Contextual Factors Influencing Level of Care Decisions for Geriatric Patients

Introduction

Studies have shown that older adults strongly prefer to continue living in their own homes, also known as aging in place.1,2 Premature admission to a nursing home can have devastating consequences for patients, families, and society. A consequence for the older patient is unnecessary loss of independence; however, an overly autonomous care setting may lead to diminished quality of life for the patient and his or her family caregivers, stemming from an inability to meet care needs.3 In addition, nursing home placement results in a high cost to society, as publically financed programs such as Medicaid largely absorb the cost of such care. For example, the House Democrats of Connecticut have determined that reducing the frequency of inappropriate nursing home placements in Connecticut alone could reduce societal and governmental costs by as much as $3.8 million in fiscal year 2010.4

Given the significant impact on quality of life for older adults and families, combined with the national focus on curbing healthcare costs, it is critical that physicians make accurate and nuanced decisions about level of care. Simple tools to clarify clinical decisions and simple, straightforward explanations to families about these decisions are needed. Unfortunately, however, there is a lack of standard best practices in the industry and across the United States.3

Often, a less restrictive level of care (remaining in the community with additional services or an assisted living facility) may be more appropriate, beneficial, and cost-effective. Yet, many physicians who make these determinations are family physicians or internists with no specialized training in the care of elderly patients, including those residing in nursing homes.5 In the years to come, family physicians and internists will become increasingly responsible for the care of geriatric patients given demographic shifts in world aging6 combined with a well-documented dearth of trained geriatricians.7 Less than 1% of physicians had completed a geriatric fellowship in 20045; however, even geriatric fellowship training may not emphasize nursing home care.5

This article distinguishes factors influencing “nursing facility clinical eligibility” (NFCE) from decisions about nursing home placement for geriatric patients, and reviews the following aspects of level of care decision-making: decision-making criteria; clinical assessment; functional considerations; and types of support that allow patients with NFCE to remain in the community. The financial context is also discussed, and recommendations about further research and training are offered.

Challenging Decisions

It can be challenging for physicians who are not trained or experienced in geriatric care to make level of care decisions. On average, older adults have between 2 and 3 chronic medical conditions by age 75, and some have up to 10 or 12 conditions.8 Twenty percent of the Medicare population has at least 5 chronic conditions, accounting for two-thirds of total program spending.9 Geriatric patients present complex clinical profiles, and their medical, psychological, and social needs often shift.10 Treatment of most chronic conditions requires a broad set of health and supportive services. These services span assessment, diagnosis, prevention of exacerbations, rehabilitation, and monitoring, and are often provided by different clinicians and nonclinical supports over a long period of time. These services can be vital to maintain health, slow decline, and mitigate the impact of the condition on the patient’s life.11 The ways in which our current healthcare system is poorly equipped to meet the needs of many patients who require treatment of chronic illness are well documented.12

Multiple Decisions—Multiple Ramifications

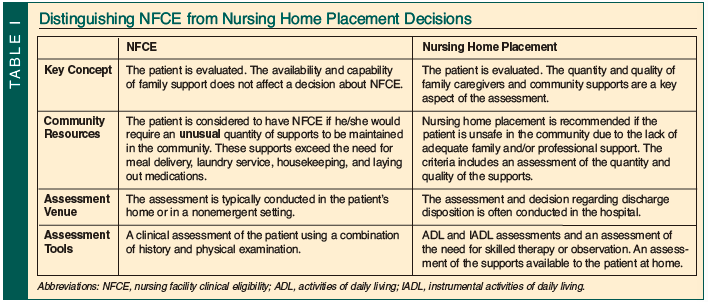

Physicians are often asked to evaluate patients to determine whether they have NFCE. In practice, recommendations are based on several clinical assessments and nonclinical considerations. Although it would initially appear that a decision about NFCE would be the same as one regarding nursing home placement, they are actually quite different (Table I). A patient who needs nursing home placement will certainly have NFCE; however, a patient may have NFCE but not require nursing home placement because of supports available to him or her. Nursing home placement is based on the availability of community resources and the competence of family caregivers. NFCE, on the other hand, is based entirely on the patient’s functional abilities, medical condition(s), and cognitive state.

Each decision carries different ramifications. In many states, community resources are rationed based on level of care decisions. NFCE assessment may, in fact, allow the marshalling of resources that can prevent nursing home placement. Admission to adult day care, for example, often requires that the individual be assessed to have NFCE. Similarly, some home care services are available to exclusively individuals who have NFCE and are unavailable to other patients. In some states, there may be waiting lists for a variety of services that are much shorter for those persons who are assessed as having NFCE.

Decision-making Criteria for NFCE

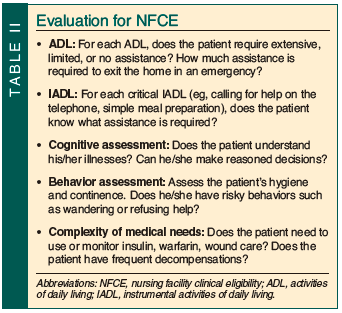

Although assessments regarding the need for nursing home placement are frequently done in the hospital, level of care assessments for admission to community programs are usually performed in the patient’s home. Level of care assessments are also done in continuing care retirement communities to determine whether a change is needed from independent living to assisted living or to skilled care. In assessing level of care, a key concept is safety within the context of the community. Could the patient survive safely without unusual supports? The assessment includes collecting information about preexisting conditions, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, patient safety, activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) function, cognitive function, and continence.

It is sometimes necessary to defend an assessment, as there may be conflicting opinions, either against another physician’s assessment or against an appeal from the patient or his or her family; this can occur in the office or in court. In this context, physicians must be able to explain assessments in ways that are easily understood by nonspecialists.

Physicians assess the patient’s ability to respond to potential problems. Can the patient contact help if needed? Does the patient know what to do in the event of likely medical problems (eg, can a person with diabetes competently handle needed medications)? These issues are usually addressed by asking the patient how he or she would respond to hypothetical situations. In some cases, the physician will ask the patient to dial a telephone or demonstrate on an actual piece of equipment (for example, a nebulizer or a blood glucose monitor) his or her ability to react to certain situations such as an emergency. A demonstration will clarify functional competency, which can be difficult to measure just by talking to a patient. Although the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) does not directly address functional issues, it is a baseline screening test for cognitive status and is frequently requested by adjudicators.

Decision-making capacity needs to be assessed in the context of those decisions that the patient may need to make if he or she is living independently at home. For example, the patient should be able to describe how to decide whether to allow someone into the home. The patient should also be able to give a reasonable description of some of the burdens of living at home or in another placement, and explain why one is preferred over the other. These explanations do not need to be complete or entirely correct, but they do have to be free of delusions and show some logical thought processes.

Similarly, ADL assessment includes the patient’s ability to get food from storage (typically a kitchen cabinet, refrigerator, or freezer) into his or her stomach. Although a physician cannot usually watch this happen, he or she can look at the food available and question the patient about the preparation.

Hygiene and continence is assessed by a combination of questioning and the assessment of the patient’s clothing and living space. If the patient is currently receiving considerable help with bathing and dressing, then the fact that he or she is clean and well groomed may not be evidence of personal ability. On the other hand, assistance from an aide only 2 or 3 times per week, without assistance from family caregivers, would still require enough personal participation to indicate that the patient can handle hygiene adequately.

Mobility needs are affected by the patient’s location. Someone with impaired mobility is likely to find it much easier to exit from a wheelchair-accessible apartment than from the second floor of a family home. Since changes in living space are often difficult to achieve because of a lack of available options, this is one factor where the criteria for decisions must take into account more than just the patient’s ability.

The complexity of medical needs has a role. Is the patient able to take prescribed medications reliably and safely? A simple medication program for hyperlipidemia takes much less patient competence than one for insulin-dependent diabetes. Some medications can be missed (or doubled) without great danger (eg, lipid medications, osteoporosis medications), while others can lead to serious complications if omitted or overused (eg, insulin, warfarin, digoxin). The need for  someone to lay out medications is not an indication of NFCE, but if the patient needs immediate oversight to ensure that the medication is taken as prescribed, then NFCE would be indicated.

someone to lay out medications is not an indication of NFCE, but if the patient needs immediate oversight to ensure that the medication is taken as prescribed, then NFCE would be indicated.

Finally, a history of frequent need for emergency department assessments or calls to emergency medical technicians may be an indication that the patient requires more monitoring than he or she has received, and is often an indication that the patient has NFCE (Table II).

Supports that Help Patients with NFCE Remain in the Community

The availability of community supports, such as care management (provided by a professional, often a social worker, who supervises the care, arranges medical appointments, and so on, often when family members live far away), Meals on Wheels, adult day centers, senior centers, friendly visiting services, and transportation services, has only a small impact on assessing NFCE. Although in practice it is impossible to completely separate a patient from the immediate community and family supports, the goal of a level of care assessment is to assess the patient, not the availability and quality of the supports. On the other hand, when assessing the need for nursing home placement, the supports play a major role.

Family Caregivers

In addition to community resources, the availability and competence of family caregivers is particularly significant in nursing home placement decisions. Unpaid family caregivers have emerged as an important resource to older adults and to society. According to a national survey conducted by the National Alliance for Caregiving and the AARP, 54 million Americans (23.5% of the adult population) are family caregivers, defined as individuals over age 18 who provide unpaid care for individuals over age 18.13 While the actual cost of care provided by family members is unpaid, the midrange value of family caregiver contributions has been estimated at $257 billion annually.12

Telehealth Innovations

Recent innovations in home-based technology have ushered the new field of telehealth, which differs from the more widely known telemedicine. Telehealth involves mainly technology to monitor and support patients in their residences, while telemedicine technology typically allows a physician at a remote site (possibly a few miles away in a city or much farther, perhaps in another state) to examine and even perform procedures on a patient in an office, clinic, or operating room. The salient technologies for telehealth are typically comprised of various sensors, interactive communication devices, and cameras connected to computers both inside and outside of the home, making it possible to monitor the activity of older persons living in the community. Some telehealth technologies have the capability to support and maximize the functioning of older adults by providing corrective feedback when mistakes in routine are made, providing reminders for medication, assisting with locating objects and remembering actions already taken, stimulating brain function, and connecting to relatives and support networks.2,14

Some fears of telehealth include losing independence and privacy; however, these fears are balanced by the prospect of continued community dwelling and quick connection to working caregivers or emergency assistance. Elderly persons benefit from the freedom to maintain normalcy and independence, while having the added security of available support.1,2

The use of technology to keep patients at a lower level of care, typically at home, has only recently entered the decision-making matrix. The British Geriatrics Society, among other organizations, identifies a critical need for medical education and clinical research in home care, most specifically, comprehensive education for practicing physicians in home care–related technology.15 Physician understanding regarding the ways in which telehealth technology can increase independence and improve the quality of life of community-dwelling elderly patients is a critical precursor to physician acceptance. Such acceptance is necessary prior to the widespread consideration of telehealth technology in placement decisions.16

Healthcare Financing—Cost Is a Consideration

Decisions about level of care occur in the context of healthcare costs. Elder care assumed nearly 70% of healthcare spending in the United States in 2009.17 This will grow given population aging trends. Medicaid is the most significant payor for long-term care services, which has historically meant care in a nursing home. Cost containment goals and consumer preference have caused states to shift the public financing of long-term care services away from institutional-based care to community-based care.18

The majority of spending for Medicaid-financed community-based services is through Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) waiver programs, also known as 1915(c) or HCBS waivers. These allow states to waive certain federal requirements and to provide community-based services to individuals who otherwise would require institutional care.19 It must be confirmed by state Medicaid programs that individuals who are seeking waiver services meet the requirement for a “nursing facility level-of-care.”18 Each state determines its own “level-of-care” criteria,20 and physicians play a significant role in interpreting that criteria. The “budget neutrality requirement,” which mandates that federal costs for HCBS waiver services not be higher than the cost of institutionalized services, has been a driving force in the design of Medicaid HCBS waiver service programs.18

The increasing weight of consumer preference also merits consideration. States are increasingly involving consumers in care planning.20 As of 2006, 22 states reported turning to individual budgeting for clients, such as the Cash and Counseling and the Money Follows the Person programs.19 It has yet to be determined how physician decisions intersect with the formal inclusion of consumer preferences.

Conclusions and Future Investigation

Clinical decisions about appropriate level of care for geriatric patients are distinct from decisions about nursing home placement. Physician decision-making about NFCE rests solely with clinical evaluation of the patient. The context for nursing home placement decisions is multifactorial, including consideration of home and community-based resources and the competence of family caregivers. Telehealth and other technology options can also be explored in various communities. The cost impact of physician decisions regarding NFCE on the family and the healthcare system, and the impact of consumer preference, also bear recognition.

Recommendations for future investigation include comparisons of placement decisions made by physicians with and without geriatric training and consequent healthcare costs. Physician awareness and acceptance of home-based technology for geriatric patients requires additional research. Finally, the development of models for improved coordination of the clinical team with patient preference, community supports, and family caregivers merits further investigation.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Grant is Chair, and Ms. Fey is Geriatric Nurse Practitioner, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Albert Einstein Healthcare Network, Philadelphia, PA; Ms. Fedus is Gerontologist & Coordinator of Elder Programs, The Consultation Center, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT; and Dr. Campbell is Lecturer, Graduate School of Social Work and Social Research, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA.

References

1. NAHB Research Center. The national older adult housing survey. A secondary analysis of findings. http://www.toolbase.org/PDF/CaseStudies/NOAHSecondaryAnalysis.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2010.

2. Rogers WA, Fisk AD. Psychological science and intelligent home technology: Supporting functional independence of older adults. Psychological Science Agenda 2004;18(2). http://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2004/02/rogers.aspx. Accessed October 18, 2010.

3. Ashcraft AS, Owen DC, Feng D. A comparison of cognitive and functional care differences in four long-term care settings. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7(2):96-101.

4. House Democrats of Connecticut. A balanced budget for Connecticut. http://www.housedems.ct.gov/Budget/Appropriations.asp. Accessed October 18, 2010.

5. Levy C, Epstein A, Landry L, Kramer A, Harvell J, Liggins C; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. Literature review and synthesis of physician practices in nursing homes. October 17, 2005. http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/phypraclr.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2010.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in aging—United States and worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52(6):101-104, 106.

7. Butler RN. Redesigning health care for an older America. In: The Longevity Revolution: The Benefits and Challenges of Living a Long Life. New York: Public Affairs; 2008:216-219.

8. Wolff J, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2002;162(20):2269-2276.

9. Partnership for Solutions. Medicare: Cost and prevalence of chronic conditions. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. 2002. http://www.partnershipforsolutions.org/DMS/files/Medicare_fact_sheet.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2010.

10. Bernabei R, Landi F, Onder G, Liperoti R, Gambassi G. Second and third generation assessment instruments: The birth of standardization in geriatric care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63(3):308-313.

11. Kane RL, Priester R, Totten A. The right health care workers with the right skills. In: Meeting the Challenge of Chronic Illness. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005:91-120.

12. Arno P. Economic value of informal caregiving: 2000. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry; February 24, 2002; Orlando, FL.

13. National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. Caregiving in the U.S., funded by MetLife Foundation. 2009. http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2010.

14. Magnusson L, Hanson E, Borg M. A literature review study of information and communication technology as a support for frail older people living at home and their family carers. Technology and Disability 2004;16(4):223-235.< p> 15. British Geriatrics Society. Telehealth and Telecare - Best Practice Guide. http://www.bgs.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=646:gpgtelecare&catid=12:goodpractice&Itemid=106. Accessed November 23, 2010.

16. Chau PY, Hu PJ. Investigating healthcare professionals’ decisions to accept telemedicine technology: An empirical test of competing theories. Information & Management 2002;39(4):297-311.

17. Bendixen RM, Levy CE, Olive ES, Kobb RF, Mann WC. Cost effectiveness of a telerehabilitation program to support chronically ill and disabled elders in their homes. Telemedicine J E-Health 2009;15(1):31-38.

18. Summer L. Community-based long-term services financed by Medicaid. Managing resources to provide appropriate Medicaid services. Georgetown University Long-Term Care Financing Project. 2007. http://ltc.georgetown.edu/pdfs/summer0607.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2010.

19. Spillman BC, Black KJ, Ormond BA; Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Beyond cash and counseling: An inventory of individual budget-based community long term care programs for the elderly. April 2006. http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/7485.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2010.

20. Gillespie J; Rutgers Center for State Health Policy and National Academy for State Health Policy. Assessment instruments in 12 states. January 2005. http://www.hcbs.org/moreInfo.php/state/177/doc/844/Assessment_Instruments_in_Twelve_States. Accessed October 18, 2010.