally, an enema refers to a solution that is administered into the rectum to facilitate the evacuation of feces, but it is also used as a way to introduce nutrients to the body or to instill substances that help visualize the lower gastrointestinal tract during a radiological examination.21 Enemas are intended to be used occasionally, not regularly, and they are often employed as a last resort for the treatment of constipation. This is because chronic, excessive use of enemas can result in megacolon or disturbances of the fluids and electrolytes in the body, the latter of which is especially true of tap water enemas (these are also often referred to as soapsuds enemas).22 There are many different types of enemas in addition to tap water enemas, including saline enemas, phosphate enemas, mineral oil enemas, and emollient enemas, each of which promotes stool evacuation via a different mechanism of action. For example, phosphate enemas, which contain sodium acid phosphate and sodium phosphate, stimulate rectal motility and increase the water content of the stool23; whereas mineral oil enemas and emollient enemas (eg, docusate) work to lubricate and soften hard stool.24 Tap water enemas are not recommended because they can produce mucosal damage to the rectum.25

Enemas may be useful when there is an impaction or a hardening of stool in the rectum, however, sometimes they are not able to entirely remove a blockage. Even after an enema and manual removal of impacted stool, it may be helpful to use colonic cleansing with polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solutions to remove proximal colonic stool collections.25 To have maximum efficacy, the instructions that are provided with the enema must be closely followed. This requires thoroughly explaining the procedure to the patient and careful administration of the solution, ensuring the patient is properly positioned to receive and retain the full enema.21 Defecation usually occurs within a few minutes to 1 hour after administration of the enema.

Conclusion

Constipation is commonly encountered in older adults, as these individuals are especially susceptible to chronic physiologic and pathologic changes that can predispose them to constipation. In addition, many older persons take multiple medications that can cause or contribute to constipation. Older people are also at high risk for potentially serious constipation-related complications, which can compromise their quality of life and impose a financial burden from the added use of medications and other associated healthcare costs. Identifying the underlying causes of constipation is important to ensure that appropriate treatment is initiated. Secondary causes of constipation can best be managed by correcting the underlying causes and predisposing factors. Primary constipation is usually resolvable with sequential adjustments to diet, the provision of patient education and training, and the use of as-needed laxatives and enemas. Some refractory cases, such as those resulting from mechanical intestinal obstruction, may warrant surgery.

References

1. Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(14):1360-1368.

2. O’Keefe EA, Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Jacobsen SJ. Bowel disorders impair functional status and quality of life in the elderly: a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(4):M184-M189.

3. Chang L. Review article: epidemiology and quality of life in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(suppl 7):31-39.

4. Irvine EJ, Ferrazzi S, Pare P, Thompson WG, Rance L. Health-related quality of life in functional GI disorders: focus on constipation and resource utilization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(8):1986-1993.

5. Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34(4):606-611.

6. Singh G, Lingala V, Wang H, et al. Use of healthcare resources and cost of care for adults with constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(9):1053-1058.

7. Geriatric guidelines: Constipation. R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, MD. Available upon request from the authors.

8. Ylitalo AW. Digital rectal examination. Medscape Reference. Updated February 29, 2012. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1948001-overview#aw2aab6b2b3. Accessed September 7, 2012.

9. Jamshed N, Lee Z-E, Olden KW. Diagnostic approach to chronic constipation in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(3):299-306.

10. Constipation diagnostic tests. Best Practice BMJ Website. http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/154/diagnosis/tests.html. Accessed September 11, 2012.

11. Qureshi W, Adler DG, Davila RE, et al. ASGE guideline: guideline on the use of endoscopy in the management of constipation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(2):199-201.

12. Spruill WJ, Wade WE. Diarrhea, constipation, and irritable bowel syndrome. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2008:617-632.

13. Basson MD. Constipation treatment and management. Dietary measures. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/184704-treatment#aw2aab6b6b2. Updated August 31, 2012. Accessed September 11, 2012.

14. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Fiber. www.eatright.org/Public/content.aspx?id=6796#.UE-DUOYmy_M. Accessed September 11, 2012.

15. Exercise to ease constipation. WebMD. www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/exercise-curing-constipation-via-movement. Accessed September 11, 2012.

16. Beradze G, Sherozia M, Shankulashvili G. Influence of an exercise therapy on primary chronic constipation [in Russian]. Georgian Med News. 2011;198:29-32.

17. Cunha JP. Laxatives for constipation. MedicineNet. www.medicinenet.com/laxatives_for_constipation/page4.htm#bulk-forming_laxatives. Published 2011. Accessed September 11, 2012.

18. Psyllium. Medline Plus. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a601104.html. Accessed September 11, 2012.

19. Mayo Clinic. Over-the-counter laxatives for constipation: use with caution. www.mayoclinic.com/health/laxatives/HQ00088. Published April 23, 2011. Accessed September 12, 2012.

20. Senna. Medline Plus. Updated November 15, 2011. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a601112.html. Accessed September 12, 2012.

21. Enema. The Free Medical Dictionary. http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/enema. Accessed September 12, 2012.

22. Marks JW. Constipation. What treatments are available for constipation? MedicineNet. www.medicinenet.com/constipation/page6.htm. Accessed September 12, 2012.

23. Davies C. The use of phosphate enemas in the treatent of constipation. Nursing Times. 2004;100(18):32. www.nursingtimes.net/the-use-of-phosphate-enemas-in-the-treatment-of-constipation/204306.article. Accessed September 12, 2012.

24. Mineral oil. Drugs.com. www.drugs.com/mtm/mineral-oil-rectal.html. Accessed September 12, 2012.

25. Beers MH, Berkow R, eds. Constipation, diarrhea, and fecal incontinence. In: The Merck Manual of Geriatrics.3rd ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories; 2000:1085.

Disclosures:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to:

Steven R. Gambert, MD, AGSF, MACP

University of Maryland Medical Center N3E09, 22 S. Greene Street

Baltimore, MD 21201