Left Acute Viral Parotitis

A 10-year-old boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with 2 days of left-sided face and neck pain, swelling, and low-grade fever. He had been seen the day before at an otolaryngology clinic for the symptoms and had been placed on cephalexin, sialagogues, and massage of the left parotid area. Despite treatment, his symptoms continued to worsen, with increased pain and swelling, and he was referred to the ED for concerns of parotitis.

His past history was significant for surgical repair of cleft lip and palate, ear surgeries with tympanostomy tube placements, left mastoidectomy, and chronic ear drainage.

Upon examination in the ED, the boy had a temperature of 36.7°C, a pulse of 112 beats/min, and a respiratory rate of 28 breaths/min. Pertinent clinical findings included a 6 × 5-cm area of diffuse, nonerythematous, tender, soft, nonfluctuant, edematous, swelling of the left side of the face, extending from the angle of mouth to the preauricular area, and from the angle of the left jaw down to the upper part of neck, with tenderness over the posterior aspect of the swelling (A).

The left parotid duct was slightly edematous, with no palpable mass or stone in the duct, according to the otolaryngologist’s report from the previous day. Numerous small anterior cervical nodes were palpable, more on the left side than on the right. Scarred, thickened tympanic membranes were visualized bilaterally. The rest of the examination findings were normal.

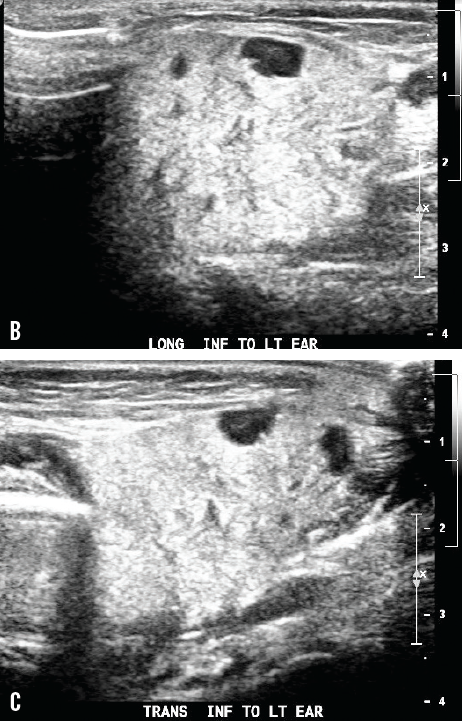

The total white blood cell count was 16,000/µL with 76% neutrophil predominance, the C-reactive protein level was 1.75 mg/dL, and the amylase level was 590 U/L; blood was sent for bacterial culture. Ultrasonography examination of the area showed an echogenic, asymmetrically enlarged, edematous left parotid gland, with round hypoechoic foci within, representing intraparotid lymph nodes (B and C) and left cervical chain nodes, without evidence of abscess formation.

Based on clinical findings, laboratory reports, and ultrasonography reports, the patient received a diagnosis of left acute parotitis. The patient was treated with intravenous clindamycin 300 mg and intravenous dexamethasone 8 mg and was admitted to the hospital for observation. Bacterial culture was reported negative, and a final diagnosis of viral parotitis was made. The boy was sent home with a 10-day regimen of oral clindamycin.

Discussion

The etiology of parotid swelling can be infectious or noninfectious. The sudden onset of an indurated, warm, erythematous swelling of the cheek extending to angle of jaw is characteristic of acute parotid infection. Epidemic mumps caused by paramyxovirus is the most common cause of viral parotitis among children. Painful parotitis occurs in 60% to 75% of infections and in 95% of patients with symptoms.1

Typically, parotid gland swelling starts with a short prodromal phase of low-grade fever, anorexia, malaise, and headache; it then progresses over 2 to 3 days and persists for about a week. The degree of pain and tenderness of the swelling is related to the progression and resolution of parotitis.

Aside from paramyxovirus, other viral causes of sporadic swelling include coxsackievirus A, Epstein-Barr, influenza A, and parainfluenza. The differential diagnosis for parotid enlargement includes juvenile recurrent parotitis, cystic adenitis, dental abscess, Ludwig angina, infected cysts, sialolithiasis, cystic fibrosis, sarcoidosis, collagen vascular disorders, and lymphoma. Predisposing factors include a septic focus in the oral cavity, dehydration, malnutrition, immunosuppression, and the use of antihistamines and diuretics.2

The diagnosis of parotitis is primarily clinical. Sonography of the gland may help confirm the diagnosis and rule out abscess formation. Elevations of white blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein level and serum amylase level are observed in patients with suppurative parotitis. Serum amylase is elevated in 90% of patients, differentiates parotitis from adenitis, and is not a specific indicator of viral parotitis.2 Raising serum antibody titers usually identify viral causes once the acute episode subsides.

Maintenance of good oral hygiene and adequate hydration and the administration of broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics to cover aerobic and anaerobic pathogens may reduce the occurrence of suppurative parotitis.

References:

1.Koch BL, Myer CM III. Presentation and diagnosis of unilateral maxillary swelling in children. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20(2):106-129.

2.Brook I. Diagnosis and management of parotitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118(5):469-471.