Premature Thelarche

A 16-month-old African American girl presented to clinic with her parents for a routine checkup. On physical examination, her height and weight were in the 98th and 100th percentiles, respectively, which were similar to prior measurements. Bilateral premature thelarche (Tanner stage 3) was present, but no other signs of secondary sexual development or birthmarks were observed (Figures 1 and 2).

The father stated that the girl and her older sister have had progressive enlargement of their breasts since birth; the patient’s 3-year-old sister’s premature thelarche was now resolving (Figure 3). The patient’s mother reportedly “wore a bra in kindergarten,” and the father reported having “breasts” as a toddler. The girl’s dietary history was negative for consumption of soy products or other phytoestrogens, and there were no prescribed medications, specifically estrogens, in the home.

Premature thelarche, a transient and nonprogressive condition defined by isolated breast development in girls, occurs before 8 years of age. The 2 peak ages are the first 2 years of life and after 6 years of age. The diagnosis cannot be made if other pubertal signs are present, such as accelerated growth, pubic or axillary hair, or menstrual bleeding.

It may be difficult to differentiate breast tissue from adipose tissue in children who are overweight or obese; however, careful palpation of the chest reveals a homogeneous mass beneath the areola with breast tissue, whereas adipose tissue does not. Some call this the “doughnut sign.”1

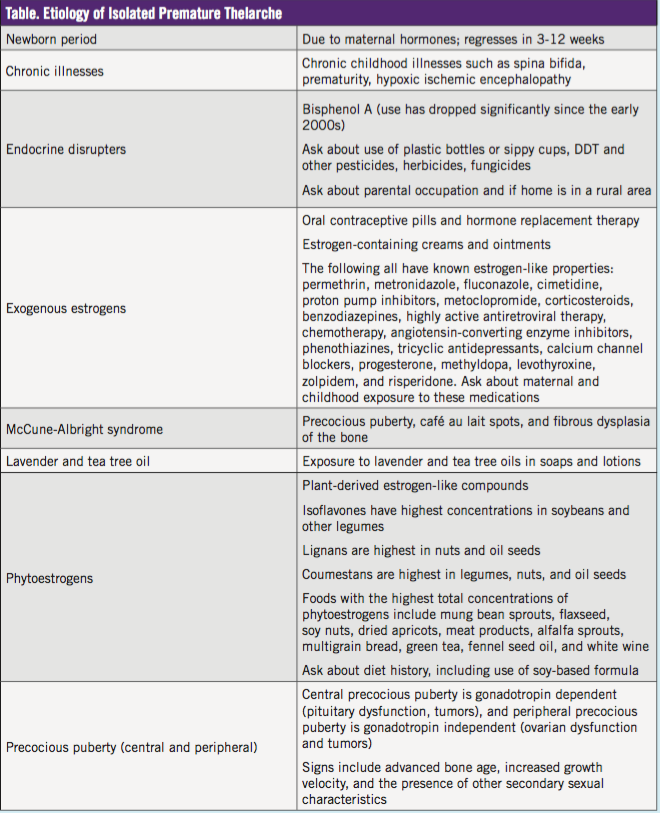

The etiology of isolated premature thelarche is diverse (Table) and can be associated with chronic illness, endocrine disrupters that mimic natural hormones, exogenous estrogens, phytoestrogens, and lavender oil.2-5 Also, premature thelarche can herald the onset of precocious puberty.6

When patients present with premature thelarche, it is important to ask about phytoestrogens in the diet (eg, soy formula or soy milk, flaxseed, fennel tea) and medications in the home that may expose the child to estrogen (eg, hormonal contraceptives, estrogen creams), and to advise parents to watch for the development of other signs of puberty such as axillary hair or pubic hair.

If other signs of puberty are present before 8 years of age, referral to a pediatric endocrinologist is indicated.

The appropriate amount of testing (blood work and imaging) and follow-up required is controversial. A recent retrospective study7 looked at 275 children younger than 3 years with signs of early puberty. Of these children, 156 (57%) were diagnosed with premature thelarche, and all had normal luteinizing hormone (LH) and estradiol levels. Of the children in the study, 69 (25%) had genital hair of infancy (GHI), and 37 (13%) had both premature thelarche and GHI. Six of the children had axillary odor. Four children had more serious diagnoses, including congenital adrenal hyperplasia in 2 children, McCune-Albright syndrome in 1 child, and central precocious puberty in 1 child with cerebral palsy.7

The key findings in children with premature thelarche are normal linear growth and lack of progression of puberty over time. Clinicians may forgo laboratory testing and opt for regular follow-up for at least 1 year. Testing for bone age, estradiol and LH levels, and a referral to an endocrinologist are indicated for growth acceleration or the development of other signs of puberty.

Holly Smith, MD, is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

John Gray, BS, is a medical student at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston.

Michael Yafi, MD, is associate professor and director of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston.

Lynnette Mazur, MD, MPH, is a professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston.

References

1. Blum A Jr. The doughnut sign. Pediatrics. 1990; 86(6):1001.

2. Paris F, Gaspari L, Servant N, Philibert P, Sultan C. Increased serum estrogenic bioactivity in girls with premature thelarche: a marker of environmental pollutant exposure? Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(8):788-792.

3. Thompson LU, Boucher BA, Liu Z, Cotterchio M, Kreiger N. Phytoestrogen content of foods consumed in Canada, including isoflavones, lignans, and coumestan. Nutr Cancer. 2006;54(2):184-201.

4. Okdemir D, Hatipoglu N, Kurtoglu S, Akin L, Kendirci M. Premature thelarche related to fennel tea consumption? J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27(1-2):175-179.

5. Linklater A, Hewitt JK. Premature thelarche in the setting of high lavender oil exposure. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51(2):235.

6. Berberoğlu M. Precocious puberty and normal variant puberty: definition, etiology, diagnosis, and current management. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2009;1(4):164-174.

7. Kaplowitz PB, Mehra R. Clinical characteristics of children referred for signs of early puberty before age 3. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015;28(9-10):1139-1144.