Working with Interpreters in Psychotherapy: A Case Report Using the Therapist-Interpreter Team Approach

Introduction

In 2005, On Lok Senior Health Services, a comprehensive long-term care health plan for the frail elderly, took on the challenge of offering in-house mental health services for its senior population.1 The On Lok Lifeways mental health team faced the complex task of providing quality mental healthcare to an extremely diverse population. To illustrate the enormity of this challenge: On Lok serves more than 1100 elderly persons who speak over 30 different languages. Cultural and linguistic diversity render it nearly impossible to offer mental health services to patients in their native languages. Therefore, reliance on interpreters became essential to provide care.

Like other healthcare providers facing these challenges, On Lok teams frequently have had to turn to telephone translation services to meet the diverse linguistic needs of its population. In recent years, telephone translation services have become a more developed field, with guidelines now published for medical telephone interpreting.2,3 However, in the field of mental health, telephone interpreting cannot substitute for face-to-face translation.4 With telephone interpreting, there is too great a risk for interpreter errors and too much potential damage to the therapeutic alliance, with fewer possibilities for correction and repair.

The use of on-site interpreters also presents challenges. The majority of interpreters are not specifically trained to work in mental health settings, just as the majority of psychotherapists are not trained to work with interpreters. The vicissitudes of psychological communication within the therapy framework yield a complex interplay of cognition, emotion, and nonverbal expression. Interpreter errors can be frequent, and misunderstandings often arise. The consequences of miscommunication are profound: the potential for misdiagnosis and ineffective treatment.5-7

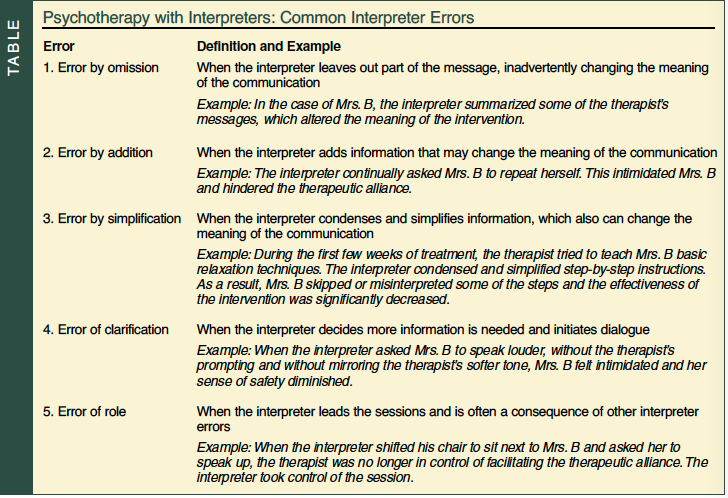

The following case illustration demonstrates how common interpreter errors can interfere with treatment. The therapist-interpreter team approach is then discussed as a possible method to minimize errors and promote effective treatment.

Case Presentation

Mrs. B was a 76-year-old monolingual Spanish-speaking, Mexican-American woman. Reportedly, she had suffered from years of spousal abuse by her now deceased alcoholic husband. Mrs. B also had multiple medical problems including congestive heart failure, arthritis, diabetes, difficulty hearing, and mild secondary parkinsonism with muted facial expressions, tremors, stiffness, and soft speech. A widow for 10 years, Mrs. B was the mother of 15 children, had no formal education, and lived with one unmarried son.

Mrs. B had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder, and was treated with antidepressants for over 6 months with very little success. Her symptoms included nightmares, insomnia, anhedonia, and social anxiety. Her primary care physician referred Mrs. B for psychotherapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety.

During her initial assessment, Mrs. B was withdrawn and soft-spoken. She appeared distressed and uncomfortable, her facial expressions sullen and body language tense. A professional interpreter who focused on making factual translations was used during the interview. Mrs. B, with her parkinsonism symptoms and her difficulty hearing, was very hard to understand. Following the best practice guidelines of his profession, the interpreter focused on accuracy, seeking frequent clarification from Mrs. B when he failed to understand her. By asking her to speak up or to slow down, the interpreter inadvertently took control of the pace of the session. Furthermore, he tried to maintain his professional standard of impartiality by showing little emotion.8 Mrs. B responded to questions minimally, became increasingly withdrawn, and appeared intimidated by the clinical setting.

Over the next several sessions, Mrs. B failed to establish a therapeutic alliance with the psychotherapist. In fact, the more the therapist and interpreter tried to engage with Mrs. B, the more soft-spoken and withdrawn she became. The more withdrawn she became, the more the interpreter intervened. By seeking clarification, the interpreter was inadvertently making an intervention, which disrupted the development of the therapeutic alliance. Not surprisingly, Mrs. B’s anxiety and depression symptoms were not alleviated. In fact, the symptoms were getting worse. She continued to have nightmares, insomnia, anhedonia, and social anxiety. After a few sessions, it became apparent that Mrs. B was not feeling safe and secure within the therapeutic environment. Though competent and professionally trained, the interpreter did not have an adequate understanding of the unique communication demands of the mental health settings. The inclusion of the interpreter in the sessions was creating a barrier to establishing a therapeutic alliance.

To respond to these challenges, the psychotherapist initiated a therapist-interpreter team approach. This approach acknowledges the interpreter’s impact on the therapeutic relationship, and uses education and modeling to reduce interpreter errors and to teach interpreters how to work in a mental health setting. Once a team approach was implemented, interpreter errors were greatly reduced, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques were used successfully to alleviate the patient’s symptoms.9,10

Discussion

The case involving Mrs. B demonstrates the difficulties of building a therapeutic rapport when an interpreter is present in the session. When an interpreter initiates contact, even for the purposes of furthering his or her understanding, the therapist is at risk of losing control of the session. The Table illustrates common interpreter errors that can interfere with accurate assessment and effective treatment. In the case of Mrs. B, the professionally trained interpreter strived to be factually accurate, and errors by addition and errors of clarification were especially frequent and disruptive. In fact, by frequent intrusions he was triggering Mrs. B’s PTSD symptoms. More problems arose in the development of a therapeutic alliance when this interpreter’s impartial, detached demeanor was experienced as “cold” and alienating to Mrs. B, who had a long history of domestic abuse. Clearly, Mrs. B was not feeling trust or safety within the therapeutic environment.

Many interpreters are trained to be neutral, an invisible presence with negligible influence. However, during sessions with Mrs. B, it became clear that the interpreter was neither neutral nor invisible. He was most definitely having an influence, just the wrong kind. In turn, the therapist was losing her ability to influence and direct the course of treatment. In summary, the impact of the interpreter was a weakened therapeutic alliance, less patient disclosure, and no change in PTSD symptoms.

It became clear that for effective treatment, the interpreter’s impact on the clinical frame needed to be acknowledged and that a method of dealing with the interpreter’s impact should have been incorporated into the therapy process. Using an interactive model, a therapist-interpreter team approach was implemented in which the interpreter’s presence and therapeutic impact were included in the treatment process.11,12 The foundation of the therapist-interpreter team approach is the collaborative relationship between the therapist and interpreter. The importance of developing trust between a clinician and an interpreter should not be underestimated.13 An alliance between therapist and interpreter can be cultivated through regular meetings, during which the interpreter’s role and impact are continually clarified and redefined. This model necessitates training interpreters to work in mental health settings.

In the case of Mrs. B, the interpreter was educated on the basic clinical tools of psychotherapy, including the importance of mirroring the therapist’s tone, and even body language. This proved to be an important step in translating therapeutic empathy, which helped Mrs. B to feel safe and understood. Common interpreter errors, as indicated in the Table, were explained and reviewed. In addition, as the interpreter began to mirror the therapist’s empathy for Mrs. B, he also began to experience a connection with her. As he became more attuned to her traumatic story, the sessions had more of an impact on him. Meeting with the therapist after sessions enabled the interpreter to process his emotional reactions, which proved to be an important part of helping him stay focused and engaged in sessions. This further strengthened the therapist-interpreter team.

Another important aspect of the therapist-interpreter team was the interpreter’s role as cultural liaison.14-16 Because literal translation can convey the wrong meaning, an interpreter is often left in the position of interpreting the cultural context of patients’ messages. The interpreter in the case of Mrs. B was not only bilingual, but he was also bicultural. Meeting with the interpreter regularly before and after sessions gave the therapist an opportunity to both learn from the interpreter as well as give him feedback. The interpreter was able to act as a cultural consultant to the therapist, while the therapist was able to educate the interpreter on effective communication styles within the clinical setting. In short, the therapist-interpreter team approach is designed to ensure that multilingual and multidimensional communications are interpreted accurately, and that the therapist can maintain control of the therapy process.

In the case of Mrs. B, once the therapist-interpreter team was formed, the shift in the therapeutic alliance was marked. For example, when Mrs. B spoke softly and the therapist responded to her gently, the interpreter translated with equal gentleness. Thought was given to the seating arrangements in sessions. Chairs were positioned in a triangle formation, with the patient sitting directly across from the therapist. This enabled the therapist to maintain eye contact throughout the session, enhancing and reinforcing attachment to the therapist. Mrs. B began to develop trust and to share her story. In combination with antidepressant medication, CBT was used effectively to reduce PTSD symptoms.17 For the first time in 10 years, Mrs. B was sleeping soundly, not plagued by nightmares or flashbacks, and was free of depressive symptoms.

In conclusion, the team approach to working with an interpreter allowed the therapist to maintain control of the therapy process and implement her treatment plan. Educating the interpreter on basic clinical principles facilitated empathy and the formation of a strong therapeutic alliance. Taking the time to review common interpreter errors helped minimize the negative influence that the interpreter was having on the treatment process. Regular team meetings reinforced clear communication and supported the therapist in carrying out an effective treatment plan. Although time-consuming at the beginning, this therapist-interpreter team approach proved to be very effective for the long term.

As our society grows increasingly diverse, we must learn to face the challenges of providing services to persons of many different cultures who speak many different languages. Cross-cultural counseling, which may necessitate using an interpreter, presents many challenges that can render therapy ineffective. Patients can easily be misunderstood, thus generating misdiagnoses and weak therapeutic alliances. Without proper training, interpreters may struggle with accurately translating therapists’ communication, which then contaminates sessions and usurps therapists’ control of the treatment process.

The team approach to using an interpreter in mental health settings supports a collaborative relationship between therapist and patient. In the case of Mrs. B, this collaborative relationship enabled therapy to proceed smoothly and effectively. The interpreter’s role as cultural liaison also helped minimize misunderstanding. Mrs. B was left feeling safe and supported, the therapeutic relationship was strengthened, and specific CBT treatment techniques were conveyed accurately and effectively. The therapist-interpreter team approach has provided the On Lok Lifeways mental health team with a framework in which to manage the clinical complexities of working with interpreters while better serving its diverse population.

Outcome of the Case Patient

Therapy with Mrs. B was able to proceed effectively once the therapist-interpreter team approach was implemented. Mrs. B’s PTSD symptoms were mostly resolved within 9 months of onset of treatment. Two years after the initial treatment, Mrs. B fractured her hip and was hospitalized. The hospital environment triggered an escalation of her anxiety and left her vulnerable to a recurrence of PTSD symptoms. The therapist, along with the same interpreter, met with Mrs. B in the hospital and skilled nursing facility. Although considerable time had passed since Mrs. B’s initial treatment, the therapeutic alliance had held; the therapist was able to provide Mrs. B with support and to reinforce the CBT tools Mrs. B had learned in earlier sessions. Mrs. B still has occasional bouts of anxiety; however, she remains free of PTSD symptoms.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgment An abstract of this study was presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, March 2008. Ms. Dekker is a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and Mental Health Clinician, and Dr. Ginsburg is a Clinical Psychologist and Director of Mental and Behavioral Health Services, On Lok Lifeways, San Francisco, CA. Dr. Lantz is Chief of Geriatric Psychiatry, Beth Israel Medical Center, First Ave @ 16th Street #6K40, New York, NY 10003; (212) 420-2457; fax: (212) 844-7659; e-mail: mlantz@chpnet.org.