What Next When Your Patient Doesn’t Respond to Therapy?

ABSTRACT: There are a number of options to consider in patients with difficult to control asthma. Education can help improve compliance with inhaled corticosteroid therapy or correct faulty metered-dose inhaler (MDI) technique. Options for patients with poor MDI technique include use of a spacer or an alternative device, such as a nebulizer or a dry powder inhaler. If therapy is ineffective, consider alternative conditions that mimic asthma, especially vocal cord dysfunction and upper airway obstruction. Treatment of comorbid conditions, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease or rhinosinusitis, may improve control. In refractory asthma, it is crucial to identify allergic triggers and reduce exposure to allergens. If another medication needs to be added to the inhaled corticosteroid, consider a long-acting betaagonist, leukotriene modifier, or the recombinant monoclonal anti-IgE antibody omalizumab.

A 23-year-old woman’s asthma symptoms have worsened during the past year. Specifically, she notes increased wheezing during the day and more nighttime attacks that wake her up. She has been using her inhaler several times each day and almost every night. During the past year, she has been hospitalized twice because of her asthma; in the past month, she has made 3 unscheduled office visits and 1 emergency department (ED) visit. This woman’s case exemplifies the fact that asthma cases are on the rise. Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that affects 24.6 million persons in United States.1 An estimated 10.6 million asthmarelated visits were made to physician offices, in addition to the 1.6 million ED visits in 2006 alone.2,3 Asthmarelated costs and expenditure amount to more than $30 billion each year.4 Asthma continues to be a significant burden on the medical infrastructure, in spite of ardent measures taken by the different organizations. In this article, we will discuss options to consider in a patient with difficult to control asthma.

ASTHMA MIMICS

Keep in mind that “all that wheezes is not asthma” (Table 1). When asthma does not respond to traditional therapy, it may be because the patient has another syndrome that mimics asthma, or because he or she has a comorbid condition that complicates it (Box I). The 2 most common syndromes that mimic asthma are vocal cord dysfunction and upper airway obstruction. Both may result in dyspnea and apparent wheezing, yet show little or no response to standard asthma therapy. Vocal cord dysfunction. Also called “factitious asthma,” vocal cord dysfunction causes recurrent, severe shortness of breath, and inspiratory stridor that is easily confused with wheezing. The condition typically occurs in women between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Keep in mind that concomitant asthma may be present. Patients often present in respiratory distress, and inspiratory stridor is the principal finding on physical examination, although this is often mistaken for wheezing. Arterial blood gas levels are usually normal, but there may be alveolar hypoventilation with increased carbon dioxide concentration.

Results of pulmonary function tests are also usually normal, although they may demonstrate a flattened inspiratory loop that is consistent with extrathoracic obstruction. The condition is often associated with psychological problems; many patients have depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder. The physiologic basis is the paradoxical adduction of the vocal cords on inspiration (they normally abduct during both phases of the respiratory cycle). The diagnosis is thus confirmed by direct visualization of the cords. A bronchoprovocation test may also help rule out true reactive airway disease. Treatment of vocal cord dysfunction is difficult, although speech therapy to teach the patient to relax the throat muscles may help. The role of psychiatric therapy is controversial.

Upper airway obstruction. Although less common, this can have the same presentation as vocal cord dysfunction and is also frequently misdiagnosed as asthma. Possible causes of upper airway obstruction include benign or malignant neoplasm, increased soft palate tissue, tonsillar hypertrophy, foreign-body aspiration, goiter, and tracheal stenosis. As with vocal cord dysfunction, diagnosis of upper airway obstruction usually requires direct visualization of the oropharynx, either through physical examination or by bronchoscopy. Other mimics. Other conditions that may be confused with asthma include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchitis, congestive heart failure, bronchiectasis, and recurrent aspiration. Each of these requires specific therapy and may need to be ruled out if an “asthmatic” patient fails to respond to standard asthma medications.

A considerable portion of the newest guidelines (National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3 [EPR-3]) is devoted to defining and helping clinicians understand the concept of asthma control.5 Simply, asthma control is the level of control patients achieve while they are receiving their current therapy. It refers to current symptoms (eg, need for use of beta-agonists, nighttime awakenings) and future risk of exacerbations. The guidelines recommend the use of simple patient questionnaires, which can be easily scored to determine asthma control. If asthma is not well controlled, therapy needs to be stepped up to achieve better control. One simple test, the Asthma Control Test, can be accessed online or at www.asthmacontrol.com.

HURDLES IN ACHIEVING OPTIMAL CONTROL

Good asthma control entails occurrence of daytime symptoms not more than twice per week, nighttime symptoms not more than twice per month, use of rescue inhalers no more than twice per week, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) or peak flow levels higher than 80% of the predicted or personal best, and no more than 1 exacerbation during the previous year.5 It has been noted through different surveys that both patients and physicians underestimate the severity of symptoms or overestimate the patient’s level of disease control.6

Asthma education. Asthma self-management education, with specific plans for daily management and recognizing and handling worsening disease, is associated with favorable outcomes in persons with chronic asthma.5 Patient education decreases asthma-related hospitalization and improves daily function. 5,7,8 Encourage patients and family members to be active partners in the management of the disease. This can be achieved by identifying concerns and preferences regarding treatment, developing treatment goals, and encouraging active selfassessment and self-management of asthma.

Inhaler technique. Improper use of the device limits the effectiveness of the medication delivered and results in considerable disruption to the daily life of an asthmatic patient. Three different basic inhalers are available on market now: metereddose inhalers (MDIs), dry powder inhaler (DPIs), and nebulizers. Poor inhaler technique can markedly reduce the proportion of drug that reaches the lung and, thus, result in inadequate treatment—which both patient and physician may mistake for failure to respond. When a patient uses an MDI, the inhalation should be slow, whereas with a DPI, it should be as deep and hard as possible.9 Metered-dose inhalers. Poor coordination, which is especially common among those who are ver y young or very old, is one of the most frequent mistakes patients make when using an MDI and it significantly reduces lung deposition.9 Patients often inhale too fast when using an MDI. Stopping inhalation at the time of actuation is another common mistake. Educational and motivational programs aimed at teaching the proper inhaler technique should be instituted at each visit (Box II).

After instruction, observe the patient’s technique. Choosing a device preferred by the patient on the basis of ease or comfort is also helpful. Spacers. An alternative in patients with poor technique is to use a spacer or a holding chamber. It decreases drug deposition in the oropharynx by facilitating delivery, reducing local adverse effects, and improving lung deposition. To use the spacer, the patient discharges the MDI into the chamber and within 3 to 5 seconds begins to inhale slowly. It still requires some coordination, and it can decrease the output of an MDI because of deposition and static electricity in the chamber. Most commercially available spacers seem to offer similar results, and they can certainly improve deposition in patients with poor technique.10 However, spacers may also reduce compliance, since these bulky devices are inconvenient to carry. Many insurance companies will not pay for the device, and they can be difficult to clean. Dry powder inhalers. DPIs improve delivery for patients who are unable to use an MDI properly. Their drug delivery has been shown to be equivalent to or slightly better than that of MDIs. The patient’s inhalation flow interacts with the resistance inside the DPI to generate a turbulent flow, which releases the formulation. Patients must perform a rapid inhalation of 1 to 2 seconds. If this does not occur, the emitted particles are too large and are deposited in the oropharynx. Another problem with DPIs is reduced effectiveness during periods of severe wheezing and in patients with low pulmonary function, because the devices are effort dependent.

Nebulizers. Yet another option is aerosolized delivery via a nebulizer. Although the drug delivery of a nebulizer is equivalent to that of a properly used MDI, a nebulizer may provide better delivery for patients who are unable to learn other methods. However, these devices can be bulky and expensive, and many newer controller medications are not available by this route.

Noncompliance. One of the main reasons for uncontrolled asthma is noncompliance with medication. Poor compliance can result from inadequate understanding of the disease and treatment, fear of adverse effects, and insufficient communication between the patient and physician. In one survey, 87% of physicians believed that their patients stopped controller medications without their advice. Inhaled corticosteroids are associated with the poorest rates of compliance.11 In another survey, at least 50% of patients refused to use higher inhaled corticosteroid doses prescribed for regaining asthma control.12 There are no easy shortcuts to take to improve patient adherence to medication regimens. Take time to teach patients about the disease, its pathogenesis, and its triggers. Frequent follow-up visits are an ideal way to provide time for education, to assess compliance, and to remind patients to continue appropriate therapy. Have written action plans for the management of exacerbations. Make sure patients understand the importance of maintenance therapy despite lack of symptoms; in particular, stress the need to use inhaled corticosteroids regularly.

Allergen exposure. A number of allergic triggers clearly influence asthma severity (Table 2).

Finally, be alert for irritants, such as air pollution, fumes, smoke, and sprays. Common sources include per fumes; cigarettes; cleaning agents; and indoor stoves, fireplaces, or heaters that lack proper ventilation. Affected patients will benefit from immunotherapy, which is discussed below.

COMORBID CONDITIONS

There are several co-existent diseases that might cause worsening of asthma control. Conditions that complicate the diagnosis of asthma are gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), chronic sinusitis/rhinitis, obesity, chronic stress/depression, and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA).

Gastroesophageal reflux disease. GERD is increasingly recognized as a trigger for asthma exacerbations. The exact nature of the interaction is not yet understood. Hypotheses include micro-aspiration of acid, which causes bronchospasm, or a reflex action in which refluxed acid causes an increase in vagal tone that in turn results in increased airway resistance. Consider GERD in any patient whose asthma worsens at night, when reflux is more likely to occur. Medical management with a proton pump inhibitor often ameliorates asthma symptoms.14 In addition to drug therapy, lifestyle modifications— weight loss, low-fat diet, avoiding food before going to bed, and sleeping with the head of the bed elevated—can be beneficial. In patients with asthma who are receiving GERD therapy, monitor the clinical response and measure peak flow. If there is no evidence of improvement, change or discontinue antireflux therapy. If there is any question about the diagnosis or treatment of GERD in such patients, consider referral to a gastroenterologist.

Obstructive sleep apnea. A high prevalence of OSA has been reported in patients who have unstable asthma.15 Patients with concurrent OSA and asthma have worsened nighttime symptoms. This can be attributed to dual mechanisms: hypoxemia during obstructive apnea episodes may predispose to increased bronchial reactivity5 and sleep disruption secondary to nocturnal asthma results in periodic breathing with decreased upper airway muscle activity, contributing to upper airway obstruction. Therefore, patients with difficult to control asthma and a higher likelihood of OSA should undergo screening nocturnal sleep oximetry. Rhinitis/sinusitis. Whether related to an allergic or infectiouscause, these disorders are often under- recognized as causes of asthmatic flares. Since upper and lower respiratory tract mucosal properties are identical and exist in continuity, rhinitis and sinusitis have been shown to induce inflammatory markers in the bronchial epithelium.16 Treat asthmatic patients who have co-existing rhinitis or sinusitis with nasal corticosteroid preparations or antibiotics as indicated.

Obesity. Improvement in FEV1, reduction in exacerbations, and improved quality of life were noted in obese asthmatic patients following weight loss.17 EPR-3 guidelines suggest that physicians encourage weight loss in obese and overweight asthmatic patients.5

Psychosocial factors. Stress and depression can precipitate asthma.5 Inquire about possible stressors in patients with difficult to control asthma at every office visit.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Suspect ABPA in patients with asthma, recurrent cough, and pulmonary infiltrates on a chest radiograph. Patients with ABPA will have a positive skin test to Aspergillus species, elevated total serum IgE level, and central bronchiectasis on a chest CT scan. Treatment consists of oral corticosteroids and antifungal agents (eg, itraconazole).

Drug-induced asthma. At least 30% of patients with asthma may have a sensitivity to aspirin. Samter’s triad, or “triad asthma,” is a syndrome that involves aspirin sensitivity, asthma, and nasal polyps. The syndrome can be triggered not only by aspirin but also by NSAIDs. Strict avoidance of NSAIDs is the first line of therapy. Leukotriene modifiers are used to treat NSAID-induced asthma; these agents seem particularly effective and may become the mainstay of therapy. In those patients who absolutely need aspirin treatment, desensitization is another option to decrease disease activity.18 Consider nonselective beta-blockers as a potential cause of bronchospasm, especially in cardiac patients with asthma. Bronchospasm can also be precipitated by topical ophthalmic solutions that contain beta-blockers. Switching to an alternative agent is preferable, but if a beta-blocker is absolutely necessary, use a cardioselective agent.

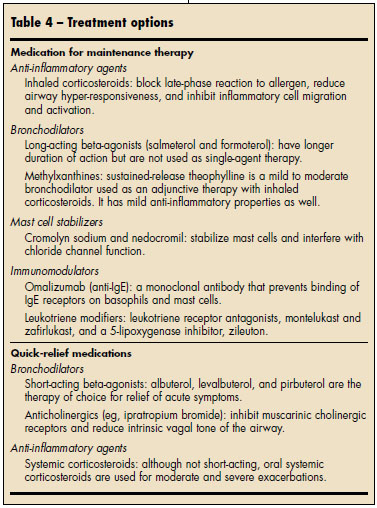

PHARMACOTHERAPY After a thorough workup (Table 3), what more can you do for patients who continue to have asthma symptoms, even though they are compliant with their inhaled corticosteroid regimen, have good technique, and have no alternative diagnoses or comorbid conditions? Such patients need additional medication to control their disease. The general approach to asthma has been to target airway inflammation and to relieve bronchoconstriction (Table 4).

Inhaled corticosteroids. These are the mainstay of asthma treatment. Increasing the dose of the inhaled corticosteroid may provide modest benefit. However, inhaled corticosteroids, especially at high doses, have been associated with growth retardation in children and with glaucoma, cataracts, skin bruising, and osteoporosis in adults. It may be preferable to achieve control by adding another agent and by keeping the corticosteroid dose low or moderate.

Long-acting beta-agonists. The EPR-3 guidelines suggest adding a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) to an inhaled corticosteroid regimen if greater control is required.5 The addition of a LABA ameliorates symptoms and improves lung function more effectively than an increase in the dose of the inhaled corticosteroid. 19 LABAs are particularly useful for controlling nighttime symptoms. These agents provide effective relief of asthma symptoms, although they do not address the underlying inflammation and are not recommended as monotherapy. A combination inhaler that delivers both a LABA and an inhaled corticosteroid in one device has theadditional benefit of simplicity and may improve compliance.

Recently, the FDA approved several newer combinations (Symbicort, Dulera) that provide prolonged bronchodilation and symptom control. Studies have suggested that LABA therapy can be dangerous and has been linked to worse outcomes, including asthma-related deaths. This has led to a series of FDA warnings about the use of these agents.20 However, many experts (including the authors) continue to find the use of LABAs in combination with inhaled corticosteroids to be safe and effective therapy when a patient’s asthma is not controlled on a low or medium corticosteroid dose alone. Long-acting anticholinergics. Recent data suggest that the use of long-acting anticholinergics has similar efficacy compared with adding a LABA to an inhaled corticosteroid and is superior to doubling the dose of the corticosteroid.21 This may provide an alternative approach in patients who cannot tolerate LABAs. These data, however, have not yet been incorporated into national guidelines or received FDA approval.

Leukotriene modifiers. They are not as potent an additive agent as LABAs, but they work in conjunction with inhaled corticosteroids to provide additional asthma control.22 In addition, leukotriene modifiers have the advantage of oral dosing, which is especially helpful for patients who have dif ficulty in using an MDI. They also are effective in patients with allergic rhinitis, which makes them an attractive option for those who have both allergic rhinitis and asthma.

Theophylline. It is now used only for add-on therapy because of its adverse effects (eg, tachycardia and numerous drug interactions). Use caution when prescribing theophylline, particularly in elderly patients who may have concomitant heart disease; be sure to monitor blood levels in such patients.

Systemic corticosteroids. Although systemic corticosteroids have a poor side-effect profile, some patients may fail to respond to any other therapy, particularly during acute exacerbations. When these agents must be used, taper the dosage as rapidly as possible. Watch for and counsel patients about adverse effects, which include glucose intolerance, cataracts, and osteoporosis. For those who are receiving longterm systemic corticosteroids, bone densitometry measurements at the start of therapy and 6 months later may be indicated.

Immunotherapy. The EPR-3 guidelines suggest consideration of immunotherapy for patients who continue to have severe asthma symptoms despite treatment with a multidrug regimen.5

Omalizumab. This is an alternative add-on agent for those patients with moderate to severe allergic asthma. 23 It is a monoclonal antibody that binds IgE and thus works early in the inflammatory cascade. Omalizumabreduces both symptoms and exacerbations, and studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of adding this drug to the regimen of patients who have poor control with combination LABA–inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Rare anaphylactic reactions have been associated with its use, and the drug should be administered by injection in a physician’s office.

FUTURE THERAPY

Newer combination therapies are expected to be introduced over the next few years. A number of noncor ticosteroid anti-inflammator y medications are being studied. New, more potent, once-daily LABA–inhaled corticosteroid combinations are in late stages of development as well.

1. Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma Prevalence, Health Care Use, and Mortality: United

States, 2005–2009. National Health Statistics Report: No. 32. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics. January 12, 2011.

2. DeFrances CJ, Lucas CA, Buie VC, Golosinskiy A. 2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey. National Health Statistics Reports: No. 5. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics. 2008.

3. Cherry DK, Hing E, Woodwell DA, Rechtsteiner EA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 Summary. National Health Statistics Reports: No. 3. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics. 2008.

4. Kamble S, Bharma M. Incremental direct expenditure of treating asthma in the United States. Journal of Asthma. 2009:46:1,73-80.

5. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. NIH Publication No. 07–4051. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. 2007. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2011.

6. Wechsler ME. Managing asthma in primary care: putting new guideline recommendations into context. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:707-717.

7. Castro M, Zimmermann NA, Crocker S, et al. Asthma intervention program prevents readmissions in high healthcare users. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1095-1099. Epub June 2003.

8. Gibson PG, Powell H, Coughlan J, et al. Limited (information only) patient education programs for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD001005.

9. Chrystyn H, Price D. Not all asthma inhalers are the same: factors to consider when prescribing an inhaler. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18:243-249.

10. Mazhar SHRA, Chrystyn H. Salbutamol relative lung and systemic bioavailability of large and small spacers. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:1609-1613.

11. Panettieri RA Jr, Spector SL, Tringale M, Mintz ML. Patients’ and primary care physicians’ beliefs about asthma control and risk. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009;30:519-528.

12. Holgate ST, Price D, Valovirta E. Asthma out of control? A structured review of recent patient surveys. BMC Pulm Med. 2006;6(suppl 1):S2.

13. Tovey E, Marks G. Methods and effectiveness of environmental control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:179-191.

14. Patterson PE, Harding SM. Gastroesophageal reflux disorders and asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:63-67.

15. Yigla M, Tov N, Solomonov A, Rubin AH, Harlev D. Difficult-to-control asthma and obstructive sleep apnea. J Asthma. 2003;40:865-871.

16. Corren J. The relationship between allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:35-37.

17. Stenius-Aarniala B, Poussa T, Kvarnstrom J, Gronlund EL, et al. Immediate and long term effects of weight reduction in obese people with asthma: randomized controlled study. BMJ. 2000;320(7238): 827-832. Erratum in: BMJ. 2000;320(7240):984.

18. Berges-Gimeno MP, Simon RA, Stevenson DD. Long-term treatment with aspirin desensitization in asthmatic patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111: 180-186.

19. Moore RH, Khan A, Dickey BF. Long-acting inhaled beta2-agonists in asthma therapy. Chest. 1998;113:1095-1108.

20. FDA Drug Safety Communication: New safety requirements for long-acting inhaled asthma medications called Long-Acting Beta-Agonists (LABAs); 2/15/2010. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsand-Providers/ucm200776.htm. Accessed April 4, 2011.

21. Peters SP, Kunselman SJ, Icitovic N, et al. Tiotropium bromide step-up therapy for adults with uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363: 1715-1726.

22. Lipworth BJ. Leukotriene-receptor antagonists. Lancet. 1999;353:57-62.

23. Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. Omalizumab, anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:184-190.