Quality Improvement in the Diagnosis and Management of Diabetes Mellitus in Older Adults

This article is the second in a continuing series on diabetes in the elderly. The first article in the series, “Pathophysiology of Diabetes in the Elderly,” was published in the April issue of the Journal. The remaining articles in the series will discuss such topics as the role of exercise and dietary supplements in the management of diabetes, treatment of diabetes with oral and parenteral agents, as well as microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes.

Introduction to Quality Improvement Efforts

Diabetes mellitus is a prevalent, chronic disease in older adults, often accompanied by cardiovascular comorbid conditions that lead to functional impairments and disabilities.1 Twelve million adults age 60 years and older were estimated to have diabetes in 2007.2 American adults with diagnosed diabetes is expected to increase by 165% by 2050, with the largest percent increase among those age 75 years or older.3

Despite the prevalence of diabetes and the availability of effective treatment, many adults of all ages with diabetes do not receive all of the care shown or considered to be associated with improved outcomes, defined as decreased cardiovascular and microvascular complications.4,5 Efforts to improve the quality of diabetes care have been ongoing for the past decade, and different quality performance measures have been investigated and promulgated. Establishing quality-of-care guidelines and measures for older adults with diabetes has the added difficulty that high-quality diabetes studies frequently do not include substantial numbers of older adults. Thus, evidence supporting the appropriateness of commonly used quality measures for the older adult population is often lacking. While specific treatment targets for older adults remain debatable, diabetes is a severe disease, and physicians must prioritize its treatment. Available quality measures can help physicians keep track of the multiple components of care associated with high-quality diabetes management.

Development of Diabetes Quality Performance Measures

In response to the need to improve the quality of diabetes care, the Diabetes Quality Improvement Project (DQIP) was formed, with support from more than 25 key organizations, including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA),6 the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. In 1997, the DQIP developed a set of quality performance measures for diabetes care so that quality of care could be assessed in a standardized manner.7 Variations of these performance measures have been adapted and incorporated into the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), the ADA Diabetes Physician Recognition Program, the American Medical Association (AMA) Diabetes Mellitus Measures Group, and the VHA performance monitoring program, among others.

The DQIP partners continued their work through the National Diabetes Quality Improvement Alliance (NDQIA). The NDQIA integrated diabetes measures provided by the AMA-Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA-PCPI),8 and these measures have been endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF),9 which continues to promote the use of a set of updated standardized measures to assess the quality of diabetes care.

Structure of Quality Performance Measures

Quality performance measures include both: (1) process measures; and (2) outcome measures. Process measures typically reflect guidelines of care for patients with diabetes, such as the frequency with which a provider measures a patient’s blood pressure (BP), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), or lipid levels. Ideally, improvement in each process measure leads to improvement in associated outcome measures. Outcome measures may be intermediate or long term. Intermediate outcome measures for diabetes, including BP, HbA1c, and lipid levels, are usually the quality performance measures because they have been shown to be correlated with long-term outcomes. Long-term outcomes, including cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and mortality, have a long lag period between the provision of care and the outcome itself, so are not ideal for quality-of-care assessment over the short term.

Quality measures are often rates, indicating the percentage of the eligible population achieving a preset goal. Measures are based on guidelines developed by professional organizations (eg, ADA, American Geriatrics Society [AGS]). Oldest-old adults (> 75 yr) are often not eligible for diabetes performance measures. For example, the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) currently defines the eligible population for diabetes quality measures as adults 18-75 years of age only.10 Providers also have the option of excluding individual patients from quality measures if providers believe that specific measures should not apply to these patients or if other considerations have greater priority (eg, end-of-life care). Current quality performance measures for diabetes do not adjust for the medical complexity of individual patients (ie, do not case-mix adjust).

Quality Performance Measures in Current Practice

Quality of care can be measured by the performance of an individual provider or a health plan. The PQRI, established by CMS in 2007 and using measures endorsed by the NQF, is a reporting system of individual physician quality performance.10 The HEDIS measures, designed by NCQA, are the most widely collected performance indicators to assess the performance of health plans.6 Quality measures have been implemented in different ways: providers self-report data to health plans; health plans perform audits via medical chart reviews and/or administrative data reviews; and patients are surveyed for satisfaction in their diabetes care.

Over the past decade, large numbers of diabetes performance measures have been developed by different health organizations. Organizations such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),11 NQF, and AMA-PCPI are attempting to unify these measures into a single standardized set.

Standardized quality measures enable individual providers, health plans, and consumers/patients to compare the quality of care of different health plans and providers.12 For example, because many plans collect HEDIS data, HEDIS permits the comparison of health plan performance on an “apples-to-apples” basis. Many health plans report HEDIS data to employers and use HEDIS results to indicate where the plans should focus improvement efforts in care and service.

Quality measures are also used in incentive programs to reward individual providers and health organizations for providing good healthcare. For example, providers who satisfactorily submit PQRI quality measures data during the 2010 reporting period will qualify to earn an incentive payment.10

The quality of care provided by providers and healthcare organizations is most easily assessed when patients receive all of their medical care from a single provider or healthcare organization. However, under Medicare fee-for-service, patients frequently receive care from multiple providers and/or healthcare organizations. Further, providers can select which quality measures (out of the entire set of quality measures) to report to PQRI. Thus, the true quality of care provided by individual providers can be difficult to determine.

Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus

The 1999-2002 National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that 19.3 million adults (9.3% of the entire U.S. population) had diabetes mellitus, one-third of whom were undiagnosed.13 Because hyperglycemia develops gradually and is typically asymptomatic, type 2 diabetes frequently remains undiagnosed for many years. Adults with newly-diagnosed diabetes already have an increased prevalence of macrovascular disease.14,15

Valid and reliable tests can detect type 2 diabetes at its early phase.16 The ADA now recommends screening adults who may be at high risk for development of diabetes; for adults without risk factors, screening should begin at 45 years old and be repeated at least every three years.17 High-quality modeling studies suggest that targeted screening of adults with hypertension may be relatively cost-effective, with macrovascular benefits in older adults.18,19 Both targeted and universal diabetes screening were more cost-effective for adults age 55 years and older as compared to younger adults. Screening for diabetes is not included in PQRI quality measures for 2010.10

A population study suggests a persistent high rate of undiagnosed diabetes from 1988-1994 and from 2005-2006; 43% of adults 60-74 years of age with diabetes were undiagnosed in 2005-2006, as compared to 49% in 1988-1994.20 This may be due in part to the revised criteria for diabetes diagnosis in 1997, when ADA lowered the fasting plasma glucose level for diabetes diagnosis from ≥ 140 mg/dL to ≥ 126 mg/dL.21 Studies are needed to evaluate the change in diabetes diagnosis rates after 1997 and among adults at high risk for development of diabetes, including older adults.

Management of Diabetes Mellitus

In helping to develop diabetes management plans for older adults, providers need to consider patients’ age, social situation, physical activity, and comorbidity burden, including the presence of diabetes complications.

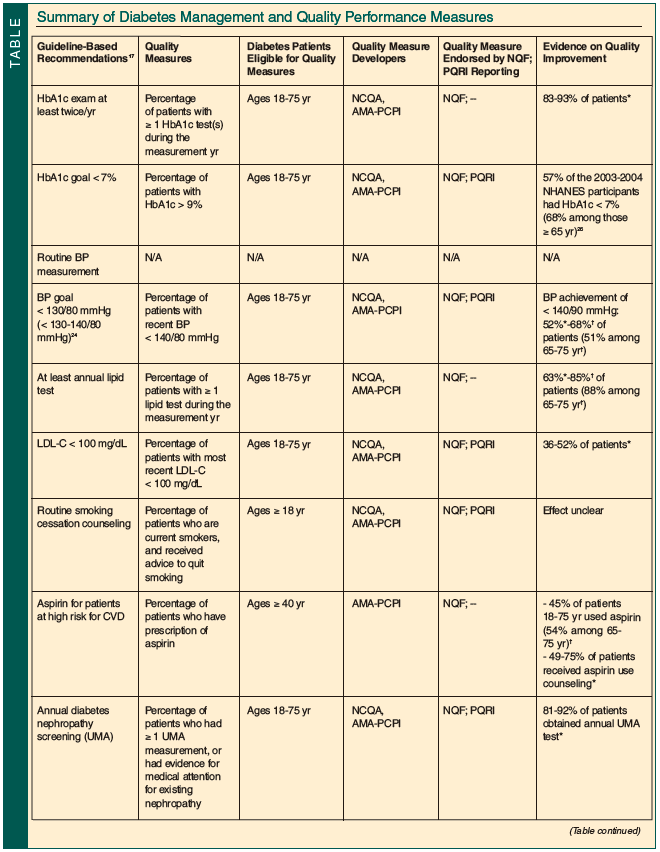

The Table summarizes quality performance efforts in the management of diabetes based on general guidelines developed by medical organizations such as ADA. The age of the eligible patient population for each measure is highlighted in the Table. As the focus of the current article is on diabetes care for older adults, the quality measures described were primarily developed by NCQA and AMA-PCPI, endorsed by NQF, and adopted by CMS in PQRI. It is beyond the scope of this article to address all quality measures developed and used by different healthcare providers and purchasers.

Evidence for diabetes care performance reviewed in this article is largely from two studies. Saaddine et al2 compared the change in quality of diabetes care among adults 18-75 years of age in the United States from 1988-2002, using two national population-based studies—NHANES and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Kerr and colleagues23 compared the quality of diabetes care between patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system and those enrolled in the commercial managed care (CMC) organizations. The average age of the participants from the VA was 65.1 ± 10.5 years and was 61.4 ± 13 years from CMC.

Hyperglycemia Management

HbA1c has strong predictive value for diabetes complications. Quality performance measures for glycemic control target: (1) the frequency of measuring HbA1c; and (2) actual HbA1c levels. The ADA recommends routine HbA1c testing in all patients with diabetes—quarterly in patients not meeting glycemic goals or whose therapy has changed, and at least twice each year in all others.17 Quality measures typically assess the percentage of patients having at least one HbA1c test annually.12 Both the VA system and CMC have demonstrated high levels of annual HbA1c testing: 93% and 83%, respectively.23

HbA1c values < 7% are commonly the target, 17 as this level has been shown to reduce microvascular and neuropathic diabetes complications. However, less stringent HbA1c goals may be appropriate for selected patients, including those with severe hypoglycemia, limited life expectancy, or extensive comorbid conditions. The AGS recommends that physicians individualize the HbA1c goal for older adults: ≤ 8% for those with poor physical function and/or life expectancy less than 5 years; and ≤ 7% for all others.24

While the guidelines recommend targeting a specific low HbA1c level, performance measures often focus on patients having high HbA1c levels. For example, HEDIS and PQRI measure the proportion of adults having HbA1c > 9%.6,10

Diabetes quality improvement efforts on glycemic control appeared to be effective in reducing HbA1c values. In a meta-regression analysis, Shojania et al25 found that HbA1c values were reduced by a mean of 0.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.3-0.5%) over a median of 13 months of follow-up. Among adults 65+ years of age, the mean HbA1c levels declined from 7.5% in 1999-2000 to 7.0% in 2001-2002 and 6.7% in 2003-2004 in NHANES participants with diabetes.26

Blood Pressure Management

The optimal BP goal for patients with diabetes is widely debated. The American College of Physicians (ACP) recommends a BP goal of 130-135/80 mmHg for patients with diabetes.27 The ADA and the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure recommend BP < 130/80 mmHg.17,28 The AGS recommends targeting BP < 130-140/80 mmHg if tolerated by the older adult24 Recent findings from the Action to Control CardiOvascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial29 suggest that systolic BP < 120 mmHg (vs < 140 mmHg) may not provide greater cardiovascular protection.

The disagreements in BP goals are reflected in performance measures: HEDIS measures proportion of patients age 18-75 years with diabetes whose most recent BP was < 130/80 mmHg and < 140/90 mmHg6 whereas the PQRI measures patients whose most recent BP was < 140/80 mmHg.10

Data from NHANES and BRFSS participants with diabetes suggest that BP control has not substantially improved from the 1990s to the 2000s.22 Suboptimal BP control has also been noted in VA and CMC patient populations.23

Lipid Management

Quality performance measures of lipid management target the proportion of patients: (1) having at least one low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) test each year; and (2) achieving a specific LDL-C level. From the 1990s to the 2000s, the annual assessment of lipid profile has improved significantly by 7% (95% CI, 0.5-13.1) from a baseline of 81% among patients 65-75 years of age with diabetes.22

The ACP recommends that lipid-lowering therapy be used for secondary prevention of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity for all patients with type 2 diabetes and that statins be used for primary prevention.30 The ADA recommends the LDL-C goal of < 100 mg/dL for individuals without overt CVD.17 The ADA has also made recommendations for target high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL; > 40 mg/dL) and triglycerides (< 150 mg/dL), although these have not been incorporated into quality performance measures.

The HEDIS measures and the PQRI report the proportion of patients with LDL-C < 100 mg/dL6,10; use of statins is not routinely reported. Fifty-two percent of VA patients and 36% of CMC patients achieved a LDL-C < 100 mg/dL.23 Data from NHANES and BRFSS demonstrated substantial improvement in the proportion of adults with diabetes achieving LDL-C < 100 mg/dL (Table); HDL cholesterol and triglycerides did not show improvement.22

Lifestyle Interventions: Physical Activity and Nutrition

Regular exercise improves blood glucose control, reduces cardiovascular risk factors, and contributes to weight loss. Neither HEDIS nor PQRI have specific measures on physician recommendation of physical activity for patients with diabetes. The NQF endorses the NCQA measure on physician assessing and advising adults 65 years of age or older (with or without diabetes) about physical activity.12 Of adults 65 years of age or older with diabetes surveyed in NHANES III (1988-1994), 77% reported no regular physical activity or less than the recommended levels of physical activity.31 In 2003, over 40% of adults 60-79 years of age with diabetes in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey reported being physically inactive.32

The ADA recommends individualized medical nutrition therapy, as it may improve outcomes and cost.17 The 2010 PQRI and AMA-PCPI measures did not include measures on nutrition counseling. Fifty-six percent of adults 65 years of age or older in NHANES III consumed > 30% of daily calories from fat, and 51% consumed fewer than five daily servings of fruits and vegetables.31 Efforts to improve physical activity and nutrition among older adults with diabetes are urgently needed.

Smoking Cessation

Approximately 12% of adults with diabetes who are 65 years of age or older smoke. Following cessation of smoking for two to three years, their increased risk for CVD appears to decline to levels of nonsmokers.24 The ADA recommends that smoking cessation counseling and other treatments be a routine component of diabetes care.17

The HEDIS and PQRI both measure the proportion of patients who smoked and received smoking cessation advice.6,10 This is a general preventive healthcare measure, not targeting patients with diabetes. In 2007, 70-76% of patients who smoked were advised to stop smoking, and 39-51% were advised on smoking cessation medications; these results appeared to be moderately improved as compared to 2003.

The efficacy of smoking advice has been demonstrated in a number of studies in the general population.3 The proportion of patients with diabetes who are current smokers has not changed from the 1990s to the 2000s, although more smokers have indicated that they are trying to quit smoking (43% vs 62% from 1990s to 2000s).22

Antiplatelet Agents

There is strong evidence supporting the use of aspirin for secondary prevention in diabetes patients with CVD. Currently, the ADA recommends aspirin therapy in adults with diabetes at increased cardiovascular risk (10-yr risk > 10%).17

Use of antiplatelet agents is currently not included in PQRI performance measures for patients with diabetes but is endorsed by NQF and AMA-PCPI (daily aspirin ≥ 75 mg) for adults older than 40 years of age.8,9 The proportion of adults 18-75 years of age with diabetes, with unclear cardiovascular risk, who used aspirin therapy has significantly improved from 32% to 45% from the 1990s to 2000s, although the improvement was not significant among those 65-75 years of age.2

Diabetes Nephropathy: Screening and Management

Diabetes nephropathy occurs in 20-40% of patients with diabetes and is the single leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The ADA recommends annual testing to assess urine microalbumin (UMA) excretion and to estimate glomerular filtration rate, and recommends treating UMA with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers.17

The PQRI reports the annual percentage of patients 18-75 years of age with diabetes who received urine protein screening or medical attention for nephropathy. Patients from both the VA and CMC received a high rate of annual UMA assessment: 92% and 81%, respectively.23 Data from the United States Renal Data System and the National Health Interview Survey suggested that the incidence of ESRD due to diabetes was unchanged from 1990 to 2002 among adults 65-74 years of age but increased by 10% for those 75 years of age or older.34

Diabetes Retinopathy: Screening and Management

Diabetes retinopathy is a leading cause of new cases of blindness among adults age 20-74 years. Tight blood glucose control is important to prevent and/or delay the onset and progression of diabetes retinopathy, and laser photocoagulation surgery has established efficacy in preventing vision loss. As such, the ADA recommends an annual dilated and comprehensive eye examination for adults with diabetes by an ophthalmologist or optometrist, so that they may be promptly referred for possible laser photocoagulation therapy.17

Annual dilated eye exams to screen for diabetes retinopathy are part of the diabetes quality measures. Patients 18 years of age or older are eligible for this measure. The proportion of adults 65-75 years of age with annual dilated eye exam has shown a modest improvement from 67.1% to 74%.22

Diabetes Neuropathy and Foot Care: Screening and Management

The most common manifestation of diabetes neuropathy is distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSP) and autonomic neuropathy. Effective symptom treatments are available for the underlying nerve damage, and knowledge of the neuropathy can promote better glycemic control and close monitoring to prevent insensate injury to the feet.

ADA recommends annual screening for DSP, using tests such as pinprick sensation, vibration perception, or 10-g monofilament pressure sensation. ADA also recommends annual comprehensive foot examination to identify risk factors predictive of ulcers and amputations by inspection, assessment of foot pulses, and testing for loss of protective sensation.17

The PQRI adopted measures developed by the American Podiatric Medical Association and NCQA, and assessed the percentage of adults with diabetes who had a foot examination, a neurological examination of their lower extremities within 12 months, and were evaluated for proper footwear and sizing. Population studies found modest improvement in foot exam among adults age 65-75 years from 1990s to 2000s (ie, 63.7% to 71.0%, respectively).22Studies are needed to confirm improvement in that frequency of foot exams are leading to decreased foot injuries related to diabetes neuropathy.

Diabetes Self-Management Education

Diabetes self-management is an essential component of diabetes care. Education in diabetes self-management has been shown to be effective in improving clinical outcomes and quality of life in the short term. Nonetheless, most patients with diabetes receive no formal education about managing their disease.35

To promote quality self-management programs, the National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education was established in 2006.35 Assessment of patient participation in diabetes self-management education is not routinely part of the performance measures; the 2010 PQRI and the AMA-PCPI measures do not include any measures for diabetes self-management education. Evaluation of patients’ perceptions of self-management support primarily exist in research settings.36

Only 55% of participants 18-75 years of age in the 2002 BRFSS reported receiving diabetes education.22 However, the proportion of participants who reported monitoring their blood glucose levels at least once daily increased from 38.5% in the 1990s to 55% in the 2000s, which may indicate improvement in diabetes education efforts.

Implications of Quality Performance Measures for Older Adults

Quality improvement programs appear to have led to improvement in diabetes care, particularly the processes of care.22 However, the achievement of intermediate outcomes remains suboptimal: 20% of adults with diabetes have poor glycemic control; 33% have poor BP control; and 40% have poor LDL-C control.37 These findings have led to recommendations for disease management programs to prioritize improving these intermediate diabetes outcomes. Furthermore, evidence is needed to determine the value of these quality measures in the oldest-old adults and in those with complex health conditions, as they are currently being excluded from these measures.

Current quality measures have been developed from studies of single-disease management; they are not case-adjusted for the complex health conditions common in the older adult population. Among Medicare beneficiaries age 65 years and older, 48% have at least three chronic medical conditions.38 Further, older adults with diabetes are at greater risk for common geriatric syndromes, such as cognitive impairment, urinary incontinence, and injurious falls.24 Older adults are heterogeneous in their functional status and comorbidity burden. Some older adults remain highly functional beyond the age of 75 years. Thus, it may not be appropriate to exclude adults in this age group from quality improvement efforts. In contrast, the current diabetes quality measures may not be appropriate for those older adults with multiple comorbidities and/or geriatric syndromes.39

There are continuing efforts to change the current single-disease–focused quality measures to address the different needs of older adults.24 Individual providers presently have the option to exclude from quality measures those individual patients whom the providers believe are not appropriate for the quality indicators or for whom other considerations take precedence. Mechanisms are needed to evaluate the quality of care in adults excluded from the standard quality measuring process. The need remains for quality performance measures that reflect the complex health status of older adults. In addition, efforts need to focus on improving diabetes outcomes, as well as processes of care.

Drs. Lee and Blaum are from the Department of Internal Medicine, and Dr. Cigolle is from the Departments of Family Medicine and Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. All authors are also from the Ann Arbor VA Healthcare System Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC).

Acknowledgments

Dr. Lee was supported by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at the University of Michigan, the Ann Arbor VA Healthcare System Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), and the John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence in Geriatrics at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Cigolle was supported by the NIH-NCRR KL2 Mentored Clinical Scholars Program at the University of Michigan, the Ann Arbor VA GRECC, and the John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence in Geriatrics at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Blaum was supported by the Ann Arbor VA GRECC.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Gregg EW, Beckles GL, Williamson DF, et al. Diabetes and physical disability among older U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 2000;23(9):1272-1277.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: General information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2007. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf.ndfs_2007.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2010.

3. McBean AM, Li S, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ. Differences in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality among the elderly of four racial/ethnic groups: Whites, blacks, hispanics, and asians. Diabetes Care 2004;27(10):2317-2324.

4. Saaddine JB, Engelgau MM, Beckles GL, et al. A diabetes report card for the United States: Quality of care in the 1990s. Ann Intern Med 2002;136(8):565-574.

5. Saydah SH, Fradkin J, Cowie CC. Poor control of risk factors for vascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed diabetes. JAMA 2004;291(3):335-342.

6. The State of Health Care Quality 2008. National Committee for Quality Assurance. http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Newsroom/SOHC/SOHC_08.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2010.

7. Fleming BB, Greenfield S, Engelgau MM, et al. The Diabetes Quality Improvement Project: moving science into health policy to gain an edge on the diabetes epidemic [published correction appears in Diabetes Care 2002;25(1):249]. Diabetes Care 2001;24(10):1815-1820.

8. Clinical performance measures, adult diabetes: Tools developed by physicians for physicians. Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/370/diabetesset.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2010.

9. National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Adult Diabetes Care: 2005 Update. National Quality Forum. http://www.qualityforum.org/Measures_List.aspx#k=diabetes&e=1&st=&sd=&s=&p=1. Accessed April 9, 2010.

10. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2010 PQRI measure list. Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI). http://www.cms.gov/PQRI/. Modified November 19, 2009. Accessed April 9, 2010.

11. Kerr EA. Assessing quality of care for diabetes. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/diabetescare/. Accessed April 9, 2010.

12. National Committee for Quality Assurance. http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/58/Default.aspx. Accessed February 26, 2010.

13. Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population: National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Diabetes Care 2006;29(6):1263-1268.

14. Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Haffner SM, et al. Elevated risk of cardiovascular disease prior to clinical diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25(7):1129-1134.

15. Meigs JB, Nathan DM, Wilson PW, et al. Metabolic risk factors worsen continuously across the spectrum of nondiabetic glucose tolerance. The Framingham Offspring Study. Ann Intern Med 1998;128(7):524-533.

16. Harris R, Donahue K, Rathore SS, et al. Screening adults for type 2 diabetes: A review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2003;138(3):215-229.

17. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2010 [published correction appears in Diabetes Care 2010;33(3):692]. Diabetes Care 2010;33(suppl 1):S11-S61.

18. Hoerger TJ, Harris R, Hicks KA, et al. Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med 2004;140(9):689-699.

19. Waugh N, Scotland G, McNamee P, et al. Screening for type 2 diabetes: Literature review and economic modelling. Health Technol Assess 2007;11(17):iii-iv, ix-xi, 1-125.

20. Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the U.S. population in 1988-1994 and 2005-2006. Diabetes Care 2009;32(2):287-294. Published Online: November 18, 2008.

21. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 1997;20(7):1183-1197.

22. Saaddine JB, Cadwell B, Gregg EW, et al. Improvements in diabetes processes of care and intermediate outcomes: United States, 1988-2002. Ann Intern Med 2006;144(7):465-474.

23. Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and commercial managed care: The TRIAD study. Ann Intern Med 2004;141(4):272-281.

24. Brown AF, Mangione CM, Saliba D, Sarkisian CA; California Healthcare Foundation/American Geriatrics Society Panel on Improving Care for Elders with Diabetes. Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51(5 suppl guidelines):S265-S280.

25. Shojania KG, Ranji SR, McDonald KM, et al. Effects of quality improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes on glycemic control: A meta-regression analysis. JAMA 2006;296(4):427-440.

26. Hoerger TJ, Segel JE, Gregg EW, Saaddine JB. Is glycemic control improving in U.S. adults? Diabetes Care 2008;31(1):81-86. Published Online: October 12, 2007.

27. Snow V, Weiss KB, Mottur-Pilson C; Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians. The evidence base for tight blood pressure control in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 2003;138(7):587-592.

28. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Commission on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003;42(6):1206-1252.

29. The ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus [published online ahead of print March 14, 2010]. N Engl J Med.

30. Snow V, Aronson MD, Hornbake ER, et al; Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians. Lipid control in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2004;140(8):644-649.

31. Nelson KM, Reiber G, Boyko EJ; NHANES III. Diet and exercise among adults with type 2 diabetes: Findings from the third National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Diabetes Care 2002;25(10):1722-1728.

32. Morrato EH, Hill JO, Wyatt HR, et al. Physical activity in U.S. adults with diabetes and at risk for developing diabetes, 2003. Diabetes Care 2007;30(2):203-209.

33. Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(2):CD000165.

34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Incidence of end-stage renal disease among persons with diabetes--United States, 1990-2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54(43):1097-1100.

35. Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care 2009;32(suppl 1):S87-S94.

36. Glasgow RE, Whitesides H, Nelson CC, King DK. Use of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) with diabetic patients: Relationship to patient characteristics, receipt of care, and self-management. Diabetes Care 2005;28(11):2655-2661.

37. Mangione CM, Gerzoff RB, Williamson DF, et al; TRIAD Study Group. The association between quality of care and the intensity of diabetes disease management programs. Ann Intern Med 2006;145(2):107-116.

38. Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep 2004;119(3):263-270.

39. Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: Implications for pay for performance. JAMA 2005;294(6):716-724.