What’s Causing This Boy’s Dyspnea, Vomiting, and Weight Loss?

A 6-year-old boy with poorly controlled asthma presented with difficulty breathing, persistent vomiting, and a 7-pound weight loss. Initial chest radiographs showed nonspecific bilateral lower-lobe infiltrates. Despite intravenous antibiotic administration and aggressive asthma management, his symptoms persisted.

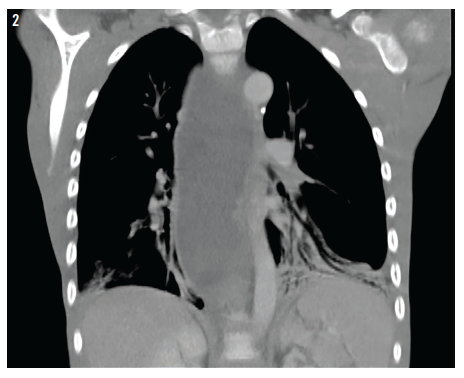

On further evaluation, further chest radiographs were ordered (Figure 1), along with computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest (Figure 2).

What do these images suggest is causing the boy’s symptoms?

A. Gastroesophageal reflux

B. Achalasia

C. Esophageal carcinoma

D. Eosinophilic esophagitis

(Answer and discussion on next page)

Answer:

B, achalasia

On further evaluation, the chest radiograph showed what appeared to be a dilated and fluid-filled structure in the boy’s mediastinum (Figure 1). The CT of the chest showed bilateral lower-lobe infiltrates, along with the unexpected finding of a severely dilated, fluid-filled esophagus (Figure 2), which correlated with chest radiography findings. This raised suspicion for achalasia.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy subsequently demonstrated a dilated, fluid-filled esophagus with normal mucosa and a hypertonic lower esophageal sphincter (LES). High-resolution esophageal manometry confirmed the diagnosis of achalasia.

Discussion

Achalasia is a disorder of esophageal motility in which a lack of or loss of local inhibitory ganglion cells impedes nerve impulses to the LES, resulting in diminished or absent esophageal peristalsis and impaired relaxation of the esophagus during swallowing.

The most common presenting symptoms of achalasia are vomiting, dysphagia, and weight loss. However, as many as half of patients with achalasia present with significant respiratory symptoms. The mean age at diagnosis in children is 11 years, with an incidence of approximately 0.1 to 0.3 cases per 100,000 children per year.1,2

Delays in diagnosis often are due to achalasia’s insidious onset, symptomatic overlap with reflux and asthma, and a lack of specific complaints of dysphagia. The diagnosis is suggested by the characteristic findings on barium esophagogram of a dilated esophagus tapering to a bird’s beak at the LES, although findings can be nonspecific early in the course of achalasia. Esophageal manometry is the most sensitive and specific diagnostic tool, and it shows aperistalsis of the esophageal body with partial or complete lack of LES relaxation.1

Left untreated, achalasia is a progressive condition that can result in severe malnutrition. Definitive repair is with a Heller myotomy, in which the LES muscles are cut; it usually is performed along with partial fundoplication to prevent severe reflux. Pneumatic dilation of the LES also is a treatment option, but it may require repeated dilations. While smooth-muscle relaxants and botulinum toxin injections of the LES may be palliative, they are not viable long-term treatment options.3

Although uncommon, achalasia should be considered in cases of respiratory symptoms that do not respond to conventional therapies, particularly in the setting of dysphagia, weight loss, or recurrent vomiting.

Sumreen Hussain, MD, is in the Department of General Pediatrics at Levine Children’s Hospital in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Jason Dranove, MD, is in the Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at Levine Children’s Hospital in Charlotte, North Carolina.

William Yaakob, MD—Series Editor, is a radiologist in Tallahassee, Florida.

References

1. Ambartsumyan L, Rodriguez L. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in children. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2014;10(1):16-26.

2. Sood MR, Rudolph CD. Achalasia. In: Liacouras CA, Piccoli DA, eds. Pediatric Gastroenterology: The Requisites in Pediatrics. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:13-18.

3. Franklin AL, Petrosyan M, Kane TD. Childhood achalasia: a comprehensive review of disease, diagnosis and therapeutic management. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6(4):105-111.