What’s Causing This Boy’s Hair Loss?

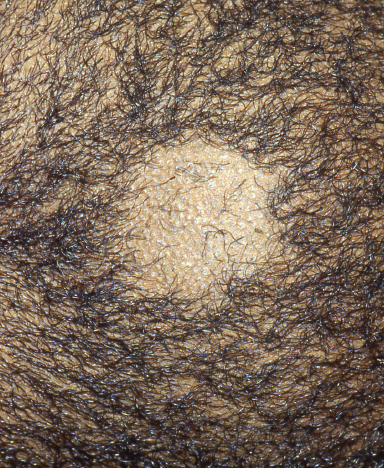

A 6-year-old African American boy was seen in clinic with a patch of hair loss of approximately 2 cm in diameter.

The patient had developed a small erythematous papule on his scalp 3 weeks before presentation that developed into a larger pruritic patch containing brittle, broken hairs.

The area was scaly but had no signs of inflammation. The patient had no other areas of hair loss.

Can you identify the cause of this boy’s hair loss?

(Answer and discussion on next page)

Answer: Tinea capitis

Following microscopic examination and culture of the patient’s hair, a diagnosis of tinea capitis was made. Tinea capitis is the most common dermatophyte infection in the pediatric population,1 with a peak incidence in school-aged children between 3 and 7 years of age. The overall incidence of this dermatophyte is increasing in the United States and has been estimated at approximately 4%, with higher rates in the African American population.2

The infection is caused by 3 main genera of fungi: Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton. Trichophyton tonsurans has been shown to be responsible for more than 90% of cases of tinea capitis in the United States.3 Tinea capitis usually is spread by direct person-to-person contact or through fomites, although several zoophilic species have been known to infect humans.

The clinical presentation of tinea capitis can vary significantly, from mild pruritus with minimal hair loss to severely inflamed and abscessed kerion formation. Proper diagnosis of kerions is important, because scarring with permanent alopecia can result. Other potential complications include painful cervical lymphadenopathy and id reactions.

Diagnosis of some tinea capitis infections may be assisted by visualization with a Wood lamp, which causes Microsporum species to fluoresce a bright yellow. Trichophyton species, however, do not exhibit fluorescence with the Wood lamp. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed by obtaining a sample of hair for microscopy and culture. Moistened gauze can be used to obtain samples from young children, who may be traumatized by the plucking of hairs or by the use of a scalpel blade.4,5 The gauze is rubbed on the scalp, and broken hairs can be examined under the microscope using potassium hydroxide to identify hyphae in the hair shaft. Culture is recommended to allow for species identification,6 but this may take 2 weeks or longer.

Systemic therapy is required for the treatment of tinea capitis, since topical antifungals do not effectively penetrate the hair shafts to eradicate the dermatophyte infection. Griseofulvin for 6 to 8 weeks remains the standard medication for the treatment of tinea capitis.7 Griseofulvin should be taken with foods with some fat content to improve the medication’s absorption. Other antifungals—including terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole—also are used and have the added benefit of a shorter duration of treatment.8

As an adjunct therapy, 1% or 2.5% selenium sulfide or 2% ketoconazole shampoo may improve treatment and reduce transmission. Oral antihistamines can be used in patients with severe pruritus, and systemic corticosteroid therapy may be required for the treatment of kerion. It has also been recommended that family members use selenium sulfide or ketoconazole shampoo for several weeks, because studies have shown that up to 50% of children with tinea capitis have at least one culture-positive but asymptomatic family member.9

Our patient was treated for 8 weeks with griseofulvin, with complete resolution of the infection and no scarring at approximately 6 weeks.

References:

1.Gupta AK, Hofstader SL, Adam P, Summerbell RC. Tinea capitis: an overview with emphasis on management. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16(3):171-189.

2.Sharma V, Hall JC, Knapp JF, Sarai S, Galloway D, Babel DE. Scalp colonization by Trichophyton tonsurans in an urban pediatric clinic: asymptomatic carrier state. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(10):1511-1513.

3.Roberts BJ, Friedlander SF. Tinea capitis: a treatment update. Pediatr Ann. 2005;34(3):191-200.

4.Hubbard TW, de Triquet JM. Brush-culture method for diagnosing tinea capitis. Pediatrics. 1992;90(3):416-418.

5.Friedlander SF, Pickering B, Cunningham BB, Gibbs NF, Eichenfield LF. Use of the cotton swab method in diagnosing tinea capitis. Pediatrics. 1999;104(2 pt 1):276-279.

6.Ali S. Graham TA. Forgie SE. The assessment and management of tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23(9):662-665.

7.Gupta AK. Ryder JE. Nicol K. Cooper EA. Superficial fungal infections: an update on pityriasis versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis, tinea capitis, and onychomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21(5):417-425.

8.Chan YC. Friedlander SF. New treatments for tinea capitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17(2):97-103.

9.Frieden IJ. Tinea capitis: asymptomatic carriage of infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(2):186-190.

Dr Johansen is a dermatologist in Tampa, Florida.

Kirk Barber, MD, FRCPC––Series Editor:Dr Barber is a consultant dermatologist at Alberta Children’s Hospital and clinical associate professor of medicine and community health sciences at the University of Calgary in Alberta.