Head Lice: A Most Unwelcome Invasion

CASE: A 12-year-old healthy girl has had an itchy scalp and rash on the neck associated with swollen lymph nodes for the past few weeks. Her mother reports that several of her daughter’s friends at school have experienced similar symptoms.

Close examination reveals excoriated red macules and papules on the child’s neck and eggs, nits, and lice in the hair, confirming a diagnosis of head lice infestation. The mother has heard that head lice can be difficult to treat.

How will you advise her?

(Discussion on next page.)

Head Lice Infestation: Treatment Recommendations

The recent increase in FDA-approved medications for the treatment of head lice infestation has given providers numerous therapeutic options. The multitude of choices, however, may lead to confusion and indecision regarding treatment recommendations. Knowledge of the biology/life cycle of the head louse and each drug’s mechanism of action, potential adverse effects, and prescribing information is crucial in creating an appropriate treatment plan.

First-line treatment options include topical therapy with pyrethrin, permethrin, dimeticone, malathion, benzyl alcohol, spinosad, and ivermectin. Only malathion, spinosad, and ivermectin are believed to have significant ovicidal activity, possibly eliminating the need for a second treatment. In our opinion, all therapies should be administered twice separated by 7 to 10 days. In addition to the general measures aimed at prevention of reinfestation, we recommend adjunctive wet combing to all patients.

OTC synergized pyrethrins, 1% permethrin, and/or 4% dimeticone should be used first because these therapies have proven safety and low cost. Dimeticone, in particular, may be underutilized in the United States. With persistent infestation, malathion, benzyl alcohol, spinosad, and topical ivermectin are all reasonable, albeit expensive, treatment options.

Although not FDA-approved for the treatment of head lice infestation, oral ivermectin is an efficacious, economical, and safe adjunctive or alternative therapy.

Lack of compliance, misdiagnosis, and/or reinfestation should always be considered in addition to treatment resistance when infestation persists.

Infestation of scalp hair by Pediculus humanus capitis occurs worldwide, most commonly in children aged 3 to 12 years. Head lice are blood-feeding, wingless, host-specific ectoparasites of about 2-mm long with 3 pairs of legs.

The entire life cycle of the louse occurs on the human scalp. The female louse lays 5 to 10 eggs per day about 1 cm away from the scalp. The eggs hatch in 10 days, and the empty eggshells (nits) remain firmly attached to the hair shaft. Immature lice (nymphs or instars) complete 3 stages of development to become mature adult lice.

Away from the scalp, adult lice cannot survive more than 2 to 4 days but viable eggs can survive for up to 10 days. Head-to-head contact or contact with fomites infested with viable eggs, nymphs, or adult lice is the mode of transmission. The incubation period is 4 to 6 weeks.

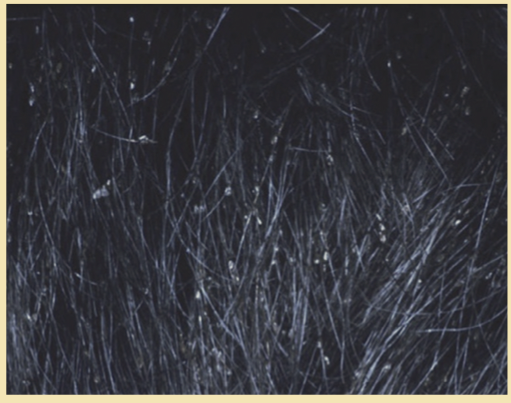

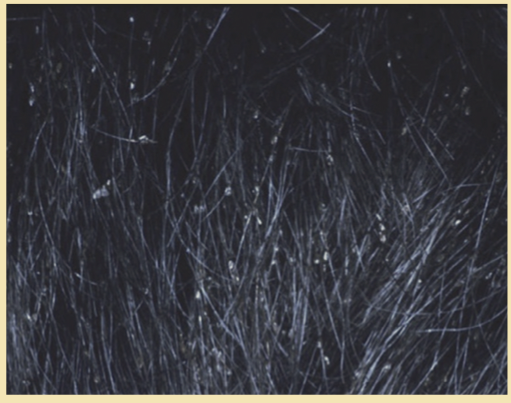

Patients commonly present with an itchy scalp. Nonspecific features include excoriated red macules and papules—present in this patient (Photo A). Examination of affected hair most often reveals eggs and nits attached to the hair shaft (Photo B). However, the diagnosis of an active head lice infestation requires identification of a living louse, shown here. The presence of eggs usually, but not always, indicates active infestation as well. Live lice avoid light and blend in with hair. They can be more readily detected by “wet combing” lubricated hair with a fine-tooth comb.

The differential diagnosis of pediculosis capitis includes seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, tinea capitis, psoriasis, insect bites, use of cosmetic hairstyling products, piedra, delusions of parasitosis, and pseudonits (desquamated epithelial cells loosely attached to hair shafts).

Treatment of head lice infestation can broadly be divided into neurotoxic and non-neurotoxic therapy (Table).

Treatment of head lice infestation can broadly be divided into neurotoxic and non-neurotoxic therapy (Table).

Neurotoxic pediculicides. Concerns about the potential adverse effects and increasing drug resistance associated with topical and oral neurotoxic pediculicides have limited the use of some of these medications. These treatments are generally administered in 2 doses separated by 7 to 10 days in order to allow surviving eggs to hatch, with the resulting nymphs killed by the second application.

Over-the-counter (OTC) topical synergized pyrethins and 1% permethrin are applied to the scalp for 10 minutes before being rinsed out. These products work by disrupting sodium transmission across lice cell membranes. Prescription 5% permethrin cream is applied overnight to a dry scalp and washed out the following morning. The efficacy of pyrethins and permethrin today is affected by significant resistance patterns that vary geographically.

The neurotoxic treatments demonstrated to be most efficacious in clinical trials include oral ivermectin tablets and topical malathion 0.5% lotion. Oral ivermectin is dosed 200 ug/kg and should not be given to pregnant women or children who are younger than 5 years or who weigh less than 15 kg. Ivermectin binds to and activates insect glutamate-gated chloride channels. In February 2012, the FDA approved ivermectin 0.5% lotion for the topical treatment of head lice in patients 6 months and older. The pivotal studies demonstrated that 75% of patients treated with a single 10-minute application of ivermectin 0.5% lotion without nit-comb use were free of live lice at day 14.1

Malathion 0.5% lotion, an organophosphate that irreversibly binds cholinesterase, is applied overnight before being rinsed out. It is approved for the treatment of head lice in patients 6 years and older. Patients should be warned that it can lead to burning/stinging sensations on the scalp and is highly flammable. Of note, recent epidemiologic studies have linked organophosphate exposures (including malathion) in children with increased prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.2 Causality is uncertain and the clinical relevance with single topical applications of malathion used for head lice is unclear.

A naturally occurring neurotoxin spinosad, obtained from fermentation of Saccharopolyspora spinosa, has been found to interfere with functioning nicotinic and g-aminobutyric acid ion channels and lead to neuronal excitation, paralysis, and death of lice.3 Spinosad 0.9% suspension obtained FDA approval in 2011 for the treatment of head lice in children 4 years and older as a 10-minute topical application without nit combing. Clinical trials have demonstrated cure rates of 85% at 14 days and greater effectiveness than topical 1% permethrin.4

Lindane may be considered after other treatment options have been exhausted, although extreme caution is necessary when prescribing this medication. This neurotoxic therapy is available as a 1% shampoo that must be rinsed out after 4 minutes. An FDA black box warning states that lindane may be associated with severe neurologic toxicity. Its use is contraindicated in premature infants and patients with uncontrolled seizure disorders.

Pesticide-free options. Use of non-neurotoxic therapy is increasingly being sought to avoid potential adverse effects associated with chemical neurotoxins and resistance to insecticides.

Simple physical measures include combing out nits from wet hair with use of specialized nit combs or shaving the scalp hair. The latter, although effective, may be undesirable for cosmetic reasons. Wet combing is a useful adjuvant therapy; however, there is limited evidence to suggest that it is an effective monotherapy, and cure rates published in the literature are quite variable.5 Patients (and their parents) are advised to thoroughly comb the entire scalp until all visible nits are removed every 3 days for 14 days.6 Use of topical OTC formulations containing 5% acetic acid, 8% formic acid, and acid shampoos or conditioners (pH 4.5 to 5.5) may help loosen nits from hair shafts.7

Commercial services that offer specialized wet combing treatments have recently expanded in developed countries. Because of the expense and lack of data on the efficacy of these services, it is difficult to routinely recommend them. A recent addition to the commercial armamentarium is a medical device that uses hot air to inflict thermal damage to eggs and lice.8

Additional physical therapies under investigation include the topical application of a variety of occlusive and suffocation products (eg, petrolatum, mayonnaise, vegetable oil, mineral oil, hair pomade, olive oil, and Cetaphil® cleansing lotion). These products are generally messy in practice and have uncertain and variable efficacy.

In randomized controlled trials, dimeticone, a silicone-based oil with a low surface tension and special spreading properties, has been shown to have cure rates between 70% and 97% after 2 applications separated by 7 days.9 Dimeticone pediculicides have an excellent safety profile, are OTC agents, and are widely used as first-line treatment in the United Kingdom.

Benzyl alcohol lotion, 5%, is believed to asphyxiate the louse by stunning its breathing mechanism. Two clinical trials comprising more than 600 participants demonstrated cure rates in excess of 75%.10 This non-neurotoxic prescription medication received FDA approval in 2009 for use in patients older than 6 months.

Plant-based pediculicides containing various essential oils may represent a future treatment option.11 Among the more promising candidates are eucalyptus, lavender, and tea tree oil.

General measures. Whatever strategy is chosen to treat a head lice infestation, prevention of reinfestation should be emphasized. This includes washing recently used clothing, bedding, and towels in hot water; treating combs and brushes with hot water or pediculicides; and vacuuming carpets, upholstery, and furniture to remove hairs with viable eggs.

All family members should be examined for evidence of infestation and treated accordingly. Those who share bedding should receive empiric treatment. It is important to emphasize that all family members who receive treatment should do so simultaneously to minimize reinfestation.

Children with an active head lice infestation can return to school after the first pediculicidal treatment. The presence of nits alone should not exclude children from returning to school.