Retropharyngeal Abscess Causing Airway Compromise

A 10-month-old girl presented with a 9-day history of cough, nasal congestion, and fever, with a rectal temperature as high as 38.9°C. The patient initially had been seen in the pediatric clinic for the runny nose and cough. Examination findings were reassuring at the time, so she was sent home with a diagnosis of an viral upper respiratory tract infection, and the parents were advised to offer supportive care.

The girl’s symptoms continued to worsen, and 2 days later, her mother took her to the emergency department (ED). There, the girl had a workup that included blood and urine cultures and chest radiography, the results of which were normal. She was prescribed a 5-day course of azithromycin for presumed pneumonia, given her nonremitting cough and low-grade fever.

Still, after temporary improvement, the symptoms continued to worsen, and the mother noticed increasing swelling on both sides of the girl’s neck and decreased oral intake, so the patient was brought to our clinic 6 days after the ED visit.

Physical examination findings were remarkable for the tripod position and significant drooling. Large cervical lymph nodes were palpable, with the right side greater than the left, and with pain on movement of neck. No stridor was heard, the lungs were clear to auscultation, and the patient was stable on room air. No relevant past medical, prenatal, or postnatal problems were noted.

Laboratory test results revealed a white blood cell count of 28,000/µL with 77% neutrophils and 22% bands, and a C-reactive protein level of 110.9 mg/L. Electrolytes and arterial blood gas values were normal. Due to concern for acute airway compromise, she was taken to the operating room (OR) for intubation under anesthesia to secure the airway.

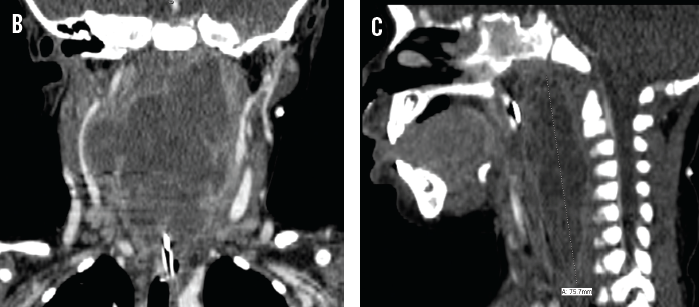

Following intubation, computed tomography (CT) revealed a large retropharyngeal abscess (RPA) measuring of 7.5 cm vertically, 7 cm laterally, and 1.8 cm anteriorly to posteriorly (A, B, and C). Associated left retropharyngeal and bilateral internal jugular adenopathy was noted. The patient was taken back to the OR for incision and drainage, and about 50 mL of green-white pus was drained from the abscess. Nasopharyngeal culture was positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Treatment was started empirically with intravenous vancomycin and ampicillin-sulbactam. The culture from the abscess grew 3+ MRSA susceptible to clindamycin and vancomycin. The patient was maintained on mechanical ventilation and intravenous antibiotics until 4 days after the incision and drainage; on the fourth day she underwent extubation, which was well tolerated. The antibiotic regimen was changed from vancomycin and ampicillin-sulbactam to clindamycin.

The girl remained afebrile during the rest of the hospital course. She was discharged home on oral clindamycin after 6 days of hospital stay. During a follow-up visit in clinic one week after discharge, she was doing well, with good oral intake.

Discussion

The retropharyngeal space is posterior to the pharynx and is bound by the buccopharyngeal fascia anteriorly, the prevertebral fascia posteriorly, and the carotid sheaths laterally. It extends superiorly to the base of the skull and inferiorly to the mediastinum.1

Acute retropharyngeal infections usually are seen in children from 2 to 4 years of age but can occur in other age groups, including neonates.2,3 While RPA is a relatively uncommon diagnosis, significant data suggest an increasing incidence, which may be attributable to better diagnostic techniques and the decreased use of antibiotics for oropharyngeal infections.4

Reports suggest the emergence of MRSA as more common pathogen than in the past, and MRSA RPA is associated with a more complicated course and increased morbidity and mortality.4,5 Community-acquired MRSA is associated with more extensive pathology than is typical group A streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, methicillin-sensitive S aureus, Klebsiella, Citrobacter, or Proteus.6-7

Patients may present at various stages of infection, with symptoms including sore throat, fever, neck stiffness, odynophagia, and cough; these variable findings pose a diagnostic problem and are a potential emergency.8-10 Because early recognition of RPA is challenging due to its relative infrequency and the lack of a subjective history, and because delays in diagnosis can lead to significant morbidity and potential mortality, pediatricians and emergency medicine physicians need to consider RPA as a possibility in patients presenting with upper respiratory symptoms with drooling and/or stridor. Children with suspected retropharyngeal infection should be hospitalized, with otorhinolaryngologist involvement. Particular attention must be paid to maintenance of the airway, with preparedness for difficult intubation.6,7

Treatment and Complications

Treatment and Complications

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated as soon as possible. Historically, ampicillin-sulbactam or clindamycin have been considered appropriate, but clindamycin or vancomycin may be more appropriate in areas with high prevalence of MRSA. Appropriate antimicrobial therapy initiated early in the disease process may prevent progression, precluding the need for surgery.

Complications of RPA include airway obstruction, septicemia, or aspiration pneumonia if the abscess ruptures into the airway. Other possible complications include internal jugular vein thrombosis, jugular vein suppurative thrombophlebitis, carotid artery rupture, and mediastinitis.

References:

1.Schwartz RH. Infections related to the upper and middle airways. In: Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:213.

2.Fleisch AF, Nolan S, Gerber J, Coffin SE. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a cause of extensive retropharyngeal abscess in two infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(12):1161-1163.

3.Lander L, Lu S, Shah RK. Pediatric retropharyngeal abscesses: a national perspective. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(12):1837-1843.

4.Wright CT, Stocks RM, Armstrong DL, Arnold SR, Gould HJ. Pediatric mediastinitis as a complication of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus retropharyngeal abscess. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134(4):408-413.

5.Elsherif AM, Park AH, Alder SC, Smith ME, Muntz HR, Grimmer F. Indicators of a more complicated clinical course for pediatric patients with retropharyngeal abscess. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(2):198-201.

6.Goldstein NA, Hammerschlag MR. Peritonsillar, retropharyngeal, and parapharyngeal abscesses. In: Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, eds. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:177-185.

7.Philpott CM, Selvadurai D, Banerjee AR. Paediatric retropharyngeal abscess. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118(12):919-926.

8.Asmar BI. Bacteriology of retropharyngeal abscess in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9(8):595-579.

9.Dawes LC, Bova R, Carter P. Retropharyngeal abscess in children. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72(6):417-420.

10.Craig FW, Schunk JE. Retropharyngeal abscess in children: clinical presentation, utility of imaging, and current management. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6 pt 1):1394-1398.