Sunscreen Sticks in Children: An Adjuvant Method of Optimal Sun Protection

ABSTRACT: Sunscreen sticks offer a method of applying adequate sun protection to children’s exposed skin. Sticks are useful for application to vulnerable and sensitive areas of the face and body, and they afford a convenient means of frequent sunscreen reapplication. Their use can make adherence to sun protection guidelines more attainable for pediatric patients in all age groups. It is important that pediatricians be versed in the basics of sun protection and published guidelines, and recommend sunscreen sticks as an effective component of protecting the skin of children from the harmful effects of solar ultraviolet radiation.

In recent years, sunscreen sticks have become a popular and widely available over-the-counter sun protection item. It is important for pediatricians to be aware of sunscreen sticks’ usefulness as a means of optimal sun protection of children’s skin.

The most recent guidelines from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommend the use of a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 15 to 50, applied to exposed areas of the body 30 minutes before sun exposure and every 2 hours thereafter.1,2 More frequent reapplication is recommended for water-based activities, since sunscreen products are labeled only as water-resistant for 40 to 80 minutes.

In addition to sunscreen recommendations, patients should be guided to avoid sun during peak hours, to seek shade, and to wear sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses. For areas of skin that are uncovered, a sunscreen stick is a relatively easy means of applying sun protection.

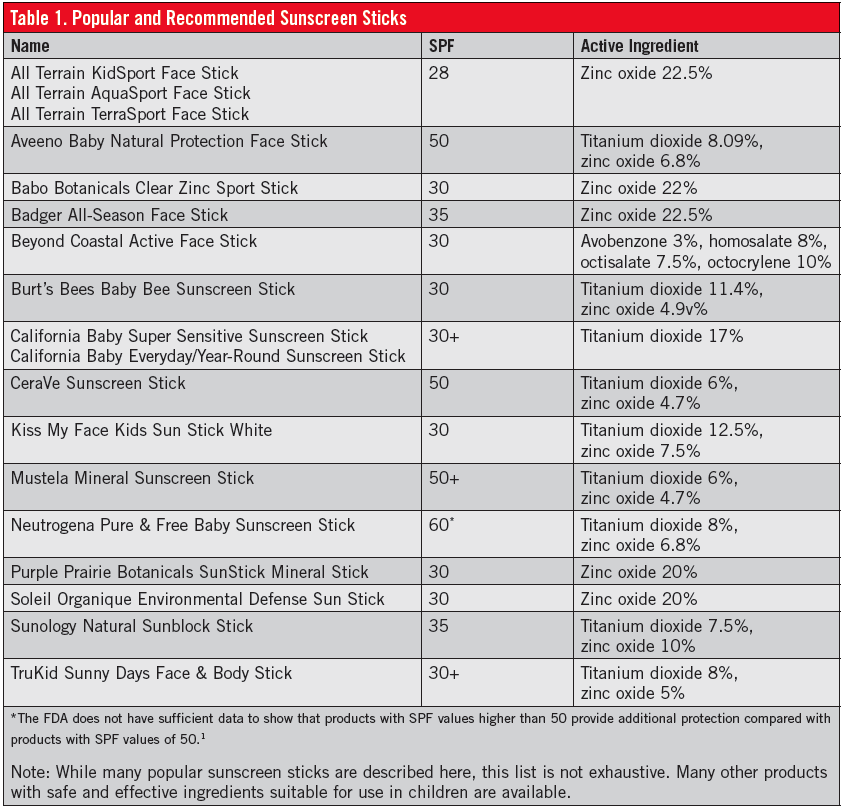

Numerous brands of sunscreen sticks are available, some of which are reviewed here, including their active ingredients and SPFs.

Children and Sun Exposure

Sun protection is of the utmost importance in the pediatric population. Ultraviolet radiation is more damaging to infants and toddlers than to older people, because young skin is thinner, has a lower concentration of melanin, and is immunologically immature.3,4 Thus, infants should avoid sun exposure when possible, and sun protection measures should be maximized for this population.

Studies have shown an increased risk of melanoma in persons with a history of sunburns during childhood.5,6 Adolescents are more likely to spend time outside as a means of intentionally tanning, and the majority of these adolescents do not use sunscreen appropriately. In one study, half of 360 Massachusetts fifth grade students experienced at least one sunburn before the of age 11 years and at least one more sunburn in the next 3 years.6 Proper sunscreen use remains an issue in children of all ages.

Sunscreen Types

Active ingredients in sunscreens that protect the skin from solar ultraviolet radiation are classified into two general categories: physical blockers and chemical absorbers.

The physical blockers, zinc oxide and titanium dioxide, physically reflect or scatter ultraviolet light and protect the skin from both UVA and UVB radiation. Chemical absorbers contain an organic compound that absorbs ultraviolet radiation and dissipates its energy as light or heat, with most products protecting the skin from UVB only.

Most sunscreen sticks on the market contain a physical blocker as their active ingredient; however, several also contain chemical absorbers. Many parents choose to avoid chemical ingredients, especially oxybenzone and vitamin A (retinyl palmitate), until more conclusive evidence becomes available regarding their safety.

However, ultraviolet light exposure is a known carcinogen, and a longstanding body of scientific evidence supports the protective benefits of sunscreen use.7

We recommend the application of sunscreen containing physical blockers to the sun-exposed skin of infants and toddlers 6 months of age or older and of children of any age with sensitive skin.

Figure. Easy application of sunscreen to sensitive areas of the face using a stick.

Sticks And Other Formulations

Sunscreen sticks are a potentially useful way of increasing adherence to optimal sun-protection methods in the pediatric population. They are particularly convenient for application to the cheeks, nose, and ears, resulting in an ample layer of sunscreen on these areas that are most vulnerable to sunburn (Figure).

Among the potential benefits of sunscreen sticks compared with other formulations is that the sunscreen in sticks tends not to run when applied to the forehead and near the eyes, which is a particularly common complaint among children when using sunscreen lotions. Sticks also are useful for the convenient reapplication of sunscreen to a child’s face and body, which is particularly beneficial when spending extended time periods outdoors.

Unlike sunscreen sprays, which also have become popular based on their reported ease of application, sunscreen sticks do not have the risk of inhalation of aerosolized chemicals. Moreover, the active ingredients in sunscreen sprays most often are chemical absorbers, as opposed to the preferred physical blockers (zinc oxide and titanium dioxide) in many sunscreen sticks.

Sunscreen sticks make it easy to apply and evenly distribute a generous layer of sunscreen; sprays, in contrast, can result in the insufficient application of sunscreen that often is unevenly distributed or unevenly rubbed into the skin. In addition, the compact size of sunscreen sticks, which generally are smaller than a glue stick or solid deodorant, makes these products convenient to carry in a pocket or a handbag.

A recent review by Osterwalder and Herzog rated adherence as the greatest challenge to optimal sun protection.8 They suggest that a lack of understanding and mixed messages in the media are factors that underlie this issue, and they note that sunscreen must be cosmetically pleasing in order for it to be applied sufficiently and frequently. Sunscreen sticks can improve compliance due to their elegance and ease of use, particularly when combined with user education and awareness.

Selecting a Sunscreen

Many brands of sunscreen sticks are available. Some are marketed specifically for use in infants and children, while others target the adult population and are labeled as “water-resistant,” “active,” or “mineral.” Many sunscreen sticks are marketed specifically for use on the face, whereas others are labeled for use on the face and body alike. Some of the most popular and effective sunscreen sticks are listed here (Table). As with any sunscreen selection, it is important that parents be advised to read sunscreen labels for the active ingredients.

Nina K. Antonov, BS, is a medical student at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, New York.

Maria C. Garzon, MD, is a pediatric dermatologist and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center in New York, New York.

Kimberly D. Morel, MD, is a pediatric dermatologist and an associate professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center.

Christine T. Lauren MD, is a pediatric dermatologist and an assistant professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center.

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1.Labeling and effectiveness testing; sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2011;76(117):35620-35665.

2.Sunscreen: the ABCs of sun protection. Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/UnderstandingOver-the-CounterMedicines/ucm239463.htm.

Accessed April 9, 2014.

3.Paller AS, Hawk JL, Honig P, et al. New insights about infant and toddler skin: implications for sun protection. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):92-102.

4Quatrano NA, Dinulos JG. Current principles of sunscreen use in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25(1):122-129.

5.Pustisek N, Sikanić-Dugić N, Hirsl-Hećej V, Domljan ML. Acute skin sun damage in children and its consequences in adults. Coll Antropol. 2010;34(suppl 2):233-237.

6.Dusza SW, Halpern AC, Satagopan JM, et al. Prospective study of sunburn and sun behavior patterns during adolescence. Pediatrics. 2012; 129(2):309-317.

7.Burnett ME, Wang SQ. Current sunscreen controversies: a critical review. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27(2):58-67.

8.Osterwalder U, Herzog B. The long way towards the ideal sunscreen—where we stand and what still needs to be done. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2010;9(4):470-481.