Management of Colorectal Cancer in the Elderly

This article is the second in a continuing series on cancer in older adults. The first article of the series, “Challenges in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer in the Elderly,” was published in the November 2009 issue of the Journal. The goal of this series of articles is to highlight the ways in which cancer diagnosis and management in older adults differ from cancer diagnosis and management at younger ages. Other topics that will be included in the series are cancer and aging, prostate cancer, hematologic malignancies, cancer screening and prevention, and palliative care and hospice.

Introduction

Older patients with colorectal cancer are underrepresented within oncology clinical trials.1,2 Although colorectal cancer primarily affects the elderly, pivotal trials establishing evidence-based care for this disease have tended to include patients with a median age of 60-65 years, with fewer than 20% of persons age 70 years and over. The net effect of lack of clinical trial data is a delayed understanding of the optimal management of colorectal cancer among the elderly as compared to younger patients, despite the fact that the mean age of persons with colorectal cancer is 72 years at diagnosis.3 There is even a more significant dearth of information regarding treatment efficacy and safety for colorectal cancer in the “oldest-old” subgroups and for those who are more vulnerable due to underlying comorbidity or functional limitations. In this article, we provide an approach to the assessment of the older patient for colon cancer screening and treatment, and an overview of management options for colon cancer treatment along the full clinical continuum of the disease. Our goal is to both elucidate existing evidence and to identify knowledge gaps regarding the care of older persons with colorectal cancer.

Epidemiology

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer among both sexes, and it accounted for 49,960 deaths in 2008 alone.4 Patients older than 65 years of age currently comprise 67% of the disease burden.5 Approximately half of all men diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 60% of women in the United States are older than 70 years at diagnosis. The incidence increases with advancing age, doubling every seven years for patients age 50 years and over.6

Although colon and rectal cancer are often grouped together, there are important management distinctions to make, both medically and surgically. The surgical options in rectal cancer are more varied than with colon cancer, and additional quality-of-life issues such as anal sphincter preservation and bladder function must be weighed along with bowel alterations. Pathologic staging is not usually available at the time treatment is initiated in rectal cancer, a disease in which neoadjuvant chemoradiation has become the standard of care in suitable patients. Imaging modalities must rely primarily on size criteria to distinguish pathologic from non-pathologic lymphadenopathy, resulting in decreased sensitivity and specificity as compared to pathologic staging. Since decision making in rectal cancer is already more complex, its reliance on less accurate staging criteria further complicates decision making for the clinician. The potential for undertreatment due to the inherently less sensitive clinical staging required in rectal cancer would be comparable among younger and older patients. However, the potential for causing harm as a result of overtreatment is especially important to consider among the elderly, in whom quality-of-life issues are balanced with a narrow therapeutic index of treatment. Although the distinction between colon and rectal cancer is a subject unto itself, we wanted to highlight some of the fundamental differences facing clinicians today.

For both colon and rectal cancer, patients within the older age demographic are more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage, which may contribute to a decreased survival among this population.7 The Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group’s systematic review of outcomes from colorectal cancer surgery found a linear relationship between age and stage at diagnosis.8 In this meta-analysis, while 73% of those age 65 and under survived 2 years, rates declined to 66% in those age 65-74 years, 57% in those 75-84 years, and 39% in those age 85 years and over. Another study by Jessup et al9 that analyzed adjuvant chemotherapy use among 85,934 patients with stage III colorectal cancer between 1990-2002 showed a trend toward more advanced stage in those older than age 80. However, other studies and data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry suggest that age may not have a strong influence on stage at diagnosis.10 Differences in the upper age limit among studies that stratify patients contribute to the discrepant findings of the age-stage relationship. For example, SEER data do not further stratify beyond those older than 75 years, while age stratification in the other studies extends into the ninth decade.

In contrast to the inconsistent relationship between age and stage of diagnosis, data regarding the influence of age on receipt of treatment are more uniform. There is compelling evidence from systematic reviews that age influences the receipt of both surgical and chemotherapy options.8,9,11-13 Furthermore, these and additional studies have shown that the influence of age on receipt of treatment is independent of stage at diagnosis.13 Independent of stage, older persons are less likely to undergo curative resection and receive adjuvant chemotherapy as compared to their younger counterparts.8,9

Despite underrepresentation within clinical trials and a comparatively lower receipt of treatments, we are making improvements in the care of older patients with colon cancer. Colorectal cancer death rates decreased by approximately 6% from 2003-2004 as compared with a 3% decrease from 2004-2005.4 A recent model analyzing long-term cancer survival in the United States also showed an increase in the 5-year relative survival rate among colon cancer patients age 65 years and older from 1998-2003 (61.9% vs 65.8%; P for trend < 0.001); this increase was greater than that demonstrated by patients under age 65 years in the same period (64.6% vs 67%; P for trend < 0.06) and was attributed to improved screening and treatment modalities.14 Another study of 838 rectal patients age 80 and over showed an improvement in 5-year survival from 18% in 1978-1981 to 42% from 1994-1997.15

Biology of Colorectal Cancer in Older Persons

Although there are a number of well-defined genetic syndromes that increase the risk for developing colorectal cancer, the majority of colorectal carcinomas occur in those without an identifiable risk factor. Advanced age is the most significant risk factor for the development of colorectal cancer. The molecular changes that promote the adenoma to carcinoma sequence have been recognized for over two decades. These include somatic mutations in tumor suppressor genes, such as inactivation of the APC and DCC genes. Additional genetic defects in the pathway involve mutations in oncogenes such as K-RAS, along with allelic loss of tumor suppressor genes such as p53 and 18q. The Figure is a schematic representation of molecular changes from progression of adenoma to carcinoma. Although the adenoma-carcinoma sequence does not vary with age, longevity promotes accumulated mutations that contribute to developing sporadic colorectal carcinoma. This increase in somatic mutations with age is the premise for colorectal screening guidelines, despite the fact that most adenomas never progress to a carcinoma.

Epigenetic changes to DNA such as methylation provide an alternative pathway for colorectal cancer development.16 Methylation of DNA promoter regions silences transcription of that particular gene. Specifically, methylation of the mismatch repair gene hMLH1 causes decreased expression of the corresponding protein and resultant dysfunction of the mismatch repair mechanism. Accumulation of uncorrected transcription defects in areas of DNA microsatellites leads to colorectal oncogenesis and microsatellite unstable tumors.17 High microsatellite instability (MSI-H) is seen in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome, but the majority of MSI-H colorectal cancers (85%) arise via methylation of hMLH1.18

Because methylation is part of the natural aging process in colorectal mucosa, this phenomenon is particularly relevant for elderly patients with colon cancer, as they are more likely to be MSI-H than younger counterparts. The clinical significance lies in the fact that MSI-H colorectal cancers generally have a better prognosis than microsatellite-stable tumors. Furthermore, MSI-H cancers do not respond as well—and may actually do worse—when treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–based chemotherapy treatments.19

Screening

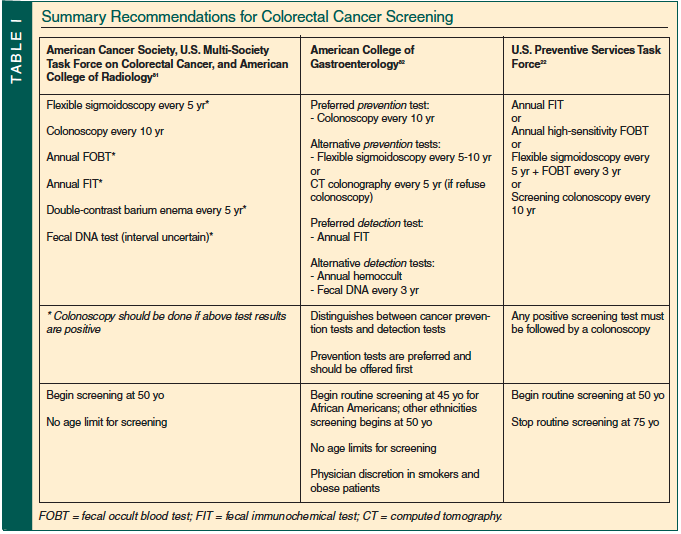

Improvement in screening techniques has made a significant impact on the early detection of colorectal cancer and has reduced morbidity and mortality from this disease. Most guidelines advocate screening for colorectal cancer in adults over age 50 with average risk.20,21 The most recent U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations emphasize the importance of screening with any method proven to reduce colorectal cancer–specific mortality.22 These screening options include annual high-sensitivity fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years coupled with highly sensitive FOBT every 3 years, or screening colonoscopy every 10 years with follow-up frequency dependent on results. Until 2008, the USPSTF recommended that routine screening for persons of average risk begin at 50 years of age, and no age limit was set at which to stop screening. A summary of recommendations for screening of average-risk patients by group is provided in Table I. Data for cancer screening in the oldest subgroups of the population are lacking because few cancer screening clinical trials have included patients age 70 and over.23 Therefore, clinicians are forced to extrapolate potential benefits of screening for the elderly population.24 In a recent revision to the 2002 guidelines, USPSTF no longer recommends routine colorectal cancer screening in those 75-85 years old, and recommends against any form of screening in patients older than 85 years.22 These limits are only guidelines, and other consensus groups recommend more individualized decisions, of which expected longevity, or remaining life expectancy, and screening history are important additional variables.25 A criticism of the USPSTF guidelines is that these guidelines continue to center on chronologic rather than physiologic age. For example, a healthy 75-year-old person may have greater than 10 years of life expectancy, and therefore may benefit from colorectal screening. Use of the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) may better help individualize screening decisions for those older than 75 years.

Despite recommendations for over a decade in support of screening, inadequate screening remains a national health issue. However, while the USPSTF task force analysis has identified racial and geographic disparities in colorectal screening in the United States, no evidence of an age disparity exists.22 In fact, the number of screening colonoscopies for colorectal cancer in elderly persons is increasing. An analysis of a population-based database, the National Health Interview Survey, showed that in the United States, the proportion of persons reporting up-to-date colorectal cancer testing increased from 39.5% in 2000 to 47.1% in 2005.26

Screening colonoscopy in very elderly persons (ie, age ≥ 80 yr) should be performed only after careful consideration of potential benefits, risks, tolerance of eventual antineoplastic treatments, and patient preferences.27,28 In one study that compared the impact of screening colonoscopy on outcomes of over 1200 elderly persons,28 the prevalence of cancerous lesions was 13.8% in the 50-54–year-old group, 26.5% in the 75-79–year-old group, and 28.6% in the group age 80 years or older. Despite higher prevalence of neoplasia in elderly patients, mean extension in life expectancy was much lower in the group age 80 years or older than in the 50-54–year-old group (0.13 vs 0.85 yr).

Even though prevalence of cancer increases with age, screening colonoscopy in very elderly persons (age ≥ 80 yr) results in only 15% of the expected gain in life expectancy in younger patients. Even though it is a relatively safe procedure, a higher risk of complications is seen in elderly patients. These risks include dehydration due to bowel preparation, electrolyte disturbances, and hypoxic complications or delirium from conscious sedation.27 Risk of perforation of colon was less than 0.5% in those age 75 and above, but was still four times higher than the 65-69–year age group, and the risk increased with higher numbers of comorbid conditions.29 Failure to reach the cecum is also more common in older patients due to inadequate bowel prep and likelihood of strictures. Newer screening techniques such as computed tomography colonography still require a bowel preparation, but do not have risks of perforation or bleeding. However, if a lesion is found, colonoscopy is still required for tissue diagnosis or intervention. The potential improvement in life expectancy derived from a particular cancer screening test should be weighed against the current physiologic status of the patient, the potential harms of screening, and the individual’s values and preferences.

Decision Making for Treatment in Older Patients with Cancer

The aging process is associated with a number of physiologic changes that may influence underlying health status and tolerance to cancer treatment. There is a gradual loss of physiologic reserve and decline in normal organ function with aging, such as decreases in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), gastrointestinal motility, cardiac reserve, and immune and hematologic function (Table II). These changes are associated with increased toxicity and decreased tolerance to chemotherapy drugs. Along with the physical changes, there are often social support or financial concerns and more of an unwillingness to accept significant adverse effects despite the relative effectiveness of the treatments in older populations.30 Therapeutic decision making should be individualized to the elderly patient. It is very important to select older individuals who would benefit the most from adjuvant chemotherapy and the ones who are at highest risk of significant side effects. Elderly patients who are considered “fit” are readily identifiable and should be offered the same treatment strategies as those used in younger patients. On the opposite end of the spectrum, physicians can easily identify patients who are frail and in whom less intensive, reduced dose, or no chemotherapy is preferred. The gray area resides in the intermediate or “vulnerable” category, which is much harder to define and even to recognize, as these elderly persons may have physical and/or functional deficiencies. For patients of intermediate status, issues of life expectancy and treatment tolerance become particularly relevant.31

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, CGA should be a key part of the treatment approach for vulnerable and frail older patients with cancer.32-34 The CGA is a means of assessing physiologic age and provides an assessment of functional reserve independent of chronologic age. Its use is advocated by geriatric oncologists to uncover predictors of functional decline, frailty, and mortality, which vary among patients of comparable age.33 This individualized assessment establishes the prevalence of functional impairment and comorbidities; these are important to assess, as dependence and disability are critical predictors of mortality among the elderly.35,36 In oncology, CGA could potentially help guide decision making, detect changes in geriatric outcomes over time, and identify target areas that would benefit from multidisciplinary geriatric interventions. A National Cancer Institute–sponsored trial has recently been established to assess the utility of the CGA in newly diagnosed colorectal cancer.

Surgery for Older Patients with Colorectal Cancer

Surgical resection of the primary tumor in the absence of metastatic disease is the main curative treatment approach for colorectal cancer. Nearly 90% of patients with stage I and early stage II colon cancers are cured with surgery alone. Curative options also exist for selected patients with advanced disease, including resection of liver or pulmonary metastasis, although there are limited data evaluating outcomes in elderly patients. Over the last decade, the numbers of surgeries for colorectal cancer in the elderly have increased, mainly due to improvements in surgical and anesthesia techniques.37 Improvement in survival from colorectal cancer has been attributed to the decrease in operative mortality and possibly the inclusion of surgery in the treatment plan for local or distant metastatic disease.7 Studies have shown that over 60% of patients requiring surgical intervention are age 70 and over.38

Elderly patients are also often viewed as high-risk surgical candidates, with high rates of emergency presentations and perioperative mortality. One registry study evaluated outcomes of 6457 patients with colorectal cancer from the Rotterdam Cancer Registry and found a disparity in treatment patterns between elderly and younger patients.39 Operative risk was greater than 10% for patients age 80 and over as compared to only 1% for those under the age of 60. Age was an independent prognostic factor for postoperative mortality in multivariate analysis. The Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group published a systematic review of data from 28 independent studies that included 34,194 patients.8 Older patients with an increased number of comorbid conditions were more likely to undergo emergency surgery and present with later-stage disease than younger patients. The investigators concluded that other factors associated with age, such as comorbidities, may confound the relationship between age and surgical outcomes, and that age alone should not preclude a curative surgical approach in elderly patients who are otherwise good risk. Laparoscopic colectomy is being increasingly employed for all colon cancer cases, but the benefits may be more pronounced in the elderly.40 The laparoscopic approach has been shown to be safe41 and associated with a shorter hospital stay in elderly patients.42,43

Outcomes of elderly persons who undergo palliative surgery in the metastatic setting have not been as well studied. Although palliative surgery is recommended for patients with bowel obstruction or bleeding, the benefits of surgery for removal of the primary tumor in asymptomatic stage IV colorectal cancer patients are uncertain, and this approach has been debated. Patients with colorectal cancer age 70 and over may benefit from liver resection for metastases, and can achieve significant progression-free and 5-year survival from this aggressive approach.44,45 However, mortality from the procedure is also higher in elderly patients as compared to their younger counterparts.46 A population-based analysis utilizing the Medicare-SEER database reported that 72% of elderly patients (n=9011) with stage IV cancer underwent primary-cancer-directed surgery within 4 months of diagnosis.47 Postoperative mortality at 30 days was 10%. Patients with left-sided colonic lesions or rectal tumors and those older than age 75 years, black, or of lower socioeconomic status were less likely to undergo surgery. Only 3.9% of patients underwent metastectomy, although it is unclear how many patients were eligible for this procedure.

Experts have advocated the use of the Preoperative Assessment of Cancer in the Elderly (PACE), a composite of validated questionnaires that includes the CGA, performance status, and assessments of surgical and anesthesia risks, to estimate risk for an individual elderly patient who is to undergo colorectal cancer surgery.7 In a pilot study, PACE took approximately 20 minutes to complete and was acceptable to patients.48,49 Performance status, activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and fatigue were significantly associated with general morbidity and performance status.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Older Patients with Colorectal Cancer

Adjuvant therapy is administered to eradicate potential residual micrometastatic disease following surgical resection. Adjuvant chemotherapy is considered standard of care for patients with stage III colon cancer based on improvement in overall 5-year survival rate from approximately 50% without adjuvant therapy to 65% with fluorouracil-based therapy after surgical removal of the primary tumor.50 More recently, the addition of a third agent, oxaliplatin, to fluorouracil plus leucovorin-based therapy has become the standard for stage III disease.51

Numerous studies have demonstrated that receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy varies substantially with age. A SEER database retrospective analysis by Schrag et al11 evaluated 6262 patients age 65 years and older with resected stage III colon cancer and found that age at diagnosis correlated more than any other factor to receipt of chemotherapy. A systematic review of 22 reports of the community rates of chemotherapy administration to patients with stage III colon cancer found significant variations in use, with rates of chemotherapy use ranging from 39% to 71%.12 In addition to receiving less chemotherapy, older persons are more likely to have adjuvant chemotherapy discontinued before completion, possibly decreasing its effectiveness. Dobie et al52 analyzed 3193 patients using the SEER-Medicare database and found that only 2497 (78.2%) completed the course of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Data for adjuvant therapy in elderly persons, although limited, suggest that older patients derive significant benefit from adjuvant therapies provided they have life expectancies of 5 years or more.53 Analyses of clinical trials that compare the outcomes of these generally “fit” patients age 70 and over with those younger than age 70 demonstrate similar efficacy and tolerability of adjuvant chemotherapy (Table III). A pooled analysis of 3351 elderly patients from seven clinical trials evaluated 5-FU–based adjuvant therapy for stage II/III disease.13 Chemotherapy was associated with a statistically significant effect on overall survival (hazard ratio [HR] 0.76) and time to recurrence (HR 0.68) when compared to surgery alone. Toxicity was not found to be significantly higher for those age 70 and over. However, patients age 70 and over had a 13% higher probability of death due to causes other than cancer as compared to 2% in those age 50 years or younger.

Less information is available regarding the adjuvant treatment of elderly patients using combination chemotherapy. The landmark Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin/5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of the Colon Cancer (MOSAIC) trial showed that the addition of adjuvant oxaliplatin to a hybrid regimen of bolus and infusional 5-FU provided a significant improvement in disease-free survival among high-risk stage II and any III patient.51 The upper age limit was 75 years, and only 14% of patients were between 70 and 75 years old. The FOLFOX regimen (bolus and infusional 5-FU, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) remains the backbone of adjuvant treatment today, although data for vulnerable older patients in the more general population are limited. A retrospective analysis of 3742 colorectal patients (614 age ≥ 70 yr) who received FOLFOX in the adjuvant, first-, and second-line settings within clinical trials found that the relative benefit of chemotherapy versus control was not impacted by age for progression or recurrence-free survival.54 Although hematologic (both neutropenia and thrombocytopenia) toxicity was higher in older patients, other toxicities such as neurologic events, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, infection, and overall grade 3 events were not significantly increased in the older patients. Although these data were promising, the older patients were a highly select group, representing only 16% of those enrolled within the clinical trials. Capecitabine, an oral prodrug of 5-FU, has been shown to be an effective and safe alternative for adjuvant therapy in elderly patients. A randomized study (Xeloda in Adjuvant Colon Cancer Therapy [X-ACT] trial) conducted by Twelves et al55 in 1004 patients showed similar disease-free and overall survival using capecitabine or bolus fluorouracil/leucovorin in patients with resected stage III colon cancer. Capecitabine showed superior relapse-free survival and fewer adverse effects and was subsequently approved as a single agent for adjuvant therapy. Data from the X-ACT trial was analyzed retrospectively for safety. Patients randomized to capecitabine had less diarrhea (P = 0.002), nausea (P = 0.005), and neutropenia (P < 0.00001). All grades of hand-foot syndrome and grade 3 or 4 hyperbilirubinemia were seen more with capecitabine.56

Treatment of Advanced Colorectal Cancer in the Older Patient

Despite a potentially higher risk of toxicity from chemotherapy in older patients, evidence indicates that fit elderly persons benefit from standard treatments for metastatic colon cancer similarly to younger patients. Until recently, bolus 5-FU and leucovorin was the standard of care. Current standard first-line therapies for fit elderly persons with good performance status include FOLFOX (bolus/infusional 5-FU and leucovorin with oxaliplatin) and/or FOLFIRI (bolus/infusional 5-FU and leucovorin with irinotecan) with or without bevacizumab. Although evidence suggests that these regimens are tolerable and efficacious for older persons with a good performance status, studies have shown that elderly patients are less likely to receive chemotherapy. One study that evaluated the management of advanced colorectal cancer in 10 community practices found that only 56% of elderly patients received first-line therapy.57 Of the younger patients, 84% received doublet chemotherapy first-line as compared with 58% of elderly patients (P < 0.001). The use of irinotecan, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab were all lower in elderly patients (P < 0.001). Independent predictors of a higher risk for mortality were age greater than 65 (HR 1.19) and poor performance status (HR 1.65).

Chemotherapy strategies and options for colorectal cancer have evolved rapidly in the past few years (Table III). Palliative treatment with the combination of fluorouracil with leucovorin, has been shown to improve response rates, time to progression, and overall survival in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with acceptable toxicity.58-60

More recently, several other cytotoxic and biologic agents have been used with improvements in survival in the metastatic setting.31 Irinotecan, as a single agent, has demonstrated clinical benefit as second-line treatment after fluorouracil failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.61,62 A study by Chau et al63 evaluated outcomes of 339 patients who had progressed on first-line 5-FU–based chemotherapy who received irinotecan as a single agent. Response rates and survival benefit were similar in elderly patients as compared to younger patients for irinotecan as a second-line agent. However, in this study also as well as others, irinotecan was shown to be associated with a high rate of diarrhea in elderly patients in the second-line setting, especially when given with bolus 5-FU rather than infusional administration.64,65

Combination chemotherapy with oxaliplatin has also been shown to be effective and safe for older patients. The FOLFOX regimen resulted in better response rates and prolonged time to progression than the fluorouracil (bolus plus 22-hr infusion every 2 wk) regimen for first-line treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.66 The dose-limiting toxicity of oxaliplatin was neurotoxicity, characterized by acute dysesthesias and a cumulative peripheral neurotoxicity, which is generally reversible with discontinuation of therapy. Sensory neuropathy generally occurs after cumulative doses of oxaliplatin of 700 mg/m2 and often requires discontinuation of the drug.67,68 More information is needed regarding the impact of neurotoxicity on quality-of-life indices important to the elderly, such as physical and functional performance.

Comorbidities, which increase in prevalence with age, such as chronic kidney disease are more important determinants of tolerance of chemotherapy than chronologic age. Chronic kidney disease influences chemotherapy treatment decisions, and formulas that estimate creatinine clearance from serum creatinine are often used is such patients. Pharmacokinetic studies have shown oxaliplatin plasma clearance to be proportional to creatinine clearance, raising the question of increased toxicity among patients with chronic renal dysfunction. A multi-institutional study sponsored in part by the National Cancer Institute provided important data regarding dosing in renal dysfunction, as defined by a 24-hour urinary creatinine clearance. Despite escalation of dose beyond that in the FOLFOX regimen, adminsitration of oxaliplatin monotherapy did not incur increased side effects among patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 20 mL/min.69 The frequency of oxaliplatin adminstered in this small cohort was identical to that used in the FOLFOX regimen. Unlike irinotecan, no dosing adjustment is required in the absence of severe renal dysfunction. A careful estimation of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine, using validated formulas such as the Cockroft-Gault and Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD), is especially important in this setting.

For elderly patients with advanced colorectal cancer who are deemed ineligible for combination approaches, capecitabine has been shown to be an effective and safe option.70 Dose-limiting side effects include diarrhea and hand-foot syndrome. Cassidy et al71 performed an analysis evaluating efficacy and toxicity of capecitabine in the elderly using data from two phase III studies (n=1207), which randomized 1207 patients to oral capecitabine versus intravenous fluorouracil/folinic acid as first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer.71 A poor safety profile was demonstrated in patients age 80 and over, mainly due to a higher incidence of grade III and IV gastrointestinal events. However, multivariate analysis revealed that age was not independently associated with adverse events from capecitabine. The toxicity of capecitabine in older patients was thought to be caused by age-related decline in renal function.72

The use of biologic agents including cetuximab and bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy has not been well studied in elderly populations.73 Use of cetuximab, an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor, combined with chemotherapy has shown improvement in response rates and progression-free survival when given as first-line treatment or after chemotherapy failure for metastatic colorectal cancer. It is fairly well tolerated, with the side effects being acne-like rash, infusion-related toxicity, and diarrhea.74 Subgroup analyses from randomized studies and retrospective analyses suggest that the efficacy of chemotherapy with cetuximab is maintained in fit elderly patients, with slightly increased but acceptable toxicity. Response to cetuximab has been shown to be related to the K-RAS mutation status, with response being almost exclusively seen in tumors with wild-type K-RAS as opposed to mutated K-RAS. Thus, the current available data support the use of cetuximab in fit elderly patients whose tumors are wild-type K-RAS.

Bevacizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), has demonstrated statistically significant improvements in response rates, progression-free, and overall survival when used with chemotherapy in various trials.75 Generally, studies have found that bevacizumab with chemotherapy is as safe and effective for elderly colorectal patients as in younger patients. However, bevacizumab is associated with side effects that require careful consideration in the elderly, including hypertension, proteinuria, bleeding, wound healing complications, and bowel perforation. Of particular importance is the risk of arterial thromboembolic events following bevacizumab, which may be more likely to occur in the elderly, especially in those who have had a previous history of such events as stroke or myocardial infarction.7 Kabbinavar et al76 examined the clinical benefit of bevacizumab plus fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer treatment in patients age 65 years and over, using data from two placebo-controlled clinical trials. Efficacy and safety data were analyzed for 439 patients age 65 years and older randomized to bevacizumab plus chemotherapy. Median overall survival was 19.3 months in the bevacizumab arm versus 14.3 months in the placebo-plus-chemotherapy arm. The incidence of arterial thromboembolic events of any grade was 7.6% in the bevacizumab-plus-chemotherapy group as compared to 2.8% in the placebo-plus-chemotherapy group. An analysis of data from 1745 patients who received bevacizumab plus chemotherapy for metastatic cancer found that older age and history of atherosclerosis were independent risk factors for the development of arterial thrombotic events.77 Overall, while benefits of bevacizumab are comparable in older patients to what is expected in younger patients, the toxicity profile differs slightly, and the risk of arterial thrombotic events with bevacizumab-containing regimens, while relatively low, may be higher in older patients than in younger patients, especially in those who have comorbidities.

In summary, given the current evidence, combination chemotherapy should be considered for fit, older patients. With little exception, fit elderly patients benefit to the same degree as younger patients from systemic chemotherapy. Bevacizumab can be used in elderly patients as first-line therapy in combination with chemotherapy with careful selection of patients so that this treatment can be avoided in those with history of stroke, heart disease, or severe hypertension. For those who are more vulnerable, single agent 5-FU or capecitabine can be considered. 5-FU continuous infusion has been shown to be more effective and less toxic than bolus 5-FU. Special attention to renal function with dose reduction according to creatinine clearance should be undertaken.

Conclusion

Colorectal cancer can be considered a disease of the elderly, with a median age of diagnosis of 72 years. In addition to incidence and mortality, older age also is associated with differences in outcomes from colorectal cancer. There is considerable variation within the elderly subpopulation with regards to receipt of screening, surgery, and chemotherapy for early or advanced-stage disease. These differences in patterns of care may be a result of underlying differences in the health status of older persons, which preclude some from receiving aggressive “standard of care” approaches for their disease. CGA could be used to help with differentiating older fit persons who have been shown to benefit as much as their younger counterparts for treatment of colorectal cancer from those who are more vulnerable or frail.

The majority of patients with early-stage colon cancer are cured with surgery. Adjuvant chemotherapy improves outcomes for those persons who present with higher-risk stage II or stage III cancers. The standard treatment for advanced colorectal cancer includes chemotherapy either alone or in combination with targeted therapies. Surgical removal of the primary lesion or metastatic lesions in the advanced disease setting is an option for those that are “fit” and have limited metastatic disease. In general, if treatment is deemed palliative, the most active chemotherapy option with the least toxicity should be considered to improve quality of life and prolong survival. However, if cure is a possibility, higher levels of toxicity due to more aggressive chemotherapy approaches may be deemed acceptable.7 A multidisciplinary team, preferably including a trained geriatrician or geriatric oncologist to help determine underlying fitness for treatment, should define each patient’s treatment plan at presentation. In addition, clinical trials with multidisciplinary input that evaluate treatment approaches for older, more vulnerable patients with colorectal cancer are necessary.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Drs. Mongan, Peppone, and Mohile are from the James P. Wilmot Cancer Center, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY; and Dr. Kalady is from the Department of Colorectal Surgery, Digestive Disease Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH. Dr. Suh is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, Staff in the Section of Geriatrics, The Cleveland Clinic, and Medical Director of the Geriatric Assessment Program, Euclid Hospital, Cleveland, OH.