Three-Year-Old Boy With Excessive Drooling

HISTORY

HISTORY

Three-year-old boy with excessive drooling for 6 to 8 months. He had no difficulty in swallowing. His parents noticed that he could not move his tongue to the right, and on protruding, it deviated to the left. He had difficulty in producing certain sounds, such as f, s, sh, th, and t. At 2½ years of age, he began speech and occupational therapy to reduce drooling and improve oromotor function.

No history of visual or hearing impairment, weakness of limbs, or seizures. Child had initial mild delay in walking, but he caught up with gross motor milestones after that. He also had some fine motor coordination problems. Family history noncontributory.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Well-appearing, nondysmorphic boy, with vital signs and head circumference within normal limits. Excessive drooling noted. Oropharynx and temporomandibular joints normal. Neurological examination revealed uvular deviation to the right, normal palatal movements, intact gag reflex, and tongue deviation to the left (as shown); no atrophy or fasciculations. Motor, sensory, and cerebellar findings and gait normal.

WHAT’S YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Answer: Isolated Hypoglossal Nerve Palsy

Hypoglossal nerve palsy is a rare cause of drooling.1 This isolated palsy can be the initial manifestation of brain stem glioma. Patients with drooling should be carefully examined to detect any underlying nerve palsy.

NORMAL AND ABNORMAL DROOLING

A mild degree of drooling is normal during infancy. Drooling normally disappears by 2 years of age as a consequence of physiological maturity of oral motor function. Drooling is also a common sign of teething.

Oropharyngeal irritation, either by chemicals, drugs, and toxins or by infection, leads to increased

salivation.1 Gingivostomatitis, dental caries, tonsillar inflammation, peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis, and foreign bodies can also cause drooling. These conditions are usually acute in onset.

Esophageal obstruction and rarely gastroesophageal reflux can lead to drooling. Drooling can be caused by temporomandibular joint involvement in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Neurological disorders are another important cause of drooling.1 Drooling has been described in children with mental retardation and cerebral palsy or chorea. Myasthenia gravis, polymyositis, bulbar and pseudobulbar palsies, and facial and hypoglossal nerve palsies can also lead to drooling.

ETIOLOGY OF HYPOGLOSSAL NERVE PALSY

The hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) is a pure motor nerve that innervates intrinsic as well as extrinsic muscles of the tongue. Cranial nerve XII is usually divided into 5 segments: medullary (nuclear), cisternal (extramedullary but intracranial), skull base (passing through the hypoglossal nerve canal), nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal carotid (in close proximity to cranial nerves IX and X and the internal carotid artery), and sublingual (terminate innervating lingual muscles).2

The hypoglossal nerve can be affected by lesions located anywhere along the course. In the medullary segment, these may be caused by ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (eg, medial medullary syndrome); neoplasms, which may be primary (most often brain stem glioma, the probable cause in this patient) or secondary from metastases; demyelinating lesions (multiple sclerosis, Behcet disease, systemic lupus erythematosus); syringobulbia; poliomyelitis; botulism; and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.3

In the cisternal segment, the rootlets of the hypoglossal nerve may be susceptible to injury from compression by the vertebral artery (aneurysm or dolichoectasia) and by basal meningitis from infection or immune-mediated neuropathy from Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Direct extension of neoplasms at the skull base or fractures of the skull base may impinge on cranial nerve XII directly as it passes through the hypoglossal canal. Hypoglossal nerve injury within the carotid space and sublingual space may result from a range of disorders, of which malignant disease is the most common.4

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The clinical manifestations cranial nerve XII palsy depend on where the hypoglossal nerve is damaged.5 Damage at the supranuclear level (above the nucleus at the medulla) results in paralysis of the tongue contralateral to the lesion, and the tongue deviates away from the lesion. Our patient’s tongue deviated to the side of the lesion, which suggests damage at the nuclear or infranuclear level. Lesions at this level are typically associated with atrophy of the tongue and fasciculations,5 which were absent in this patient. In children, brain stem glioma presents most commonly with lower cranial nerve palsies.6

WORKUP

In addition to hypoglossal nerve palsy, one should look for any other neurological signs (such as cranial nerve deficits and long tract signs) that may point to the etiological diagnosis.

Neuroimaging (preferably MRI of the brain with gadolinium contrast) should be performed in all cases of suspected hypoglossal nerve injury to detect stroke, intracranial mass lesions, demyelinating lesions, and cervico-medullary junction lesions.7 When MRI findings are suspicious for a vascular anomaly, further neuroimaging studies (such as magnetic resonance angiography or conventional angiography) should be ordered to better delineate the vascular anatomy and guide the treatment plan.5 CT scan of the skull base is helpful to better characterize skull base fractures, which can lead to cranial nerve XII palsy. If the neuroimaging findings are negative, lumbar puncture that shows albuminocytological dissociation may be helpful to detect Guillain-Barré syndrome.

MANAGEMENT

MANAGEMENT

The management plan depends on the cause of the lesion. When a tumor is found, biopsy or surgical resection is necessary for definitive diagnosis.7 In the case of a brain stem glioma, surgical resection offers the greatest chance of tumor-free survival.8 However, aggressive surgery to achieve a gross total resection is not advocated because of the risks associated with this approach. Tumors that recur can be controlled with repeated resection and radiotherapy. Chemotherapy is primarily used to delay radiotherapy in young patients. Because focal gliomas tend to grow slowly, they are often managed conservatively with close observation.9 Evidence of radiographic or clinical progression should prompt referral to neurosurgery for adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy, or both.

PATIENT OUTCOME

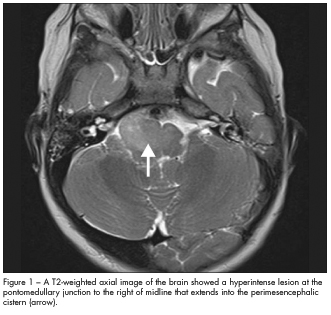

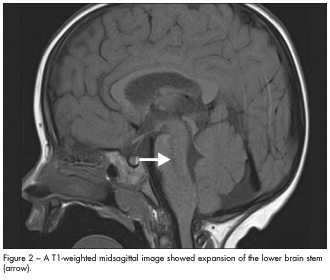

In this case, MRI scans of the brain revealed an infiltrative mass in the brain stem that involved the lower pons and medulla (Figures 1 and 2). This suggested a probable diagnosis of low-grade brain stem glioma. The child did not undergo brain biopsy for tissue diagnosis because of the critical location of the tumor. He was closely monitored by the neuro-oncology team. At follow-up 9 months later, an MRI scan showed the lesion to be stable; neurological findings were unchanged.