Peer Reviewed

Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis

Authors:

Pooja Pundhir, MD, MPH; Taban Ghaffaripour, MD; Monica A. Recine, MD; and Claudio Tuda, MD

Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, Florida

Citation:

Pundhir P, Ghaffaripour T, Recine MA, Tuda C. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis. Consultant. 2017;57(6):380-381.

An 83-year-old woman presented with pustular lesions that had developed over her right knee and had progressively worsened over the past week. She reported having fallen on her knees in her garden 2 weeks prior to symptom onset. She did not have fever, chills, or other systemic symptoms.

History. The patient’s medical history was pertinent for hypertension and rheumatoid arthritis, the latter of which had been controlled with methotrexate and infliximab for the past 5 years. She denied any recent contact with animals, insect bites, and participation in water activities or other outdoor sports.

Physical examination. On examination, the patient did not appear toxic and had normal vital signs. The skin over the right knee was erythematous and tender, with multiple draining pustular lesions, one of which was covered with eschar (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. No subcutaneous gas was palpated, and peripheral pulses were intact. There was no passive or active limitation of knee joint mobility.

Diagnostic tests. Results of a complete blood cell count and a metabolic panel were normal, and blood culture results were negative for pathogens. Radiographic findings of the right knee were also normal.

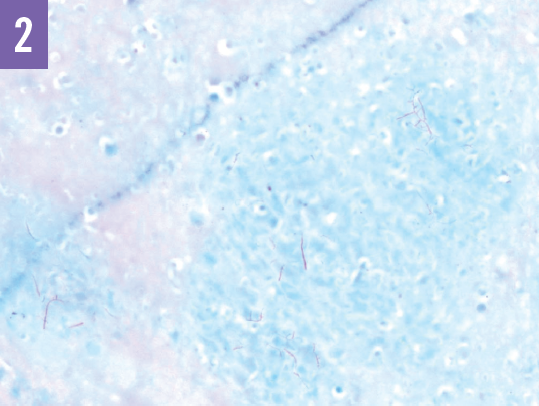

The patient underwent drainage of the skin abscess and bursa. Branching, beaded, weakly gram-positive, filamentous rods were identified on Gram stain of the exudate. Fite stain of the exudate revealed acid-fast branching filaments (Figure 2). Wound culture test results confirmed the presence of Nocardia species.

Discussion. Nocardia species are aerobic gram-positive rods that are ubiquitous in the environment, found in soil, vegetation, and water. Nocardia species are usually innocuous in otherwise healthy human hosts, but they can cause life-threatening granulomatous infections in immunocompromised persons.1 Classic risk factors include HIV infection, long-term corticosteroid therapy, the use of immunosuppressants and chemotherapy, and diabetes mellitus, among many others.1,2 With the growing number of patients over the past 20 years who are on biological agents that modulate tumor necrosis factor-α activity, reports of the primary cutaneous form of indolent, resistant nocardiosis in this patient population have also increased.2-5

Direct inoculation of Nocardia through penetrating trauma results in a slowly progressing cellulitis. In addition to infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes—the usual culprits in this context—other potential differential diagnoses include mycobacterial infection, actinomycosis, erysipeloid, and sporotrichosis and other fungal infections.1 If allowed to spread, nocardiosis can disseminate into fulminant pulmonary, cerebral, or systemic disease.

Strong clinical suspicion of nocardiosis is imperative and can expedite the diagnosis and prompt treatment. Visualization of branching gram-positive rods on Gram stain and filamentous acid-fast bacteria are the initial microbiologic clues that should prompt specific culture media and prolonged incubation.

Nocardia species are susceptible to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).1 Extended therapy for 3 months to a year (oral or parenteral) may be warranted depending on the severity of infection.2

Outcome of the case. Abscess drainage and concomitant regimen of high-dose TMP-SMX for 3 months resulted in resolution of the patient’s lesions.

REFERENCES:

- Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(4):403-407.

- Abreu C, Rocha-Pereira N, Sarmento A, Magro F. Nocardia infections among immunomodulated inflammatory bowel disease patients: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(21):6491-6498.

- Fabre S, Gibert C, Lechiche C, Jorgensen C, Sany J. Primary cutaneous Nocardia otitidiscaviarum infection in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(12):2432-2433.

- Kofteridis D, Mantadakis E, Mixaki I, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis in 2 patients on immunosuppressants. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37(6-7):507-510.

- Bogaard HJ, Erkelens GW, Faber WR, de Vries PJ. Cutaneous nocardiosis as an opportunistic infection [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2004;148(11):533-536.