Infant With Emesis and Stomach Full of Formula

Case in Point

An Intriguing Diagnosis

A 6-week-old term infant with a previous diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was hospitalized because of worsening vomiting. Her mother reported that the infant had had emesis numerous times per day starting at 2 to 3 weeks of age. The girl was treated with ranitidine, and her formula was changed from regular to a sensitive formula, but no significant improvement in symptoms resulted.

A few days before admission, the frequency of vomiting had increased dramatically to up to 20 times per day. The emesis remained nonbloody and nonbilious, and it looked like partially digested formula. The mother also reported that the infant had decreased oral intake, decreased urine output, and decreased stools. The baby had been afebrile and was tracking at the 50th percentile for weight.

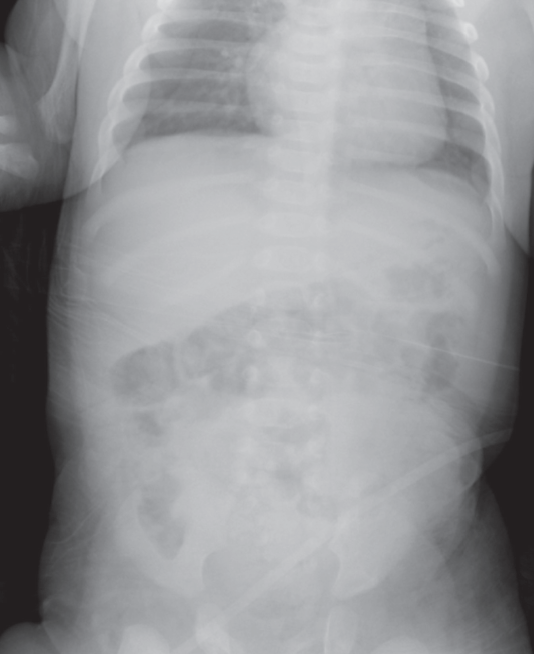

Figure 1 – Chest radiograph of a 6-week-old girl with emesis showed a mottled mass-like filling defect in the stomach.

On admission, the infant was well nourished, well hydrated, and active. Her abdomen was soft, nondistended, and nontender, with normal active bowel sounds and no appreciable masses. Results of the rest of the examination were normal.

Imaging was ordered. For unclear reasons, a radiograph of the chest rather than of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder (KUB) was obtained. The chest radiograph showed a mottled mass-like filling defect in the stomach forming a cast of the stomach (Figure 1), which was concerning for a gastric lactobezoar.

On further questioning, the mother reported mixing the infant formula with the correct ratio of formula to water and shaking the bottle to dissolve any clumps. The infant was fed 4 oz every 4 hours.

The girl was admitted to the hospital, given nothing by mouth, and given intravenous fluids overnight. The next morning, a KUB radiograph showed complete resolution of the mass (Figure 2). The infant tolerated oral rehydration solution and formula and was discharged home with instructions for her mother to continue ranitidine and supportive care for GERD.

Figure 2 – Radiograph of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder showed complete resolution of the lactobezoar.

LACTOBEZOAR: AN OVERVIEW

Use of the word bezoar dates to the 16th century and can be traced to the Persian word pad-zahr. In Farsi, pad translates to “against,” zahr translates to “poison,” and combined they refer to an antidote or cure. Bezoars once were thought to be valuable and to possess magical healing properties. Today bezoar has a different denotation: It is a mass of foreign material present in the gastrointestinal tract. There are several types of bezoars, including trichobezoars (comprising hair), phytobezoars (indigestible plant material), pharmacobezoars (medications), and lactobezoars (inspissated milk).1

Clinical presentation. Lactobezoars are foreign bodies produced in the gastrointestinal tract by the accumulation of undigested milk concretions. They most often are found in infants. Some common presenting symptoms include nonbilious emesis, dehydration, abdominal distension, and gastric residuals.2

The formation of a lactobezoar can result in a cycle in which persistent vomiting from the initial formation leads to dehydration and reduced gastric secretions, causing further accumulation of milk concretions. The lactobezoar then causes obstruction, perpetuating the vomiting and dehydration. Serious complications can include metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities caused by persistent vomiting, gastric outlet obstruction, and rarely, gastric perforation.3

Possible causes. Three theories have been proposed about the etiology of lactobezoars. Lactobezoars initially were thought to occur most often in preterm, low-birth-weight infants being fed calorie-dense formula, as Levkoff and colleagues4 delineated in their 1970 report of a lactobezoar in an infant fed 24-kcal/oz formula. In the late 1970s, lactobezoars were thought to be secondary to dehydration or to formulas that were overconcentrated due to improper preparation, as Wexler and Poole5 reported in their case report of a 7-day-old term boy who had been receiving undiluted formula. In the early 1980s, Schreiner and colleagues6 suggested that infants given formula with a high casein-to-whey protein ratio were at increased risk for the development of lactobezoars.

However, these etiologic theories have been unable to explain all cases of lactobezoar. Our patient was a full-term healthy infant being fed with an appropriately mixed 20-kcal/oz formula. In 1989, Usmani and Levenbrown7 described a lactobezoar in a full-term, breastfed infant. Bakken and Abramo3 reported a case of gastric outlet obstruction from a lactobezoar in a 5-day-old infant being fed a soy protein–based formula. DuBose and colleagues,2 in their case report of a 3-year-old boy who was found to have a lactobezoar after presenting with protracted vomiting, showed that lactobezoars can occur in patients other than infants.

Given the lack of an obvious unifying etiology, several factors most likely contribute to the formation of gastric lactobezoars.

Treatment. Conservative treatment, withholding feedings and giving intravenous fluids for 24 to 48 hours, is the primary approach, as was done with our patient. Imaging tests often are repeated to establish that the mass has dissolved. If conservative therapy is unsuccessful, surgery may become necessary.2

REFERENCES:

1. DeBakey M, Ochsner A. Bezoars and concretions: a comprehensive review of the literature with an analysis of 303 collected cases and a presentation of 8 additional cases. Surgery. 1938;4:936-963.

2. DuBose TM V, Southgate WM, Hill JG. Lactobezoars: a patient series and literature review.

Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2001;40(11):603-606.

3. Bakken DA, Abramo TJ. Gastric lactobezoar: a rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13(4):264-267.

4. Levkoff AH, Gadsden RH, Hennigar GR, Webb CM. Lactobezoar and gastric perforation in a neonate. J Pediatr. 1970;77(5):875-877.

5. Wexler HA, Poole CA. Lactobezoar: a complication of overconcentrated milk formula. J Pediatr Surg. 1976;11(2):261-262.

6. Schreiner RL, Brady MS, Ernst JA, Lemons JA. Lack of lactobezoars in infants given predominantly whey protein formulas. Am J Dis Child. 1982;136(5):437-439.

7. Usmani SS, Levenbrown J. Lactobezoar in a full-term breast-fed infant. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84(6):647-649.