Foreign Body Aspiration: 2 Cases

Children who present with acute or prolonged respiratory symptoms require a high index of suspicion for foreign body aspiration (FBA). We present 2 cases that highlight the importance of eliciting a choking history in any child presenting with respiratory symptoms. Early investigation with bronchoscopy is warranted when a strong clinical suspicion exists for FBA, since bronchoscopy helps to resolve symptoms quickly and prevent complications.

CASE 1: BOY WITH RESPIRATORY DISTRESS

A 2-year-old boy with a chief concern of sudden-onset difficulty breathing was transferred to our emergency department (ED) from another facility. At the other facility, the patient’s vital signs were as follows: temperature, 37.4°C; respiratory rate, 40 breaths per minute; pulse, 110 beats per minute; blood pressure, 92/60 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 80% on room air. He had no nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, stridor, or previous history of difficulty breathing.

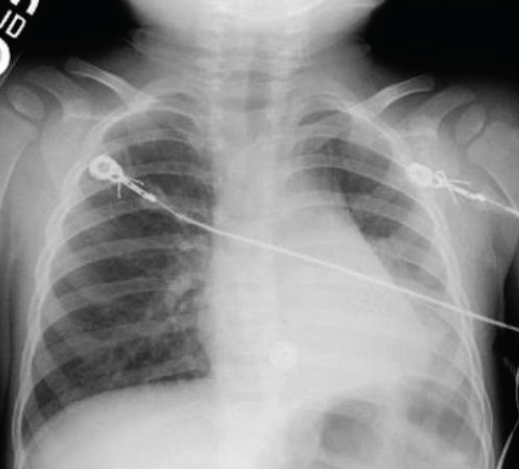

Physical examination findings at the other facility included tachypnea and suprasternal and subcostal retractions, with equal bilateral air entry and no adventitious breath sounds. At that time, he was placed on a nonrebreather mask and underwent chest radiography, the results of which showed a possible small left retrocardiac opacity (Figure 1). The patient then was transferred to our facility for further management.

Figure 1. Chest radiograph of a 3-year-old boy with difficulty breathing, taken at the referring facility, showing a possible small left retrocardiac opacity.

Upon arrival at our ED, his vital signs were as follows: temperature, 38.4°C; respiratory rate, 45 breaths per minute; pulse, 140 beats per minute; blood pressure, 90/64 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 100% on a nonrebreather mask. On physical examination, he was noted to have suprasternal and subcostal retractions, with decreased air entry to the left lower lung field.

Upon questioning, the patient’s father reported that the boy had choked on an almond chocolate and had been coughing for a brief period the day before presentation. Chest radiography was repeated in our ED 3 hours after the scan at the other facility; the results showed left retrocardiac and left lower lobe opacity (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Chest radiograph of the boy, taken at the authors’ facility 3 hours later, showing left retrocardiac and left lower lobe opacity. A piece of almond later was removed from the left main bronchus.

Otolaryngology was consulted, and the patient underwent emergent rigid bronchoscopy for possible FBA, during which a piece of almond was removed from the left main bronchus. His postoperative course was uncomplicated, and he was discharged home the following day.

CASE 2: BOY WITH PERSISTENT COUGH

A previously healthy 7-year-old boy was referred by his primary care provider to our ED with a chief concern of cough for 1 week and difficulty breathing while running and playing at school for the last 2 days. According to the primary care provider’s report, the boy had no nasal congestion, fever, drooling, dysphagia, wheezing, or stridor. His symptoms had not been alleviated by over-the-counter cough remedies nor inhaled β-agonists prescribed by his primary care provider.

In our ED, his vital signs were as follows: temperature, 36.8°C; respiratory rate, 20 breaths per minute; pulse, 90 beats per minute; blood pressure, 108/70 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 98% on room air. Physical examination revealed a comfortable child in no apparent distress, but with significantly decreased air entry in the left lung field with no adventitious breath sounds.

Upon questioning, the patient reported that he had been chewing on the plastic end of a mechanical pencil 1 week before presentation and had choked on a small piece, which he thought he had swallowed.

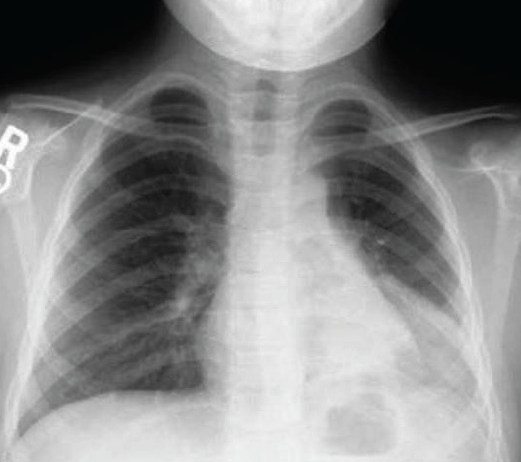

Figure 3. Posteroanterior chest radiograph of a 7-year-old boy with persistent cough showing an opacity in the left lower lobe and hyperinflation of the right lung.

Chest radiographs taken in our ED were remarkable for an opacity in the left lower lobe on posteroanterior view (Figure 3) and lateral view (Figure 4), with significant hyperinflation of the boy’s right lung. Left lateral decubitus view showed an incomplete collapse of the left lung (Figure 5).

Otolaryngology was consulted, and the patient underwent an elective rigid bronchoscopy for possible FBA. During the procedure, a small plastic object surrounded by granulation tissue and mucopurulent secretions was found at the left secondary bronchus and was removed. His postoperative course was uncomplicated, and he was discharged home after few hours of observation.

Figure 4. Lateral chest radiograph of the boy showing an opacity in the left lower lobe and hyperinflation of the right lung.

DISCUSSION

The majority of pediatric FBAs occur in children younger than 3 years of age.1 Boys are more commonly affected than girls.2 Predisposing factors for FBA in these patients include the smaller diameter of their airway, the tendency to introduce objects into the mouth, immature dentition, activity while eating, and having older siblings (who may place food or objects into the mouths of infants or toddlers).3,4 In older children, anatomic abnormalities and neurologic disorders predispose to FBA.5 Food (eg, peanuts, seeds, nuts, popcorn, hotdogs, beans, carrots, corn) is the most common item aspirated by infants and toddlers. Nonfood items (eg, coins, balloons, paper clips, pins, toy parts, needles, pen caps) more commonly are aspirated by older children.6 Most objects aspirated by children are radiolucent, whereas only 18% to 20% of aspirated foreign bodies are radiopaque.4,6 Plastic pieces account for 5% to 15% of FBAs and tend to remain in place longer because they are inert and radiolucent.3,6,7

Figure 5. Left lateral decubitus radiograph of the boy’s chest showing incomplete left lung collapse. The plastic end of a mechanical pencil later was removed from the left secondary bronchus.

The majority of aspirated foreign bodies in children are located in the bronchi.2,3 In a review of 1,160 cases of FBA in Turkey,2 the sites of the foreign body were as follows: larynx, 3%; trachea/carina, 13%; right lung, 59% (52% in the main bronchus, 6% in the lower lobe bronchus, and less than 1% in the middle lobe bronchus); left lung, 23% (18% in the main bronchus and 5% in the lower lobe bronchus); bilateral, 2%. In a review of 2,165 FBA cases in Egypt, the majority of the foreign bodies were located in the left main bronchus, with no statistically significant difference for the left and the right sides.7

PRESENTATION

A history of the clinical triad of choking, wheezing, and coughing is important to elicit, especially in context of other acute clinical signs and symptoms.1 Acute signs and symptoms depend on the location of the foreign body and include choking episodes, cough, neck pain, throat pain, stridor, dyspnea, hoarseness, cyanosis, and wheezing. Patients who present later may complain of hemoptysis and fever in addition to cough, dyspnea, and wheezing.2,3,8 Compared with bronchial foreign bodies, laryngotracheal foreign bodies tend to present more acutely. The classic triad of wheeze, cough, and diminished breath sounds is not present in all cases. In a review of 135 cases of airway foreign body in children, this triad was present in only 57%.3

A previous diagnosis of asthma or pneumonia as the explanation for recurring symptoms makes the history potentially misleading. Although a history of a choking event may be the most sensitive factor predicting FBA, the history often must be elicited.

In children presenting with complete airway obstruction (ie, sudden respiratory distress followed by the inability to speak or cough), dislodgement using back blows and chest compressions in infants, or the Heimlich maneuver in older children, should be attempted.“Blind” sweeping of the mouth should not be performed. When the obstructing foreign body is below the larynx and does not move with standard recommended procedures, intubation may permit some ventilation until rigid bronchoscopy is possible.

Patients experiencing partial airway obstruction should be placed in a position of comfort and emergently transferred to a facility capable of airway management and bronchoscopy without being delayed by imaging.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Asymptomatic and clinically stable patients presenting immediately after a choking event and with normal examination findings should undergo imaging studies. Inspiratory and expiratory or decubitus films of the chest may be helpful in establishing the diagnosis of FBA.4,9 The common radiographic finding in lower airway aspiration is air trapping. An early finding on radiographs is a hyperinflated lung contralateral to the obstructed airway. Atelectasis, consolidation, and a contralateral mediastinal shift are late findings on radiographs of the affected airway.4,5,8

Soft tissue films of the neck can be beneficial for detecting objects in the upper airway, but normal radiographs cannot exclude an airway foreign body.8 Airway fluoroscopy may be helpful in diagnosis of FBA if the results of plain radiography are normal or equivocal.10 Sensitivity and specificity of radiography can vary.4

Computed tomography of the chest may have some additional benefit in acute aspirations. It can help define radiolucent foreign bodies such as fish bones and provide useful information (such as the location and size of the object, parenchymal changes, and the degree of granulation) before attempted extraction.

If strong suspicion of FBA exists, bronchoscopy should be performed despite negative results on imaging studies. Rigid bronchoscopy is the procedure of choice and the standard of care for the evaluation of children with suspected FBA.8,11 Clinicians who are experienced with flexible bronchoscopy also have reported using it to extract the object.12 Thoracotomy is indicated in rare cases in which foreign bodies are visualized but cannot be removed with rigid bronchoscopy.13

COMPLICATIONS AND FOLLOW-UP

The most serious complication of FBA is complete obstruction of the airway.3 The longer the foreign body is retained, the more likely are complications (eg, atelectasis, persistent or recurrent pneumonia or abscess, pneumothorax, stricture, perforation, airway granulomas, bronchopulmonary fistula, bronchiectasis).4,5,6,8

No published studies have evaluated the need for postoperative antibiotics or corticosteroids, although most authors recommend their use, especially if there is granulation tissue or any concern for infection.8

REFERENCES:

1. Sahin A, Meteroglu F, Eren S, Celik Y. Inhalation of foreign bodies in children: experience of 22 years. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(2):658-663.

2. Eren Ş, Balci AE, Dikici B, Doblan M, Eren MN. Foreign body aspiration in children: experience of 1160 cases. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2003;23(1):31-37.

3. Tan HKK, Brown K, McGill T, Kenna MA, Lund DP, Healy GB. Airway foreign bodies (FB): a 10-year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;56(2):91-99.

4. Digoy GP. Diagnosis and management of upper aerodigestive tract foreign bodies. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41(3):485-496.

5. Holinger LD, Poznanovic SA. Foreign bodies of the airway and esophagus. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. Vol 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:2935-2943.

6.Karakoç F, Karadağ B, Akbenlioğlu C, et al. Foreign body aspiration: what is the outcome? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;34(1):30-36.

7. Sersar SI, Rizk WH, Bilal M, et al. Inhaled foreign bodies: presentation, management and value of history and plain chest radiography in delayed presentation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(1):92-99.

8. Srivastava G. Airway foreign bodies in children. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2010;11(2):67-72.

9. Assefa D, Amin N, Stringel G, Dozor AJ. Use of decubitus radiographs in the diagnosis of foreign body aspiration in young children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23(3):154-157.

10. Rudman DT, Elmaraghy CA, Shiels WE, Wiet GJ. The role of airway fluoroscopy in the evaluation of stridor in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(3):305-309.

11. Hui H, Na L, Zhijun C, et al. Therapeutic experience from 1428 patients with pediatric tracheobronchial foreign body [published correction appears in J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(3):662]. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(4):718-721.

12. Ramírez-Figueroa JL, Gochicoa-Rangel LG, Ramírez-San Juan DH, Vargas MH. Foreign body removal by flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy in infants and children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40(5):392-397.

13. Soysal O, Kuzucu A, Ulutas H. Tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration: a continuing challenge. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(2):223-226.

Dr Patel is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow and Dr Shihabuddin is an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Medicine, at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City.