PATIENT PROFILE:

"Jennifer is bleeding," confides Mrs Smith outside the door to her daughter's clinic room. "She's really embarrassed to discuss it with anyone but I'm really worried. Do you think that she is having sex?" You listen to her concerns and learn that Jennifer's last menstrual period has lasted approximately 3 to 4 weeks. Jennifer and her mother came to the pediatric clinic today after Mrs Smith found multiple menstrual pads in the bathroom wastebasket every day for several days.

In the examination room, Jennifer--now 13 1/2 years old--initially seems shy about discussing this issue, but soon admits that she is really concerned. She confirms that her last period began about a month ago and that she has been bleeding daily since then. She is using about 6 or 7 menstrual pads per day and the pads are "soaked" with blood when she changes them. One day last week, she had to leave school early because the bleeding stained her clothing.

Jennifer's menstrual cycles occurred intermittently for about the first 8 months after menarche at age 12. For the past 6 months her cycles have been about one month long, with 5- to 6-day menses. She gets minimal cramping and denies any lower abdominal pain. Jennifer has been feeling light-headed for a few days and "almost passed out" this morning while she was in the shower. She occasionally feels nauseous but has not vomited.

Jennifer's mother and sister both have unremarkable menstrual histories. There is no family history of any bleeding problems or heritable diseases.

Jennifer denies any sexual contact with another person. She also denies any recent trauma to the vaginal or pelvic areas or any unusual vaginal discharge (aside from the blood, of course). She has never needed a pelvic examination or been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease.

Jennifer appears tired but is in no apparent distress. She is afebrile, but her resting heart rate is 112 beats/min with a blood pressure of 118/78 mm Hg. Her mucous membranes are moist, but the conjunctivae are pale. Examination of the HEENT, lungs, and abdomen yields normal results. The cardiac examination reveals a faint grade 1/6 systolic ejection murmur heard over the sternum.

Jennifer agrees to a limited pelvic examination, which reveals an intact hymen and a cervix with blood oozing from the os. You obtain vaginal cultures to test for gonorrheaand Chlamydia infection.

WHAT WOULD YOU DO FIRST? (please pick 2 options)

A. Check the complete blood cell (CBC) count.

B. Order a urine pregnancy test.

C. Order pelvic ultrasonography.

D. Reassure Jennifer and her mother that such bleeding usually resolves without intervention and that they should follow up with you in 1 month if the bleeding persists.

E. Order a thyroid function panel.

F. Refer the patient to hematology for coagulation studies.

THE CONSULTANT'S CHOICE

Jennifer is experiencing dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB). At this point you don't know exactly why, but your most important job is to keep her physiologically safe. The history of daily menstrual bleeding combined with complaints of dizziness and a resting heart rate of 112 beats/min suggest that Jennifer may be becoming significantly anemic. A CBC count to check her hemoglobin and hematocrit should be a priority. Results will determine whether she can be treated as an outpatient or if she needs to be hospitalized for a blood transfusion.

In addition, you need to check a urine pregnancy test to rule out the possibility of an ectopic pregnancy or a miscarriage (the intact hymen on examination does not effectively rule out sexual activity). Therefore, choices A and B are correct.

Choices C, E, and F may be reasonable options for determining the cause of DUB, but they are less important for determining immediate disease severity and treatment options. Choice D is not a reasonable consideration in this scenario. While DUB is not uncommon in adolescent girls, complaints of dizziness with an elevated pulse suggest the patient may become critically anemic if untreated.

BACK TO THE CASE . . .

Results of the urine pregnancy test are negative. The white blood cell count is 10.8/µL; hemoglobin, 9.7 g/dL; hematocrit, 29%; and platelet count, 210,000/µL. Jennifer's supine heart rate is 101 beats/min; when she stands up, however, she feels dizzy and her heart rate rises to 128 beats/min.

Given these findings, you ask yourself some fundamental questions:

1. How can I stop the bleeding and prevent anemia?

2. Does Jennifer need a blood transfusion?

3. Why did DUB develop in the first place? And once I stop the bleeding, can I keep it from returning?

While the exact incidence of DUB has not been studied, many adolescent medicine providers encounter this disorder with some frequency. The differential diagnosis for DUB is outlined below, but the great majority of cases are caused by anovulatory menstrual cycles (Box).

Most young adolescent girls have an "immature" reproductive system for the first 3 years following menarche, and they often undergo menstrual cycles in which no ovulation occurs. Without ovulation there is no corpus luteum, and without the corpus luteum no progesterone( is produced to stabilize the endometrial lining. The end result of this process is erratic and unpredictable breakdown of the endometrial wall, which leads to frequent, heavy vaginal bleeding.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

When a patient presents with symptoms consistent with DUB, quickly consider the various reasons why this may be happening. Typically, DUB is caused by 1 of 3 things: infection, bleeding diatheses, or hormones.

• Infection: Always consider the possibility that the patient may be sexually active (either consensually or against her will). The status of the hymen does not effectively provide any information about past coital activity. Gonorrhea and Chlamydia infections (as well as other sexually transmitted infections) can advance up the female reproductive tract and can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) with infection and inflammation of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries.

PID typically presents with lower abdominal pain, but it can easily present as atypical vaginal bleeding. For this reason, it is important to obtain cervical cultures--or at least vaginal cultures for gonorrhea and Chlamydia. A sedimentation rate will also provide nonspecific information about the presence of inflammation.

• Coagulation disorders: Most bleeding disorders present relatively early in a patient's life. However, it is possible for females to have von Willebrand disease without knowing it until they present with heavy or uncontrolled menses. DUB caused by such a process typically presents with heavy menses from the time of menarche.

Less commonly, affected patients present with coagulation disorders later in their menstrual life. Entities such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, platelet dysfunction (secondary to NSAIDs), or coagulopathy from systemic illness (eg, liver disease) may present with menorrhagia at any time after menarche.

• Hormones: As noted, an immature, anovulatory menstrual cycle is frequently implicated as a cause of DUB--especially in younger adolescent girls. As in Jennifer's case, pregnancy must be ruled out because of the risk of an ectopic implantation or a miscarriage. Other causes of menorrhagia include polycystic ovarian syndrome (presenting with obesity, hirsutism, and acne) and hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism. Excessive exercise can also lead to anovulation and subsequent DUB. Finally, endometriosis has been shown to be present in about 1 in 10 adolescents with persistent vaginal bleeding.

• Other, less common causes of DUB can include retained tampons or other foreign bodies in the vagina, vaginal trauma, and neoplastic processes. The use of medroxyprogesterone( acetate (Depo-Provera, an injection) or low-dose oral contraceptive pills can also cause mild DUB, especially when therapy is first begun.

BACK TO THE CASE . . .

Treatment options for Jennifer are the next thing to consider. She is not pregnant or thrombocytopenic, but she does have moderate anemia with orthostasis. It would be wise to take measures to prevent any exacerbation of these entities, even before any other laboratory results are available.

WHAT WOULD YOU DO NOW?

A. Prescribe a multivitamin with iron and have the patient follow up with you in 3 days.

B. Admit the patient to the hospital and initiate therapy with a high-dose combination oral contraceptive pill.

C. Refer to gynecology for dilatation and curettage.

D. Refer to hematology for coagulopathy workup.

E. Refer to the emergency room and initiate an immediate blood transfusion.

Once admitted to the hospital, Jennifer can receive a medium-dose monophasic oral contraceptive pill, such as Lo/Ovral (ethinyl estradiol(/norgestrel), every 6 hours for 2 days or until the bleeding stops.

Once the bleeding is controlled, the dose can be reduced by 1 pill/d for the next 3 days until the patient is taking the normal dose of 1 pill/d. Remember that high-dose estrogen can cause significant nausea. I give antiemetics for comfort.

Dilatation and curettage should only be considered if both oral and intravenous estrogen therapies have failed to stop the vaginal bleeding. While a coagulation workup should be part of any DUB evaluation, the immediate goal is to stop the bleeding and ultimately stabilize the patient.

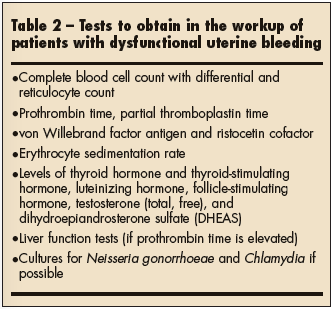

Once you have determined that the patient is stable, the next step is to determine what caused the DUB. Table 2 lists laboratory tests that can provide answers. Keep in mind that the presence of exogenous estrogen can occasionally affect the results of some of the tests involving hormones or coagulation. Therefore, if the patient is stable enough, it is preferable to perform these tests before you start hormonal therapy.

Once you have determined that the patient is stable, the next step is to determine what caused the DUB. Table 2 lists laboratory tests that can provide answers. Keep in mind that the presence of exogenous estrogen can occasionally affect the results of some of the tests involving hormones or coagulation. Therefore, if the patient is stable enough, it is preferable to perform these tests before you start hormonal therapy.

While it is important to consider the broad differential diagnosis in DUB, the majority of cases are simply the result of an immature ovulatory process. Once the bleeding has stopped, most girls may take a once-a-day oral contraceptive for about 4 to 6 months--after which time they can try to discontinue the hormones. At this point, ovulation usually occurs and DUB becomes less of a concern.

Follow-up is in order every few weeks after the initial presentation to ensure that the anemia is resolving and that the patient is asymptomatic. Remember to counsel these adolescents about the potential for pathologic blood clots (such as a deep venous thrombosis) if there is a family history for this type of phenomena or if the patient is a smoker. If the adolescent has these risks for venous thrombosis, then treatment should be discontinued at the earliest possible time.