Depression in a Patient with Alzheimer’s Disease

Case Presentation

Mrs. D is an 85-year-old widowed woman who resides with her granddaughter, Ms. S. Mrs. D was diagnosed with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type 8 months ago and is currently being treated with donepezil 10 mg daily. She also has hypertension, coronary artery disease, and osteoarthritis. Her other medications include losartan 50 mg daily, aspirin 81 mg daily, and acetaminophen 650 mg 3 times daily. Mrs. D receives 4 hours daily of home attendant services 5 days per week. Ms. S moved in with her 6 months ago to help with her care. Mrs. D raised her granddaughter after her mother was sent to prison for drug-related crimes. Ms. S is very devoted to her grandmother, but works long hours as an event planner.

Mrs. D has had a relatively stable course since her dementia was diagnosed, with clear impairments in recent memory, word finding, and difficulty with dressing and preparing meals. She has been accepting help from her home attendant and has been going outside for a daily walk. Mrs. D was able to tolerate being alone after her aide left, and she ate the food prepared for her. Ms. S begins to notice that when she comes home from work, her grandmother is asleep in front of the television, and several times per week she has not eaten her breakfast or dinner. Ms. S leaves notes for the home attendant to place the food out where Mrs. D can find it easily.

Mrs. D is becoming tearful each morning when her granddaughter leaves for work. Ms. S stays later some mornings until the aide arrives but cannot do this very often. She continues to find that her grandmother is not eating meals and encourages Mrs. D to have a snack with her. She also notices that Mrs. D is often awake most of the night, quiet but pacing in the apartment. Mrs. D’s crying spells appear to be increasing, and she often sits by herself in the dark. Ms. S feels terrible and tries hiring an additional aide to help her grandmother.

The new aide is able to get Mrs. D to eat more and takes her to her primary care physician. No new medical problems are identified, and the results of lab tests including a complete blood count, chemistry panel, thyroid profile, vitamin B12, and folate levels are all within normal limits. Mrs. D has lost four pounds since her last appointment 4 months ago. The doctor suggests that Mrs. D take a multivitamin and a nutritional supplement to help her maintain her weight, which has always been on the low end of the ideal range for her height. He also states that she “looks depressed” and suggests a psychiatric evaluation. Ms. S feels desperate to help her grandmother and arranges to take time off from work to attend the psychiatry appointment.

Discussion

Depressive features are relatively common among patients who have dementia.1 Up to 45% of patients with dementia display depressive symptoms that cause distress during the course of their illness.1-3 Depression in a patient with dementia results in an increase in behavioral disturbances, subjective distress, and premature decline in functional status.2 Caregiver burden increases significantly when depressive symptoms occur. There is also an increased rate of depression among caregivers who are dealing with the needs of a patient who has both dementia and depression.2-5

Depression among patients with dementia is often difficult to assess due to the fluctuating course of the symptoms and the simultaneous occurrence of additional symptoms such as irritability, agitation, anxiety, and impulsivity.3-5 Loss of verbal and communication skills makes it difficult for family, caregivers, and professionals to gain understanding of the patient’s thoughts and feelings.2 The clinician must maintain a high index of suspicion that depression is an issue when a patient with dementia presents with behavioral changes, loss of function, and changes in sleep or appetite.3

Several screening and assessment instruments have been used to identify depression in dementia, including the Geriatric Depression Scale, the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia, and the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale.2-4 While these assessment tools are valuable, many clinicians find using clinical criteria and symptom-based checklists to be more helpful.2 It is also vital that the clinician inquire directly about any suicidal behaviors or expressions. While suicide is less common among patients with dementia, any dangerous or suicidal behavior may require hospitalization for safety and stabilization.2-4

The National Institute of Mental Health has identified provisional criteria of depression in Alzheimer’s disease that emphasizes a change or disturbance in affect, including depression, irritability, anxiety, or euphoria that creates a disruption in the patient’s well-being or ability to receive care.6 The mood changes must be present for at least 2 weeks and are often associated with agitation, aggression, and sleep and appetite disturbance. Using these criteria, more cases are identified than if Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision criteria or traditional rating scales alone are utilized.4-6

The National Institute of Mental Health has identified provisional criteria of depression in Alzheimer’s disease that emphasizes a change or disturbance in affect, including depression, irritability, anxiety, or euphoria that creates a disruption in the patient’s well-being or ability to receive care.6 The mood changes must be present for at least 2 weeks and are often associated with agitation, aggression, and sleep and appetite disturbance. Using these criteria, more cases are identified than if Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision criteria or traditional rating scales alone are utilized.4-6

These criteria have focused on dementia of the Alzheimer type. Patients who have other types of dementia including vascular, frontotemporal, and Parkinson’s disease–related dementia also have depression.1,2 Criteria specific to these dementias have not been devised, but clinical evaluation and attention to mood changes should alert the clinician to new-onset depression.

Treatment of depression in dementia must address the psychosocial, behavioral, environmental, caregiver, and biological needs of the patient. Many clinicians suggest a trial of behavioral interventions before medication is considered2,7 (Table I). In all cases, nonpharmacological interventions should be utilized as either primary or adjunctive to medication.2 Caregiver education is a vital element to the care of the patient with depression and dementia, and referral to local support groups and the Alzheimer’s Association is often helpful.

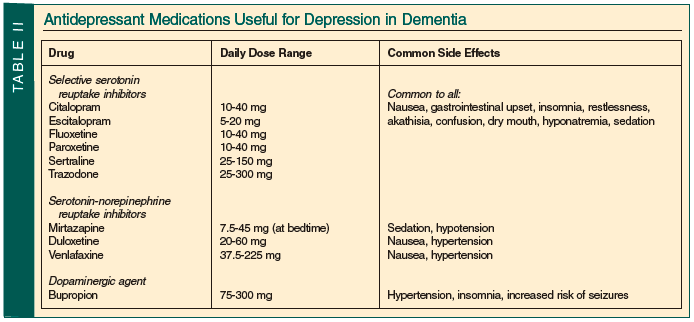

Antidepressant medications have been successfully used to treat depression in dementia2,8,9 (Table II). It is very important to recognize the higher incidence of side effects and drug-drug interactions that occur among patients with dementia.2 All antidepressants may worsen confusion and cause a decline in memory and functional status.8,9 The family or caregiver should be instructed to monitor for side effects, and the clinician may need to discontinue the medication and consider an alternative drug. Dose adjustments should be made slowly but regularly until clinical improvement is reached. A significant number of patients with dementia are maintained on very low doses of antidepressants that are clinically subtherapeutic.8 Another common error is the use of sedatives or antipsychotic agents to treat the behavioral disturbance rather than addressing the key mood symptoms.2 Polypharmacy with psychotropic agents should be avoided, as the risk of adverse events increases with no clear benefit for this practice among patients with dementia.2,8

Information regarding the psychiatric symptoms related to dementia may be downloaded from the Alzheimer’s Association website at www.alz.org and the Geriatric Mental Health Foundation website at www.gmhfonline.org.

Outcome of the Case Patient

Ms. S brought her grandmother to the psychiatrist. Mrs. D appeared distressed and was clutching tissues tightly in her hands throughout the interview. She appeared thin but had not lost any more weight. Ms. S described her grandmother as a previously happy woman who seemed to have lost interest in everything. Mrs. D used to look at family photos and tell stories, but has stopped looking at the pictures. She cried almost every day and was staying up most of the night. Ms. S appeared tired, stating that she felt unable to sleep with her grandmother awake during the night. Mrs. D stated that she “felt bad” and frequently asked during the appointment to go home. She denied any suicidal ideation, stating that “God will know when it is my time.” Mrs. D appeared depressed, worried, and anxious, with reduced sleep, decrease in appetite, and loss of interest in her usual activities. She was able to recall two out of three words, and accurately placed the numbers on a clock face but could not place the hands to indicate the correct time. Mrs. D was still continent and able to dress herself when clothing was placed on her bed. She appeared still to be in the mild stage of dementia.

The psychiatrist reviewed Mrs. D’s current medical status with her primary care physician and made several recommendations regarding her treatment. Ms. S was advised to try enrolling her grandmother in a local adult day program that provided dementia care, including activities, meals, and socialization. She would be able to continue her four hours of daily home attendant services after the program ended to provide more support until Ms. S came home from work. Ms. S was referred to a family and caregiver support group run by the day program. Mrs. D was started on mirtazapine 7.5 mg at bedtime for her depressive symptoms. The dose was gradually increased over the next 6 weeks to 30 mg at bedtime. Mrs. D started sleeping better at night. She attended the day program 4 days per week and gradually started to engage in activities and programs.

At a 3-month follow-up visit Mrs. D appeared brighter, with less distress. She continued on the mirtazapine 30 mg at bedtime. She was sleeping five or six hours at night and was eating more of her meals. Mrs. D started going on some trips with the day program. Her grooming appeared better, and she was able to talk about her family. Ms. S started attending some caregiver support meetings and reported that her grandmother was doing better. She was thinking of rearranging her work hours in order to spend more time at home, and overall felt more hopeful.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Lantz is Chief of Geriatric Psychiatry, Beth Israel Medical Center, First Ave @ 16th Street #6K40, New York, NY 10003; (212) 420-2457; fax: (212) 844-7659; e-mail: mlantz@chpnet.org.